I may have written about West Campus a time or two before. But this time I come not to praise West Campus, but to bury it — in new developments! On Thursday, October 3, Austin’s City Council will consider the biggest changes to the rules that govern a good chunk of West Campus (known as UNO or the University Neighborhood Overlay) since they were initially passed in 2004. The proposed changes would:

Development

Economic Development without Tax Breaks

Economic development incentive deals — tax breaks to companies for bringing jobs to a city — have had a pretty bad run of news in Austin and beyond. Amazon’s HQ2 headquarters search earned a mile of negative attention for every inch of excitement even before they gave up on a deal with New York.

In Austin, economic development deals have been controversial for a while.

A Christmas wishlist for Austin’s next City Council

Austin’s new city council is shaping up to be the most development-friendly Council in recent memory. What kind of agenda could we expect or hope to see from the new City Council? Here’s what’s on my holiday wishlist.

Reform before Rewrite

CodeNEXT is dead. One reason it failed is that it combined two separate but related goals: increasing density and improving design. How dense different parts of Austin should be is a subject of intense debate. By contrast, the best ways to design Austin given a certain level of density is debated mostly by professionals. To the extent that the public debated design elements at all, the arguments sounded an awful lot like the only thing most people cared about is how these design elements affect yield. Looked at it this way, CodeNEXT was doomed to fail. It’s impossible to write coherent design guidelines when the public takes intense interest in them but evaluates them solely based on how much housing (or other buildings) they produce.

We must at least try to separate the issues of density and design. Improving the presentation of the code, the process of getting building permits, improving our streetscapes; all important issues that need a collaborative process informed by technical know-how. On the other hand, the question of whether we build a city that sprawls outward or soars upward is one with a lot of public input from the kinds of people who vote in municipal elections. It’s a question that has divided the electorate to the point of dividing communities like environmental groups and neighborhood associations. This is not an issue we can hope to just keep talking about until we find common principles. We don’t need to be nasty in how we debate the issue but we need to recognize that dumping these political questions on to staff and community engagement is doing more to cause rifts than heal them, without providing meaningful benefit. So, for my Christmas wishlist, I hope that our City Council takes a bold leap of faith and does the job they were elected to: settle political issues. That means making real movements on density even without the comfort of a completely undivided city. My real wish here is that come next Christmas, Austin can stop debating whether we are a place that welcomes new residents and start moving on to debating how we welcome new residents.

How could we do that? Here are some ideas:

Build up commercial streets

Austin has seen a number of new apartments (usually built on top of new shops or restaurants) on commercial streets like Burnet, Lamar (North and South), and South Congress since it first started allowing such buildings in 2004. They’re not my personal favorite housing style; I prefer to live on side streets with less traffic noise and pollution. But there’s no doubt that they’ve been a very popular type of new housing. They produce new homes for a lot of people who need them and they’re very easy to serve by transit, as streets with shops are already our most common bus routes. The new buildings are required to follow design guidelines that make the city more walkable, by doing things like limiting the number of driveways that interrupt sidewalks.

Here are three items on my wishlist to build on the VMU program’s success:

- Allow apartments on more streets. If a bus goes there, it should allow VMU.

- Allow apartments on all parcels on a street. Austin’s VMU ordinance made a political deal where it agreed to limit the program to certain parcels, which well-informed members of the public willing to sit through long meetings got to decide on. But that was 10 years and $1000/month in rent increases ago. It’s time to fill in the missing teeth and allow more properties to rebuild.

- Apply it to “Centers” as well as “Corridors.” This was an idea from the city of Austin comprehensive plan “Imagine Austin” that envisions a few more neighborhoods not dissimilar to West Campus with fewer undergraduates or Seattle’s Ballard (click through on the tweet to see the whole walking tour):

Self-guided walking tour of Ballard, one of Seattle's urban villages. Here's a conventional grocery store tucked under apartments, wrapped around parking. pic.twitter.com/dKEcyG6Acg

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) September 4, 2018

Allow more missing middle housing

“Missing middle” is the idea that there’s not a lot of ways to live in Austin that fall between a house surrounded by yard on all sides and an apartment complex with a leasing center with little bowls of candy in the waiting room. In other cities, you get lots of housing types in between: triple-deckers in Boston, greystones with up to 6 apartments in Chicago, or row houses in virtually every city the entire world over. Missing middle housing types can be employed on busy commercial streets; many cities have rowhouses interspersed with shops. But it really shines as a way of allowing more people to live on the calmer, quieter side streets where adults and children both are safer walking.

Redesigning Austin around missing middle housing is going to take a lot of work. We have effectively destroyed so much of our missing middle heritage that Austin’s Historic Preservation Officer proposed landmarking a fourplex as a rare example of a bygone housing type. But there are some items on my Christmas wishlist that are ready to ship today:

- Remove restrictions on subdividing buildings. If you’re allowed to build a mansion for one family to live in, you should be allowed to build that same mansion split into multiple apartments. This wouldn’t affect the health and safety regulations, nor would it affect regulations that affect the form of a house. It would simply take advantage of the fact that many of our houses are built too large and could accommodate more people with an extra stove and a wall between two sides of the building.

- Reduce minimum lot sizes. Austin requires unusually large amounts of land, measured in both area and width, in order to build a house or apartment building. Austin’s oldest and most beloved neighborhoods were built before that rule and have many lots with housing on smaller lots. Requiring so much land was a mistake and we should drop it sharply.

- Treat missing middle like houses not mega-complexes. Austin has a different set of rules for getting permits to build houses versus getting permits to build large buildings. While both types of buildings are required to follow zoning rules, large ones have to go much further in proving that they’re following the rules. This doesn’t have a huge effect on mega-complexes, which are always going to require complex permitting. But the additional paperwork can make it simpler to build an upscale mansion than a simple fourplex.

End Parking Requirements

Requiring that every house, apartment, store, school, daycare, and bar have its own parking places is crazy stupid. It encourages people to get an extra car even if they could get by without it, it adds crazy large expenses to everything we build, and it makes the city ugly as heck. Once you realize how much of a city is built the way it is just to provide huge amounts of parking, you’ll feel like you’ve just put on the goggles from They Live:

Parking requirements aren’t one of those “we just disagree on the right amount” ideas. They’re always wrong and the best thing we can do is eliminate them entirely. But if that isn’t on the shelf at the mall, some good alternatives could be:

- Eliminate parking requirements near buses and trains.

- Eliminate parking requirements in special districts like TODs and West Campus.

Expand Downtown and West Campus

The downtown/UT campus area is a special place, different from any other part of Austin and in some ways any other part of Texas. Austin has one of the largest percentages of jobs in its central business district, understood in this case to extend all the way up to UT. Although this can cause problems with car traffic when many people commute in from around the city surrounded by their steel cages, it’s a huge advantage for running transit. These areas are both doing very well but threatening to run out of room as they get built up. So what would I love to get to fix this?

- Rezone more of downtown to CBD or DMU, the two zoning districts special to downtown.

- Expand West Campus’ special zoning to more parts of West Campus.

- Expand the “inner West Campus” zoning district that allows taller buildings to more of West Campus.

Start working on Comprehensive Zoning

Design and density go best together. A comprehensive rewrite of our land development code could be far easier to achieve once the Council has set the policy direction clearly. But no matter what, it’s going to be a long process. When CodeNEXT died, many people from within the development and homebuilding industries actually let out a sigh of relief as they felt many of the areas outside the public interest weren’t well-enough examined. Outside of the pressure cooker of setting the city’s direction on density, real progress can be made on the more technical aspects of the code. Let’s start.

How West 6th Was Accidentally Fixed for the Age of Scooters (and How to Keep it Fixed)

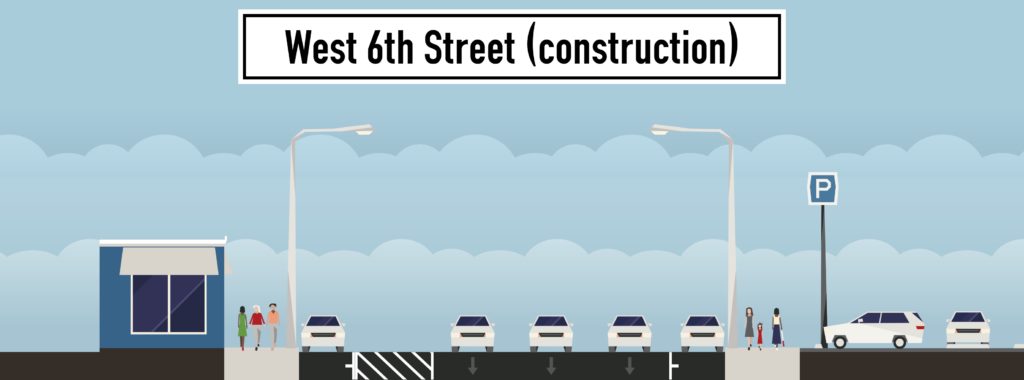

There’s a new development on West 6th Street downtown. A six-story hotel going by the name “Canopy By Hilton” is being built next to Star Bar, between Nueces and Rio Grande (details at Towers). Space being rather constrained next to the hotel site, the developers have rented space to stage demolition and construction on the street itself, temporarily narrowing 6th Street:

For the last week, West 6th St has been narrowed between San Antonio and Rio Grande to make room for construction of a hotel. As a result, the street feels much safer. @austinmobility, let's make it permanent. pic.twitter.com/Tllk7FzzAQ

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) September 18, 2018

Here’s what 6th Street looked like pre-construction from the perspective of the Google Maps street view car:

Let’s take that and simplify it a little in StreetMix:

Now, let’s look at what it looks like today:

Let’s simplify that in StreetMix again:

A funny thing happened on my walk home recently. I noticed that there were no cars parked in the parking spots on the left hand side of this picture and a number of people were using it to scoot in. The blocked-off lane was functioning as a buffer between the scooters and car traffic, thus creating a temporary protected lane.

If the city kept this configuration but made it slightly more permanent, here’s what it might look like in StreetMix:

I’ve replaced the car parking on the left with a two-way bike/scooter lane and updated the buffer so that people can use it to park scooters. Also, I threw in some potted plants as buffers to discourage people from using the buffer, by accident or impatience. The buffered area could not only fit scooter and bike parking, but it could do so and still leave room for a few taxi/Lyft pullouts. Is this the ideal configuration of West 6th? No; I definitely think a professional street designer could do better. But it shows how even a very low-dollar intervention could simultaneously remove some of the many annoying and at times dangerous conflicts on downtown streets:

- Conflicts between people riding scooters and people driving cars

- Conflicts between people riding scooters and people walking on sidewalks

- Conflicts between people parking scooters and people walking on sidewalks

- Conflicts between people getting picked up or dropped off in Uber/Lyft cars and people driving cars, scooters, or bikes.

Of course, just because this configuration wouldn’t cost much money to execute, it doesn’t mean there aren’t non-financial costs:

- 13 meter spaces are removed from the street, forcing more drivers to pay market rates to park their cars in parking lots or garages.

- One car-sized lane has been removed from the street, reducing the peak capacity and slowing the time it takes for drivers to get from downtown to Mopac at rush hour.

Conveniently, Austin has more parking downtown than it has land downtown. (This is true because parking spaces are largely stacked on top of one another).

The amount of parking in Downtown Austin is equal to one surface lot larger than Edwin Waller's original city plan. pic.twitter.com/1HE8bbCcTy

— Caleb Alan Pritchardo (@cubbie9000) May 14, 2018

So, the question becomes not one of finance but one of values and vision. Are we a city that values safe, convenient streets for walking, biking, and scooting, as well as driving, or are we a city that can’t wait the additional two minutes to get on Mopac?

Opportunity Kicks

The hottest political topic in Austin right now is a proposal by the owner of the Major League Soccer franchise Columbus Crew to lease space on a city-owned parcel in North Austin. To see the more colorful side of the debate, browse the #MLS2ATX or #SavetheCrew hashtags on twitter:

Just a regular #CrewSC tailgate. #SaveTheCrew pic.twitter.com/JcGJHv6Vld

— David Miller (@DavidMiller0789) August 11, 2018

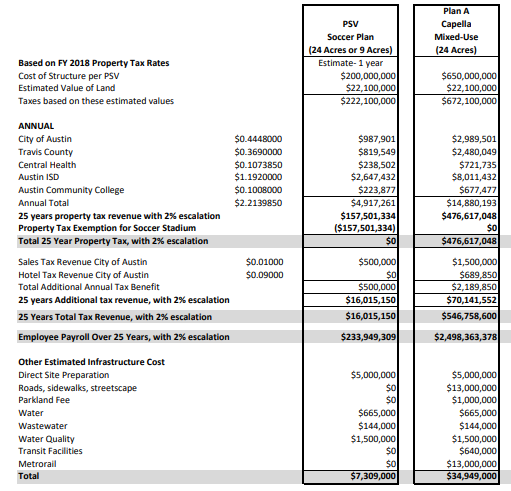

I’m not going to rehash the debate, but rather pick out one piece of the “no” side’s argument, led most strongly by CM Leslie Pool: the opportunity cost of leasing the parcel for a stadium. While the lease would be a financial positive for the city compared to doing nothing on the land, that isn’t the only other option. A nearby property owner/developer, for example, has proposed an alternative plan where they buy the land, build a relatively dense mixed-use development, and pay taxes annually estimated at $15m per year. The “opportunity cost” argument is a really good argument. In fact, this argument is so good that I’ve made it a few times myself over things like the immense value to the city of new construction in West Campus, or the potential opportunity cost of a tax-free convention center annex. (Proud that the proposal I successfully passed in the Visitor Impact Task Force recommended a future convention center annex remain taxable.) In fact, this is such a great argument that I desperately, desperately wish people used it more often. In a previous policy decision, the decision on what a Planned Unit Development agreement would look like for “the Grove,” a plot of land off 45th Street near Mopac, one of the leading opponents of a similar sort of dense mixed-use development was the very same CM Pool and I don’t recall her carefully weighing the benefits of limiting residences there against the tax revenue the city would forego by allowing more construction.

But the point isn’t to discredit the argument by calling hypocrisy. The argument is really good! It’s an argument worth making! While large developments like the Convention Center annex, McKalla Place, or the Grove are relatively visible because they’re covered in local media and debated by City Council, virtually every land use decision that the city makes has a fiscal dimension, yet we rarely ever think about it. (To his credit, Council Member Flannigan frequently invokes the fiscal impacts of development patterns.)

So, let’s talk about fiscal impacts!

Rule 1: Compact development tends to be more valuable

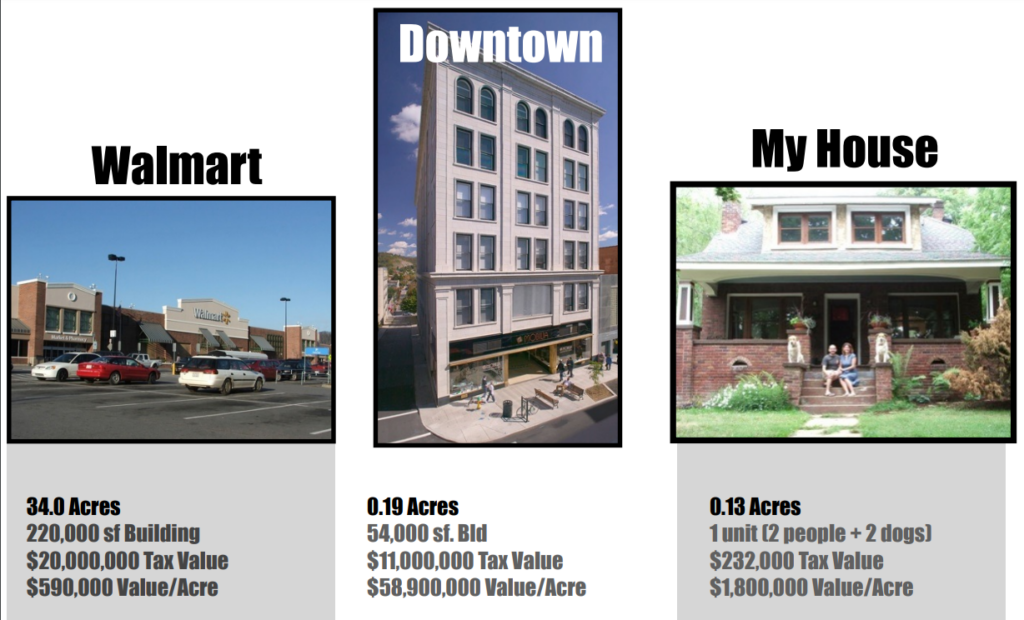

In a fantastic presentation prepared for the Downtown Austin Alliance, consultant Joe Minicozzi compared the fiscal returns to a city from different kinds of development:

While a Walmart may have eye-popping tax values because it’s such a large single development compared to a traditional low-rise office building or house, a low-rise office building also requires much less space to deliver value. Many of a city’s costs, like building streets, scale by the linear mile not by the person. It costs much much more for a city to provide services to a Walmart than to a downtown city block. For residential buildings, the same rules apply. If a city has 5,000 residents, it’s easier to provide them services if they live in a single cluster of 250 acres than if they spread out to 4,000 acres. In Austin, we see these expenses in items like the five fire stations the fire department has requested to cut down response times on the outskirts of the city. I don’t begrudge people who live on the outskirts fire stations. But I do wish we had denser land development patterns in the central city to better take advantage of our existing fire stations and roads.

Rule 2: Value is driven by making great places for the long term

Take a look at the Capella proposal again. In addition to the $15m in annual tax revenues, they will pay other costs: for example, $1m in parkland dedication fees. Additionally, they have offered $22m for the purchase of the land. These types of one-time fees, both voluntary and required, typically dominate policy discussions but they are drops in the bucket compared to the long-term tax revenue from building a great place that could last a century or longer. The financial life-blood of a city is not in one-time fees but recurring taxes levied every year on great places for its residents to live, work, and enjoy themselves.

When a city considers the fiscal impact of a development, the question it should be asking itself is not how much can we extract from this developer today but: is this developer making a place that 50 years from now people will still want to be in and still be willing to pay taxes on? The Littlefield and Scarbrough Buildings, two modest 8-story downtown Austin office buildings that were anything but modest at construction time pay close to $1.4m in taxes year-in and year-out more than 100 years after they were built, after their historic building tax breaks!

Rule 3: Taxes are only one of many benefits to consider

Of course, not all of life can be boiled down to profit and loss, tax revenues and maintenance costs. Parks cost taxes to maintain and don’t directly raise taxes themselves, yet most of us love them. Comparing the often difficult-to-quantify benefits with the easy-to-quantify costs can be difficult and frustrating, as both CM Pool and CM Flannigan express here:

👀 #atxcouncil pic.twitter.com/tb91veWJZO

— Nina Hernandez (@neenthirteen) August 11, 2018

There’s no obvious right decision on a given question. Is it worth it to Austin to pay millions of dollars in maintenance and forego even more than that in taxes for things like the Butler Hike and Bike Trail, Zilker Park, or Barton Springs? The overwhelming majority of Austinites would say yes. Is it worth it to Austin to forego millions of dollars in taxes to “bring people together” through a soccer stadium or to prevent dense development on the former TxDOT site? Could it be worth it to create another West Campus, throwing off tens of millions in tax revenue annually to fund things like parks and schools and soccer fields? Austinites are much more split on these questions and that’s why they’re political decisions. But if we want to make good choices, we need to understand the costs and benefits clearly.

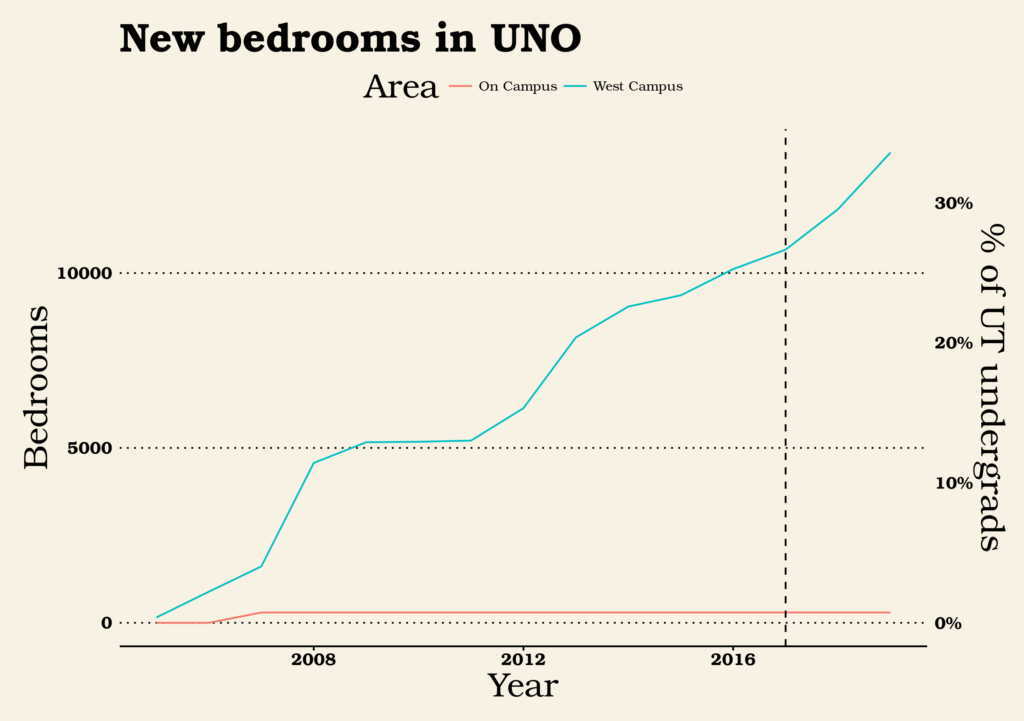

West Campus’ remarkable growth, charted

This blog has something of an obsession with West Campus. It’s the neighborhood that lives by upside-down, inside-out rules and it’s a window into the Austin that could be. So when we got a hold of data about West Campus’ growth, we pretty much had no choice but to put it in charts.

Part 1: Understanding the scale and speed of West Campus’ growth

West Campus has grown fast

Since the creation of the University Neighborhood Overlay in 2004, there has been a pretty steady growth of new homes with a brief financial-crisis-induced break in 2009-2010. The numbers are really quite stupendous: over the course of a decade, essentially a new town of 10K people has been added to what was already one of Austin’s denser neighborhoods.

In this chart, I show two equivalent axes: bedrooms (on the left) or % of UT undergrads those bedrooms represent (on the right). I chose to use bedrooms rather than units because of my intuition that student housing is typically occupied by one person per bedroom, so a 4-bedroom unit really does house twice as many people as a 2-bedroom unit. (In other housing, a 4-bedroom unit may mean that one or more bedrooms are being used as a study or guest room.) The blue line shows the number of new bedrooms created in the UNO overlay, while the red line hugging the bottom shows the number of new bedrooms created by new dorms on the UT campus itself. Numbers after 2017 are projections based on city filings rather than completed units on the ground. At the rate UNO is growing, approximately half of UT undergrads will live in new units created under UNO by 2023.

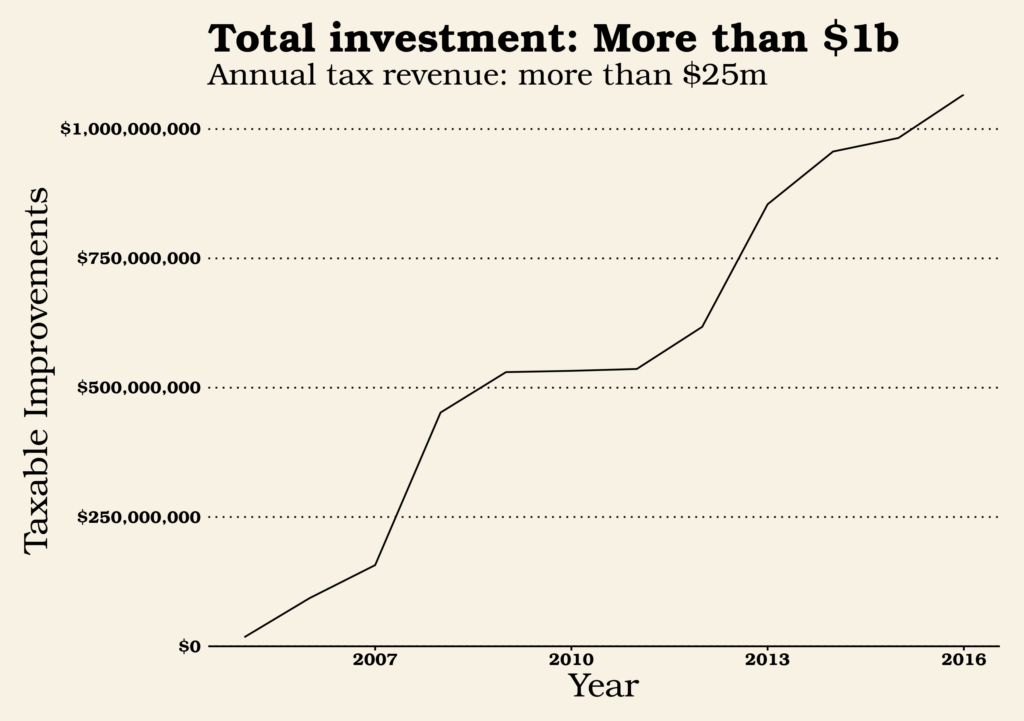

A lot of investment

How much does it cost to build out a neighborhood? Using 2017 tax valuation, the UNO buildings alone (not counting the land they sit on) were valued at a bit more than a billion dollars. For comparison, Austin’s last affordable housing bond was for $65m and the capital costs of Austin’s proposed 2014 light rail bond was about $1.5 billion. Each year, the buildings in UNO contribute more than $25m in property tax revenues to the various local government taxing entities: the city of Austin, Travis County, Austin Independent School District, Austin Community College, and Central Health.

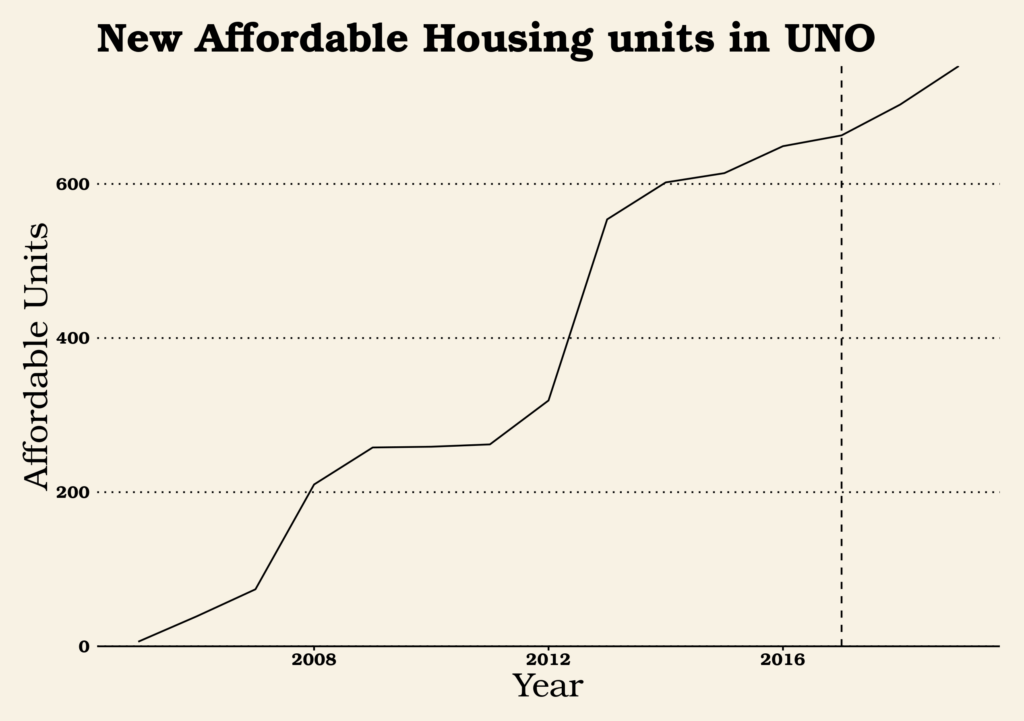

A lot of new income-restricted apartments

West Campus is home to one of the largest concentration of developments in Austin with apartments specifically for people below certain income levels. There are two reasons for this: 1) as part of the new rules for building apartments, developers are required to set aside a certain number of units for eligible people, and 2) there has been a lot of development in West Campus.

Part 2: How UNO has changed over time

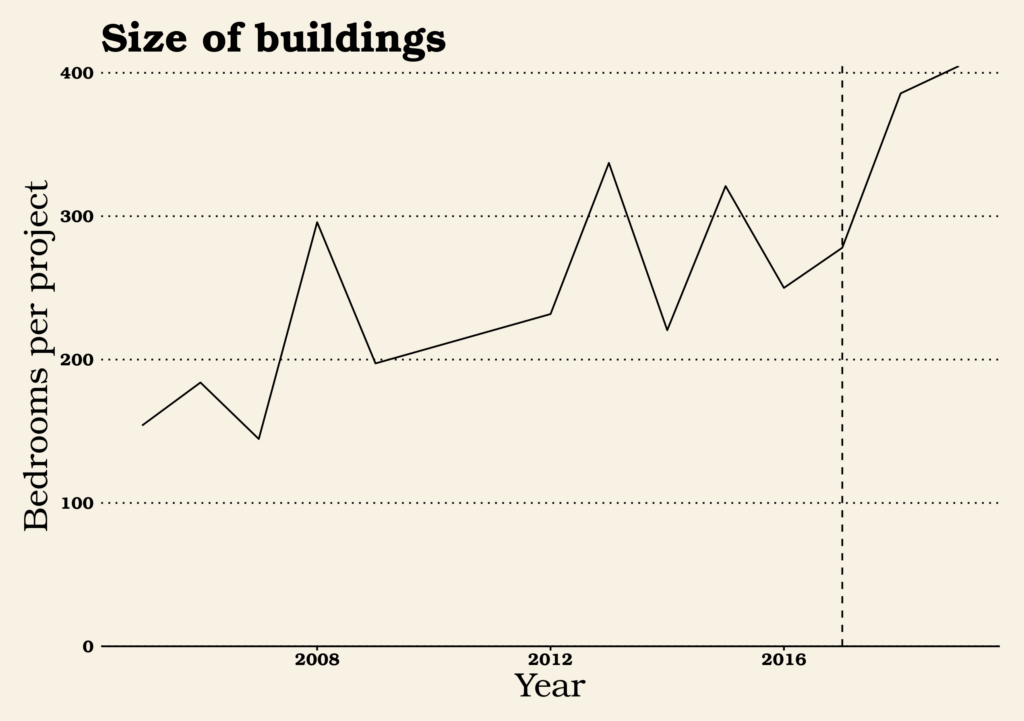

Buildings are getting bigger

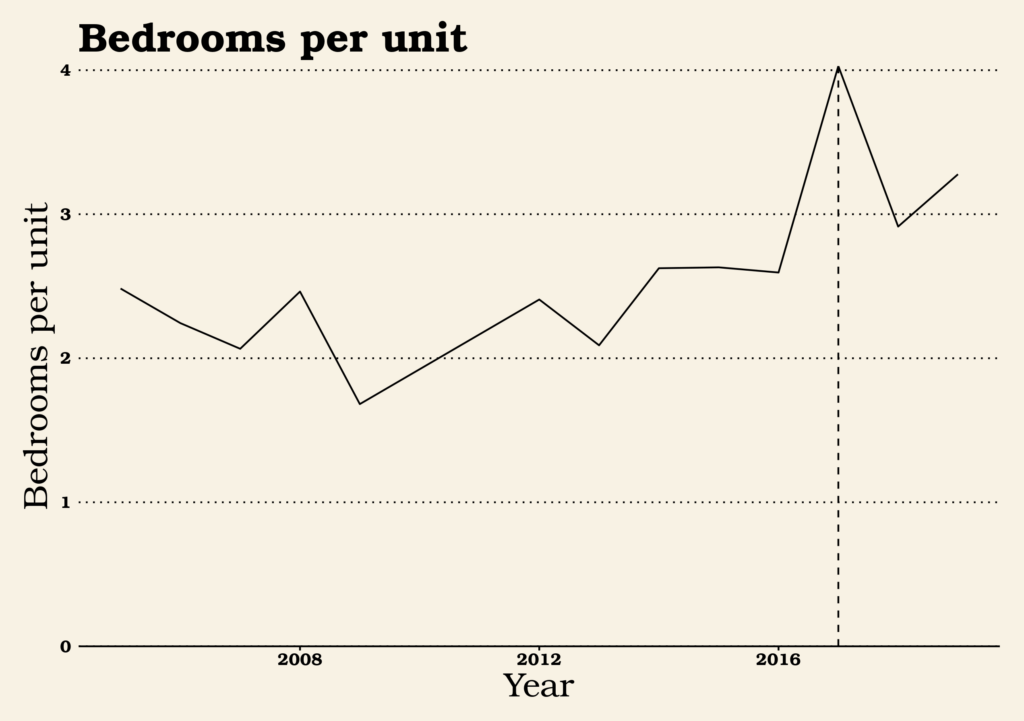

Buildings are getting bigger overall, as expressed by number of bedrooms per project. I’m not sure why this would be; perhaps easier-to-finance mid-rise buildings have proven the way for larger high-rise projects. Perhaps the most easy-to-build sites were in the lower height districts and investors are moving on to the more difficult-to-build sites in high-rise districts.

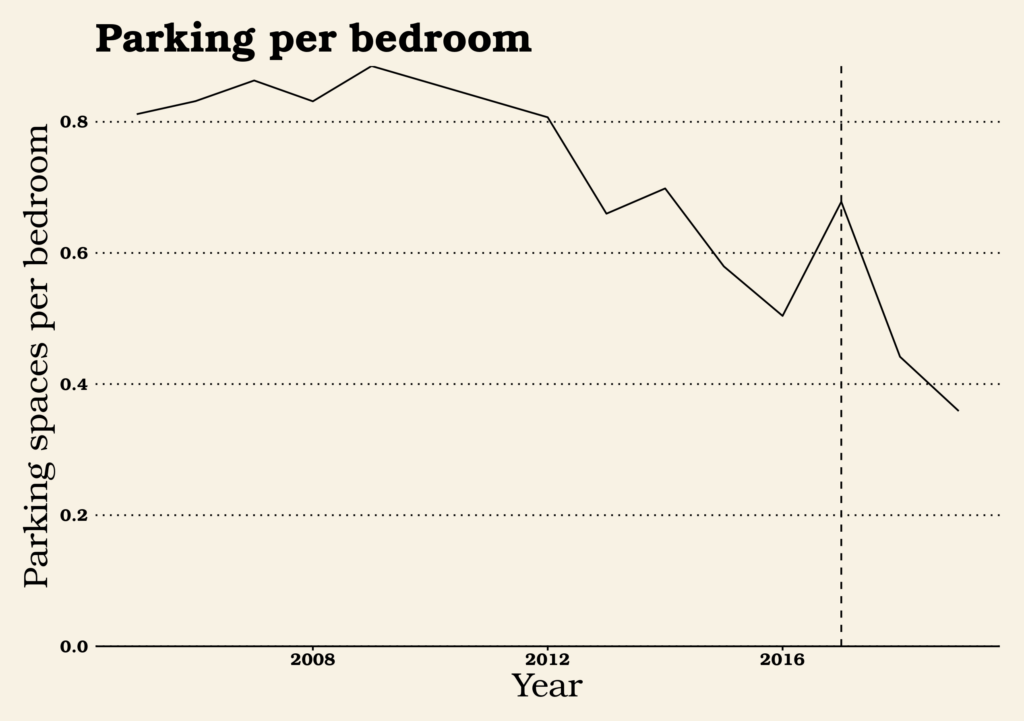

Parking by bedroom

Over time, the number of parking units added per new bedroom built has dropped precipitously from a high of nearly 0.9 parking spaces per bedroom to 0.5 in 2016 and an anticipated 0.36 in 2019. Apparently, when we build places near other places, more people can get around without a car. There’s a number of ways these change might be explained:

- Developers and financiers have become more comfortable with building less parking as earlier buildings saw less parking used than anticipated.

- As more commercial amenities have moved into the neighborhood like the Fresh Plus grocery store, fewer students have needed cars.

- Younger people more generally have lower preferences for having cars with them at school than they used to.

- Developers have gotten better at managing city rules to find ways to avoid expensive required parking. (More on this later.)

Bedrooms per Unit

The number of bedrooms provided per unit is a major way that West Campus departs ways from the rest of Austin. Developers typically build studios and 1-bedroom apartments to accommodate the many 1- and 2-person households the city is adding. In West Campus, developers have always built more bedrooms per unit, probably because students are more willing to share a suite with unrelated roommates than many non-students. Of late, though, the number of bedrooms per unit is going even higher. Why? I have a hunch.

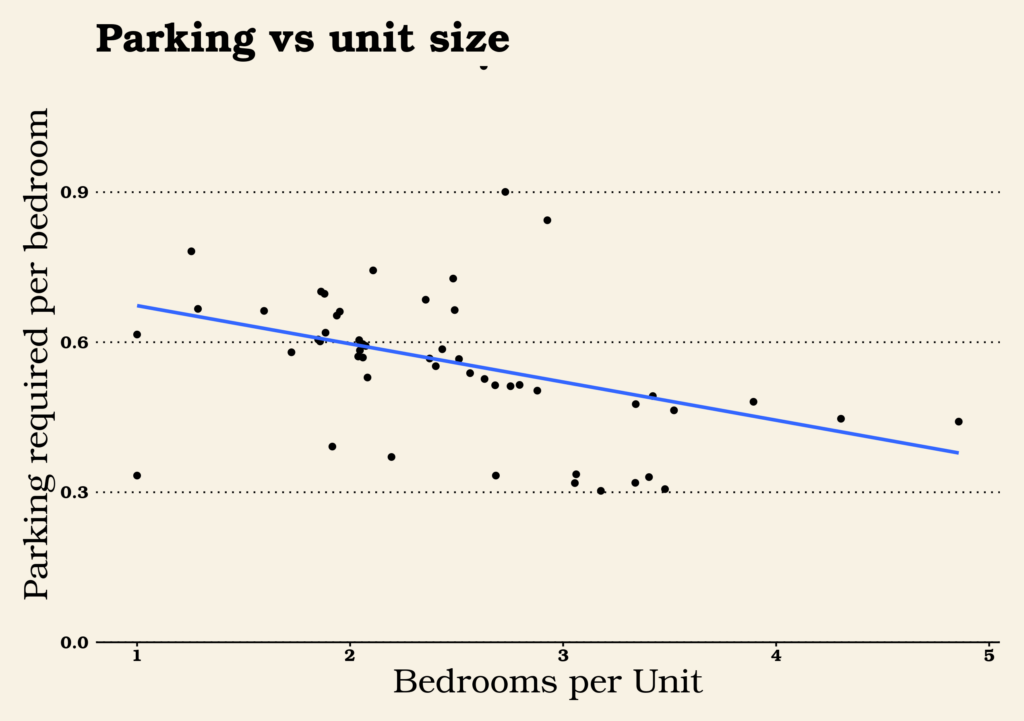

Parking by Unit Size

This is a trickier chart than the others. On the bottom axis, there’s bedrooms per unit. On the left axis, there’s parking spaces required (not built) per bedroom. The dots and the blue trend line both show that, generally speaking, the more bedrooms provided per unit, the fewer parking spaces a developer is required to build.

Based on the trend toward less parking per bedroom and more bedrooms per unit, my hunch is that developers have figured out that parking is not an amenity that enough students want or are willing to pay for to justify the fairly high costs of building it. So now they’re trying everything they can to avoid the expense of building unwanted parking garages, including build bigger suites for which they aren’t required to provide as much parking. If this is true, it’s another example of a remarkable property of zoning codes: they always have unintended consequences. Zoning code didn’t set out to decide how many college students should group together into a suite, but it might well have decided it nonetheless.

[Edit: A dissenting view comes in from friend-of-the-blog Tyler Stowell. See below.]

Conclusions

This has been a fun romp through a little dataset. Let’s reiterate some of the conclusions I’ve drawn:

West Campus shows little signs of slowing down

There are sometimes worries that when a part of town allows denser housing, there will be a big bang as all the most likely sites get developed and the ones that remain all have special problems. If that’s the case with West Campus no effects are obvious. New sites come on to the market all the time and there are still surface parking lots or low-rise buildings that are prime targets for redevelopment. We could well see new West Campus buildings account for 50% or more of the undergrad population before long.

The city still requires too much parking

The trend we observed toward fewer and fewer parking spaces being built — and especially the trend toward weighting the unit mix toward parking-light high-bedroom units — tells me that developers are seeing little use and little market for their parking. With Bcycle rideshare taking off on top of the existing walking, biking, and bus routes, most students in West Campus just don’t want or need cars. Eliminating parking minimums would also allow developers to be more creative in other areas, providing different amenities or lower costs.

The city regulates way more private investment than it makes public investment

So far, rebuilding West Campus has been a $1B project, far dwarfing the amount of money the city has spent directly or indirectly on housing development. Most of the time, we don’t think of it as a single “project” because there is no one single coordinating entity controlling what buildings get built in what order. But it was created as a result of a city policy change. Even the smallest changes to city policy, in this case only affecting a single neighborhood, can end up affecting far more private investment than direct municipal spending affects.

[Note from friend-of-the-blog Tyler Stowell:] I’d disagree with one of your points though – my observation is that the higher bed/unit ratio isn’t a way around parking requirements, it’s a cost cutting measure. Bedrooms are cheap and pay rent. Kitchens and bathrooms are expensive and don’t pay rent. Diluting the cost of kitchens/baths over more beds equals higher profit for the developer. And this works in west campus for college students who might’ve lived in Jester last year. Not so much in other markets. The parking is always a target percentage of bedrooms and truly is market driven (eg. my last project the developer wanted to provide a space for 80% of bedrooms). Some projects take the full reduction allowed by UNO, but some go higher.

Contest: What’s your Congress Ave like?

We have a contest for you! With prizes including a $25 gift certificate generously donated by Pop Bar, offering ice cream bars at 247 W 3rd Street downtown starting Friday January 26th. Read to the bottom for details on how to enter!

One of the great forces in shaping Downtown Austin is its capitol view corridors. As we speak, downtown Austin is being made over in their image, with Austin’s signature architectural feature becoming the corner-cut tower. Capitol view corridors are a relatively recent phenomenon, passed into law in 1983 on the initiative of then-Texas State Senator Lloyd Doggett. But the granddaddy capitol view of them all, the terminating vista along Congress Ave, has been baked into Austin’s DNA since 1839 when Judge Edwin Waller laid out the street grid of the Republic of Texas’ brand new capital city. Congress Ave has undergone many changes through the years. James Rambin did a fantastic rundown on those changes at sister site Towers.net, so I’ll just do a quick picture recap here.

Here is Congress Ave in the 1880s (via KUT), when Austin had no cars except mule-pulled streetcars.

By 1913, the street had been paved and the streetcar electrified, but streetcars, carriages, and pedestrians still ruled the day:

By the 1930s, the personal automobile had overtaken streetcars and carriages as the dominant use of the Avenue.

A 1976 proposal that never got adopted included a vision for a Texas makeover of Congress Ave intersections. The last major shakeup to actually happen was in 2014, when Cap Metro’s bus network shifted its major downtown spine off Congress Ave to Guadalupe and Lavaca Streets. But there may be a new shakeup coming soon! The city of Austin has undertaken an initiative to redesign Congress Ave and has already begun the process of testing out ideas.

Well, recently I took a trip to Mexico City, where I stayed on Avenue Mazatlan in the Condesa neighborhood, a street the same width as Congress Avenue, but configured entirely differently, with a tree-lined pedestrian/bicycle/dog/rollerblade shared-use path running down the center of the street (top two pictures in the first tweet):

[tweet 951979446743027712 hide_thread=’true’]

[tweet 952584067907645441 hide_thread=’true’]

This inspired to me to get out the Streetmix tool and put together a vision for how Congress Ave could look with an emphasis on giving people access to the terminal vista of the Capitol while walking or on their bikes:

How would you feel about being able to take a stroll along Texas' most iconic terminal vista? pic.twitter.com/HLN4sCh78j

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) January 20, 2018

Other twitter users have imagined alternative visions:

I'd like it better if they'd cut out the north/south lanes except for bikes and only leave the cross streets a la Lincoln Road on Miami Beach.

— Victoria Garza (@victoriagarza) January 21, 2018

[tweet 954894923853193216 hide_thread=’true’]

So, Austin on Your Feet and Towers.net have decided to give everybody a chance to design their own version of Congress Avenue and vote for their favorites. You can remix my Streetmix or start your own. The rules are: submit a design from streetmix by tweeting with the hashtag #CongressTowers by February 8 or emailing to contest@austinonyourfeet.com. The street must be exactly 120′ wide. We will select the best entrants and give readers a chance to vote for their favorite alternative. The entrant with the most votes will receive a $25 gift certificate to Pop Bar and Towers.net sunglasses. So get out there and get designing!

6 things to like in California’s proposed transit housing law, illustrated by surfing

On January 4, California felt two earthquakes. The first was a conventional and thankfully weak earthquake in Berkeley:

The Did You Feel It? survey form for the Berkeley, CA M4.4 EQ is back up and running: https://t.co/jY2poBayEX Please tell us what you felt. pic.twitter.com/OVb8r4p22q

— USGS (@USGS) January 4, 2018

The second was a political earthquake, emanating from across the bay in San Francisco:

I’m introducing an aggressive housing legislative package: 1) require denser/taller zoning near public transit, 2) require cities’ housing goals be based on actual future growth & make up for past deficits, & 3) make it easier to build farmworker housing. https://t.co/YLQ9djH5pN

— Senator Scott Wiener (@Scott_Wiener) January 4, 2018

So, here are six things to like about the transit-oriented development bill that’s making waves in state politics:

1 It acknowledges the state has an interest in land use

Many decisions are better made by cities than states. Where will the next branch library go? Should this park have a splash pad or a lawn? But some problems are too big for one city alone, like intercity transportation. If Austin and San Antonio decide to be connected by a train, Buda, Kyle, San Marcos, or New Braunfels should have input (as the train would go through these cities), but they shouldn’t be given a flat veto. It is up to the state government to help manage this process so that local interests in one city don’t hurt local interests everywhere else.

In California and some other states, housing and land use have become problems with statewide and national implications. Housing prices aren’t just high in San Francisco or Los Angeles or even Berkeley; people unable to find housing in those cities are spilling over to suburbs and exurbs all across the state. Whole companies are looking to other states to set up offices because their workers can’t afford California rents. The greenhouse gases from long commutes affect every person on the planet. When a problem is widespread, the solution needs to be widespread too; cities rules by local interests just doesn’t cut it.

2 It creates fair and impartial rules

Laws made at the local level can take into account local context better than statewide rules can be. But laws made at the state level can better take into account the statewide context. In a drought, we need fair rules so that everybody does their part to conserve water and everybody has access to the water they need. In a statewide housing drought, we need fair rules so that everybody does their part to build housing.

3 It forges a link between transit and density

In the sphere of YIMBY and placemaking, the problem in California is a very YIMBYish problem: there aren’t enough homes to go around for all the people who want to live in California’s cities. But the solution that Wiener proposes isn’t just focused on getting people into homes anywhere. By proposing rules for allowing more homes near transit, it creates the chance for cities to use this as an opportunity to make great places for the future, where high-capacity transportation solutions are matched with high-capacity housing solutions.

4 It acknowledges how parking rules can hurt housing

One type of land use rule that’s particularly pernicious is the minimum parking regulation. These rules not only incentivize car use by forcing everybody to pay the price of car storage whether they drive or not, they also cut into the budget (both financially and physically) of new housing. This legislation will stop cities from using these pernicious rules near transit stops and opens the possibility for people to find new ways to live cheaper while using less parking.

5 It helps bridge the gap between people and jobs

The problems of California’s cities aren’t their problems alone. Vast swathes of the state are home to unique industries, from Silicon Valley’s tech economy to Hollywood’s movie industry. Sure, tech jobs exists outside Silicon Valley and movies are filmed all over the world. But place has, if anything, grown more important over the last decades, not less. Young workers looking to break into an industry would do well to show up where the jobs are, and new companies looking to start up would do well to show up where the workers are. Today, though, many people are shut out of these engines of prosperity because they can’t afford to live in Palo Alto, San Francisco, or Los Angeles while they lean the trade. Who knows what great technology or film talent we may cherish tomorrow if only we make room for them today?

6 It might just save humanity

With the United States federal government oriented away from action against climate change, individual states badly need to step up their game. While trying not to overstate the importance of this bill, the fate of the entire human race might depends on our ability to transition the United States and our high-emission society into one in which we can get around more efficiently.

So congratulations to Senator Scott Wiener! You brought a proposal that deals with the scale of the problems your state and this country are experiencing, and you may have changed the conversation on housing for good.

Words by Dan Keshet. Gif selection by Susan Somers.

The one little rule that decides where Austin’s towers build parking

Not every tower in downtown Austin looks exactly the same, but there is one defining characteristic that describes almost all of them: parking. Most towers rest on top of what they call in the industry a parking plinth, the tower base where folks store their cars. (Plinth is a Swedish word meaning ugly thing.) Here’s a typical example, the Seaholm Tower in southwest downtown.

On the ground floor, there’s a restaurant. Above that, the area with small and sporadic windows is the parking garage. Above that, the area with balconies is where the condos live. Simple, effective, but not always super sightly, at least to my tastes. Why not build parking underground, freeing up aboveground levels for more homes? For one thing, building underground car parking is very expensive. The exact difference varies by site but I’ve seen estimates that moving a parking space underground can add $10K to the cost of the space — and the further you have to dig, the more expensive it gets. So perhaps underground parking is reserved for the most expensive buildings?

No, even in Austin’s newest luxury towers you see aboveground parking:

Parking underground is just too expensive for Austin, or so I thought, until Sid Kapur pointed out to me that there is somewhere in Austin building underground parking:

[tweet 938849429121060865]

Yes, of course, West Campus (aka Bizarro Austin) is building underground parking. See James Rambin’s writeup at sister site Austin Towers of projects like Skyloft and Aspen West Campus with four stories of underground parking. So why do developers building student housing decide to put parking underground? Are students more discerning aesthetic connoisseurs? Sorry, students, but I doubt it. I have an alternate theory.

There are many different ways that zoning codes can limit the amount of space that can be built. In downtown, the binding constraint preventing even larger buildings is something called Floor Area Ratio or FAR: roughly, the square footage of climate-controlled space in a building divided by its footprint. In West Campus, the binding constraint on the size of a building is regulations on maximum height. Crucially, parking counts toward a building’s height but doesn’t count toward its FAR. If a developer in West Campus moved their parking from below-ground to above-ground, they would have to remove apartments in order to fit it in, costing them a lot of money in lost rent. Developers downtown, though, don’t have a height limit so building a parking plinth costs less than putting parking underground, doesn’t use up the building’s FAR, and even makes the residential units more valuable by giving them better views.

If my theory is true, it makes some predictions: portions of northern downtown that are slated to be rezoned with height-constrained zoning categories (CC-40 and CC-60) will likely see underground parking, while the FAR-constrained central business district will continue to see parking plinths. Indeed, the condo building I live in downtown was built pre-CodeNEXT but it had height limits imposed as part of the rezoning process and consequently built most of its parking underground:

Convention Center Bombshell

Previously, I have been skeptical of a convention center expansion. As a member of the Visitor Impact Task Force, I came around to a positive recommendation after the Task Force recommended ways to make expansion a positive for the city:

- Incorporating expansion as part of a larger tower to share costs and add activity when the convention center isn’t being used.

- Keeping the convention center expansion on the tax base.

- Keeping the street grid, the long-term source of value in the downtown district.

For background on the convention center and its surrounding environment, check out coverage from TOWERS.

On August 29, city of Austin staff casually dropped a bombshell that gives the possibility of multiplying these benefits many times over: building a Convention Center expansion may open the possibility of redeveloping the existing Convention Center. The possibility seems remote but it would be an enormous development so let’s step through it.

What is there to gain from redeveloping the area?

The Frost Bank Tower paid $7.5M in property taxes in 2017. Expanding that out to the Convention Center’s six blocks, that’s about $45m in potential tax revenue from the Convention Center’s 6 blocks! That’s almost as much as the city spends on the repaying Convention Center construction loans and operations put together!

These taxes represent the real benefits to Austinites that onsite towers could provide: homes, workplaces, shops, restaurants, etc. Today, way more people wish they could live downtown than live there, as evidenced by the record prices people are paying for downtown condos and apartments. Building more offices and homes will allow more of the people who want to live and/or work downtown to do so. According to the staff presentation, there could be up to 4 million square feet of buildable space there. That could be enough housing for 4,000 households, enough office space for 20,000 jobs, or some combination thereof.

Lastly, the convention center doesn’t just occupy land that could be used for other purposes, but it also occupies the streets and sidewalks that people would otherwise use to get around. Returning that land to be used as streets would make it easier for people to get around, making all of the land around it more valuable. For example, the City of Austin and Waller Creek Conservancy are currently investing large resources in renovating Palm Park on 3rd Street, but few people downtown use that park in part because it’s hard to get to! It may even provide traffic relief by providing alternative means to get to destinations on opposite sides of the convention center.

Why does redeveloping the Convention Center depend on expansion?

Designing a vertical convention center is difficult; one of the most important aspects of convention center space is beam-free space ― enormous wide-open rooms without any vertical supports to obstruct views. Designing spaces to be beam-free is difficult as part of larger tower structures which require vertical supports. Convention centers are not generally built vertically for this reason and the Austin Convention Center was definitely not built with vertical expansion in mind.

Without expansion, redeveloping the convention center for more square footage in place would entail years of foregoing hosting large conventions in Austin. While Austin is a hot convention market today, taking such a dramatic step would risk crippling the future convention industry in Austin. Skills and connections would rust as convention bookers would lose touch with Austin, convention center staff find other jobs, and convention-oriented businesses like the JW Marriott or Fairmont Hotel would need to reorient.

The Convention Center redeveloping could therefore only be approached out of strength or serious weakness: with the strength of new modern facilities in place to accept conventions or the weakness of a rapid decline in Convention Center fortunes forcing a desperation move. We are nowhere near the latter―Austin has been moving up the ranks, not down the ranks, as a Convention destination.

What are the next steps?

The possibility of a redevelopment of the existing Convention Center changes the ideas for expansion dramatically. While the expansion has focused more on meeting space and ballrooms, if it is to serve as an interim or permanent replacement for some or all of the existing Convention Center, it would necessarily include more exhibit space and an area for trucks to unload into it. For the city, therefore, the next step would be to include information about potential for redevelopment of the existing Convention Center in any Request for Proposals it releases.

For the Austin urban design and architectural communities, the next step is to develop ideas and visions that can inspire stakeholders and the whole city to believe that a megaproject like this could make sense for the Convention Center, for other downtown business, for transportation, and for the city and its finances. So architects, designers, placemakers, enthusiasts: do you have thoughts about how this could happen? A phased approach to redeveloping the southeastern corner of downtown? Please send them to dan@austinonyourfeet@gmail.com and let me know if I can share them with my readers!