This blog has something of an obsession with West Campus. It’s the neighborhood that lives by upside-down, inside-out rules and it’s a window into the Austin that could be. So when we got a hold of data about West Campus’ growth, we pretty much had no choice but to put it in charts.

Part 1: Understanding the scale and speed of West Campus’ growth

West Campus has grown fast

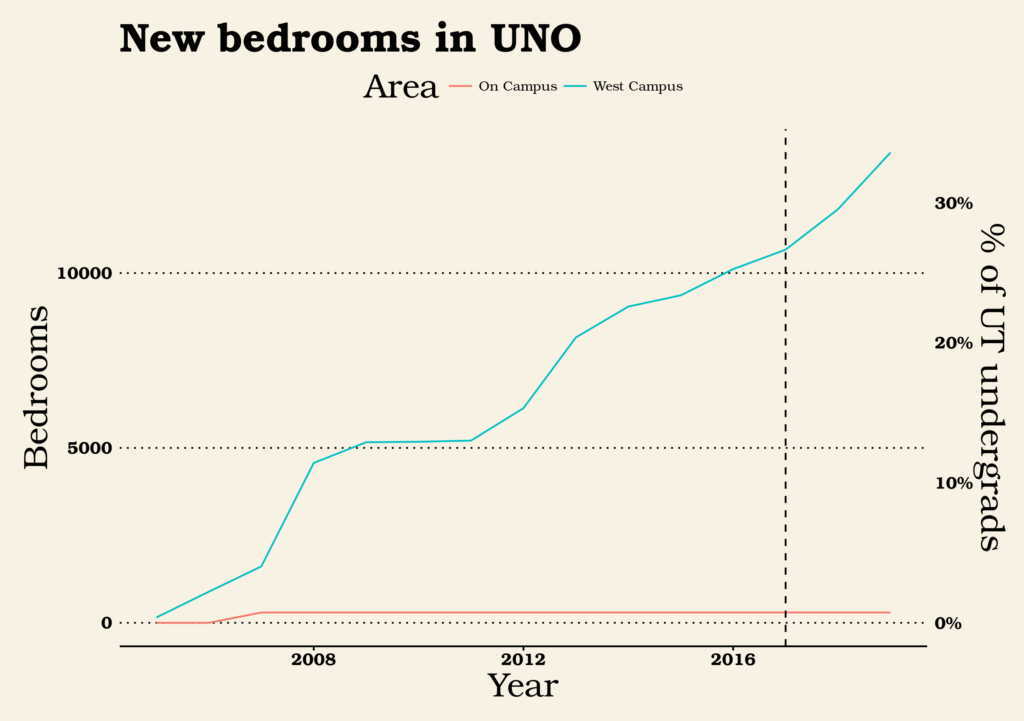

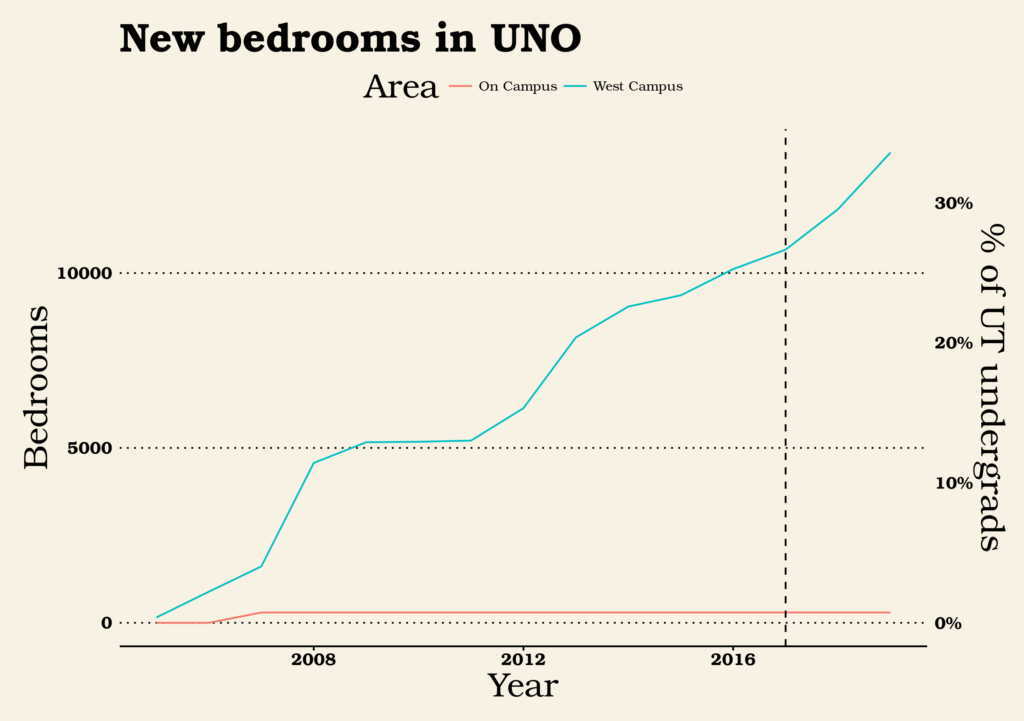

Since the creation of the University Neighborhood Overlay in 2004, there has been a pretty steady growth of new homes with a brief financial-crisis-induced break in 2009-2010. The numbers are really quite stupendous: over the course of a decade, essentially a new town of 10K people has been added to what was already one of Austin’s denser neighborhoods.

In this chart, I show two equivalent axes: bedrooms (on the left) or % of UT undergrads those bedrooms represent (on the right). I chose to use bedrooms rather than units because of my intuition that student housing is typically occupied by one person per bedroom, so a 4-bedroom unit really does house twice as many people as a 2-bedroom unit. (In other housing, a 4-bedroom unit may mean that one or more bedrooms are being used as a study or guest room.) The blue line shows the number of new bedrooms created in the UNO overlay, while the red line hugging the bottom shows the number of new bedrooms created by new dorms on the UT campus itself. Numbers after 2017 are projections based on city filings rather than completed units on the ground. At the rate UNO is growing, approximately half of UT undergrads will live in new units created under UNO by 2023.

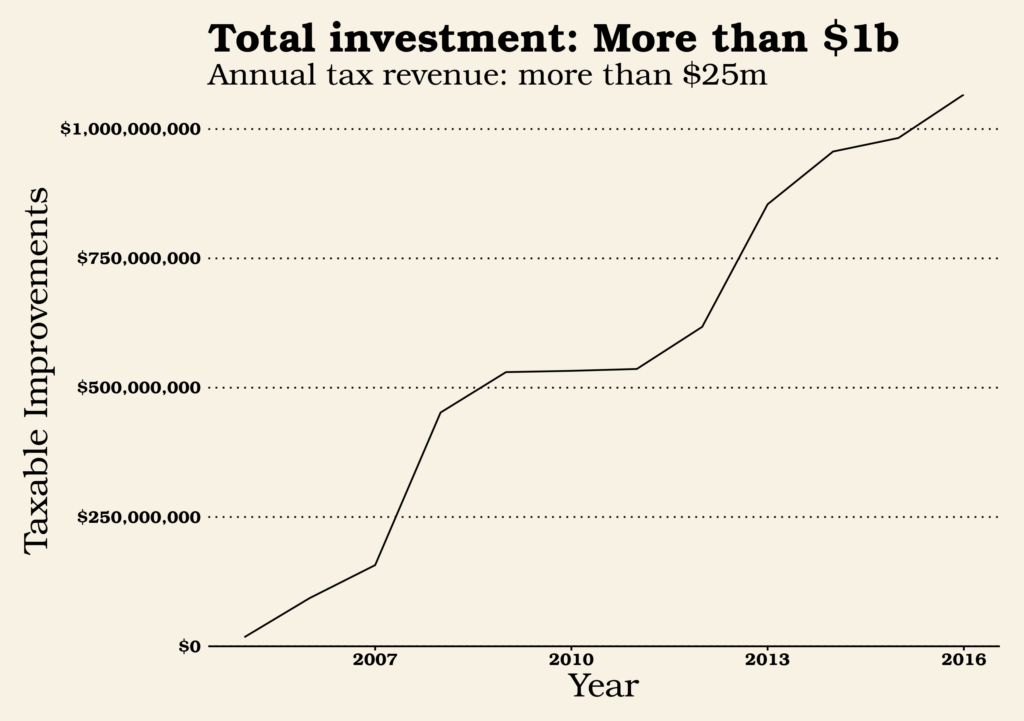

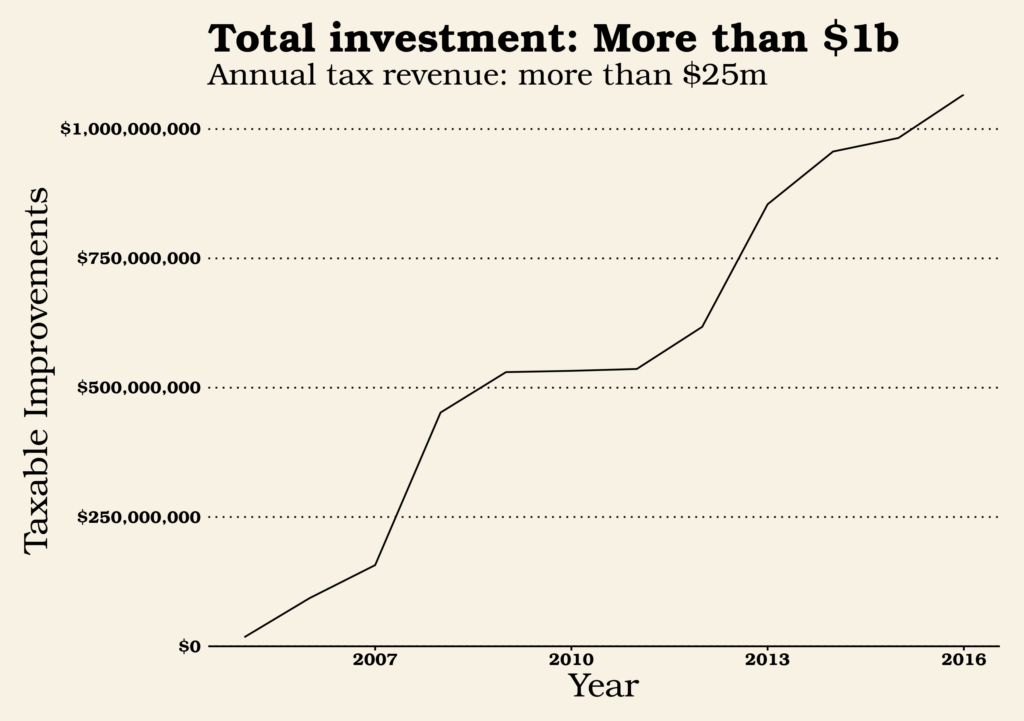

A lot of investment

How much does it cost to build out a neighborhood? Using 2017 tax valuation, the UNO buildings alone (not counting the land they sit on) were valued at a bit more than a billion dollars. For comparison, Austin’s last affordable housing bond was for $65m and the capital costs of Austin’s proposed 2014 light rail bond was about $1.5 billion. Each year, the buildings in UNO contribute more than $25m in property tax revenues to the various local government taxing entities: the city of Austin, Travis County, Austin Independent School District, Austin Community College, and Central Health.

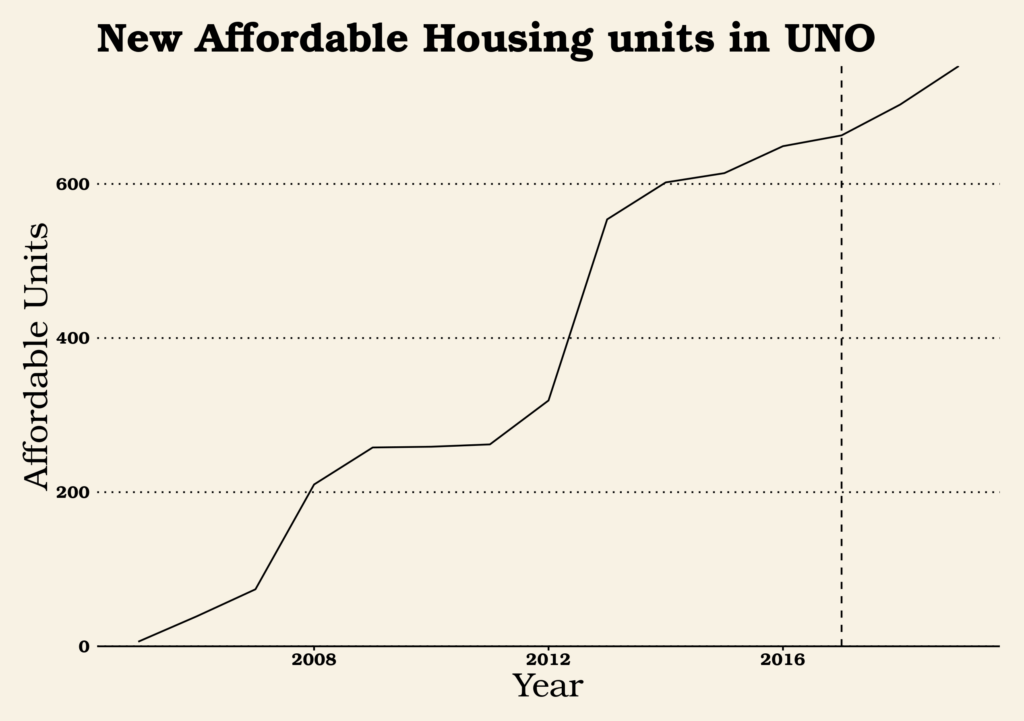

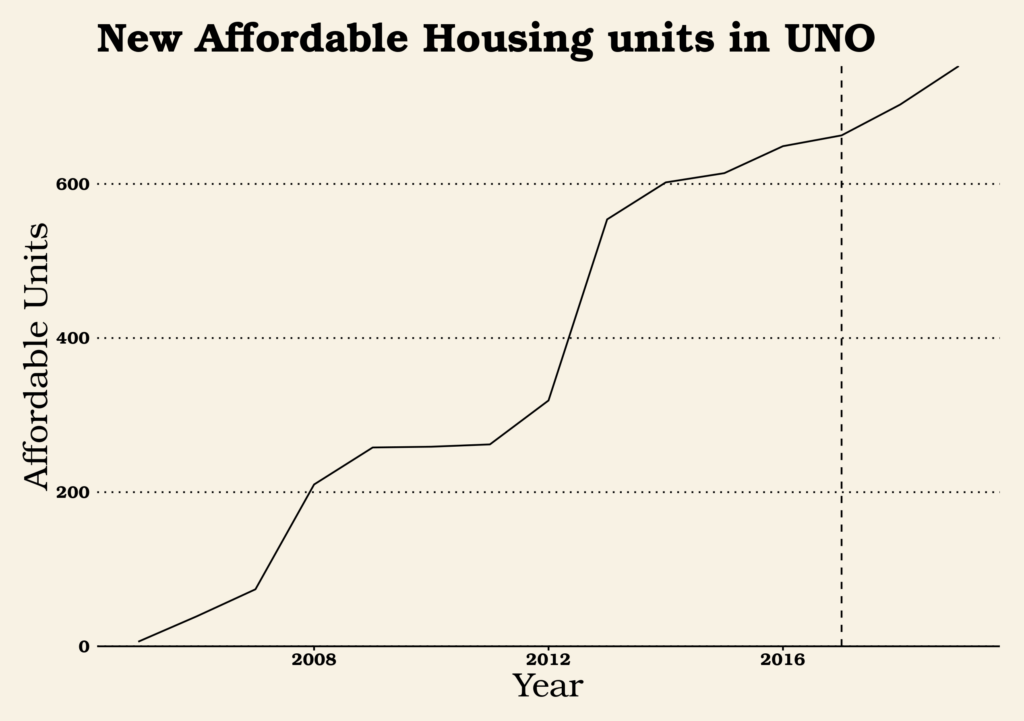

A lot of new income-restricted apartments

West Campus is home to one of the largest concentration of developments in Austin with apartments specifically for people below certain income levels. There are two reasons for this: 1) as part of the new rules for building apartments, developers are required to set aside a certain number of units for eligible people, and 2) there has been a lot of development in West Campus.

Part 2: How UNO has changed over time

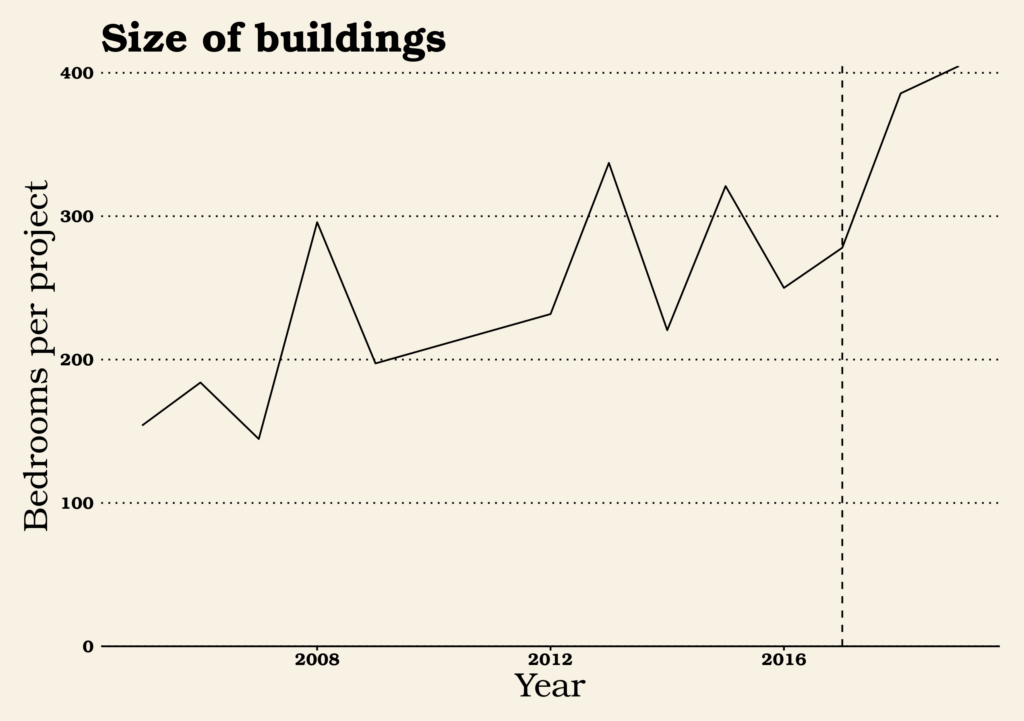

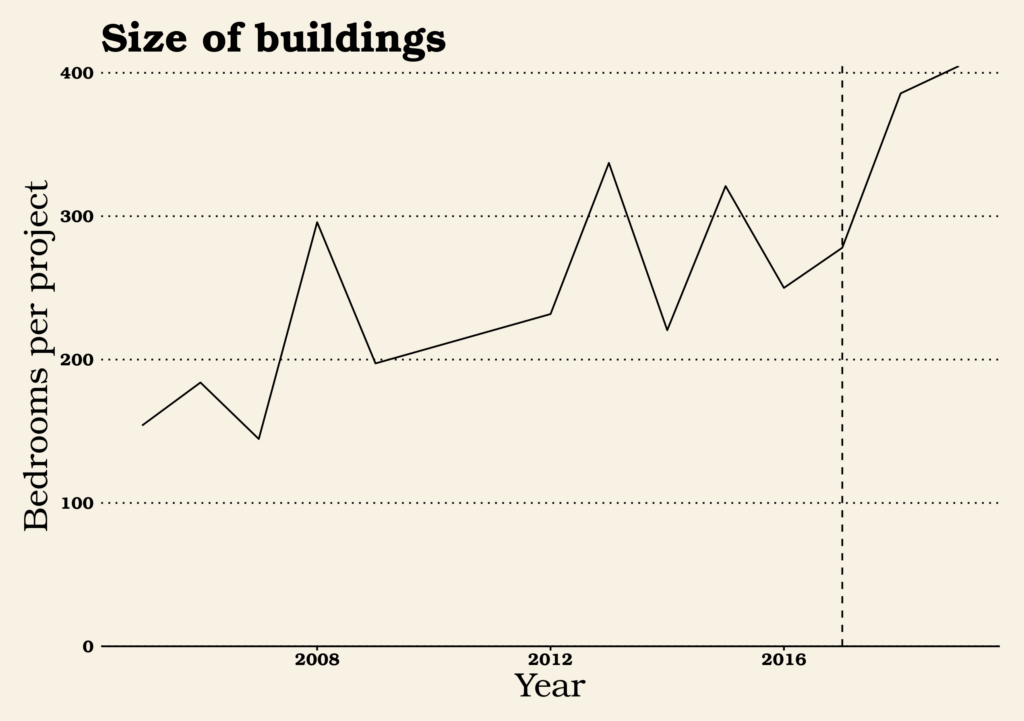

Buildings are getting bigger

Buildings are getting bigger overall, as expressed by number of bedrooms per project. I’m not sure why this would be; perhaps easier-to-finance mid-rise buildings have proven the way for larger high-rise projects. Perhaps the most easy-to-build sites were in the lower height districts and investors are moving on to the more difficult-to-build sites in high-rise districts.

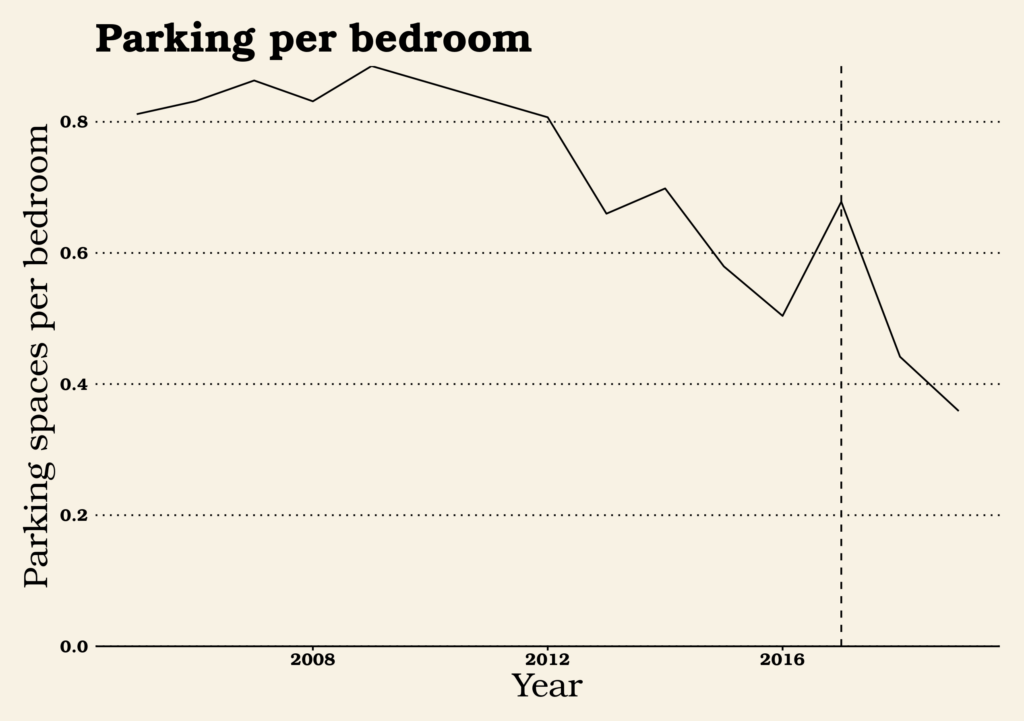

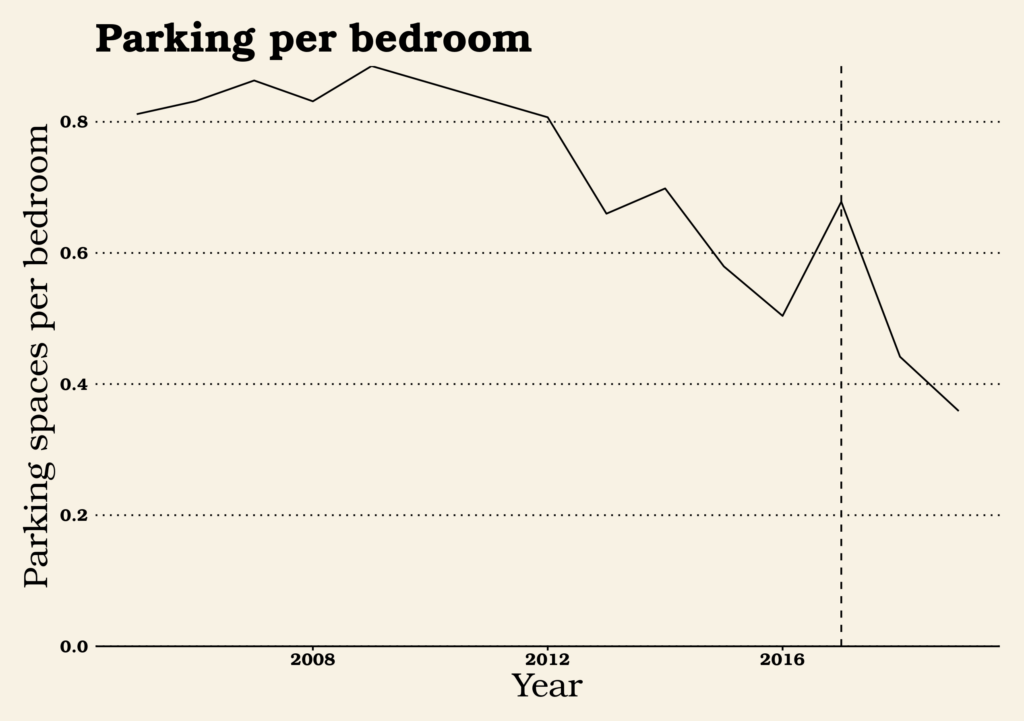

Parking by bedroom

Over time, the number of parking units added per new bedroom built has dropped precipitously from a high of nearly 0.9 parking spaces per bedroom to 0.5 in 2016 and an anticipated 0.36 in 2019. Apparently, when we build places near other places, more people can get around without a car. There’s a number of ways these change might be explained:

- Developers and financiers have become more comfortable with building less parking as earlier buildings saw less parking used than anticipated.

- As more commercial amenities have moved into the neighborhood like the Fresh Plus grocery store, fewer students have needed cars.

- Younger people more generally have lower preferences for having cars with them at school than they used to.

- Developers have gotten better at managing city rules to find ways to avoid expensive required parking. (More on this later.)

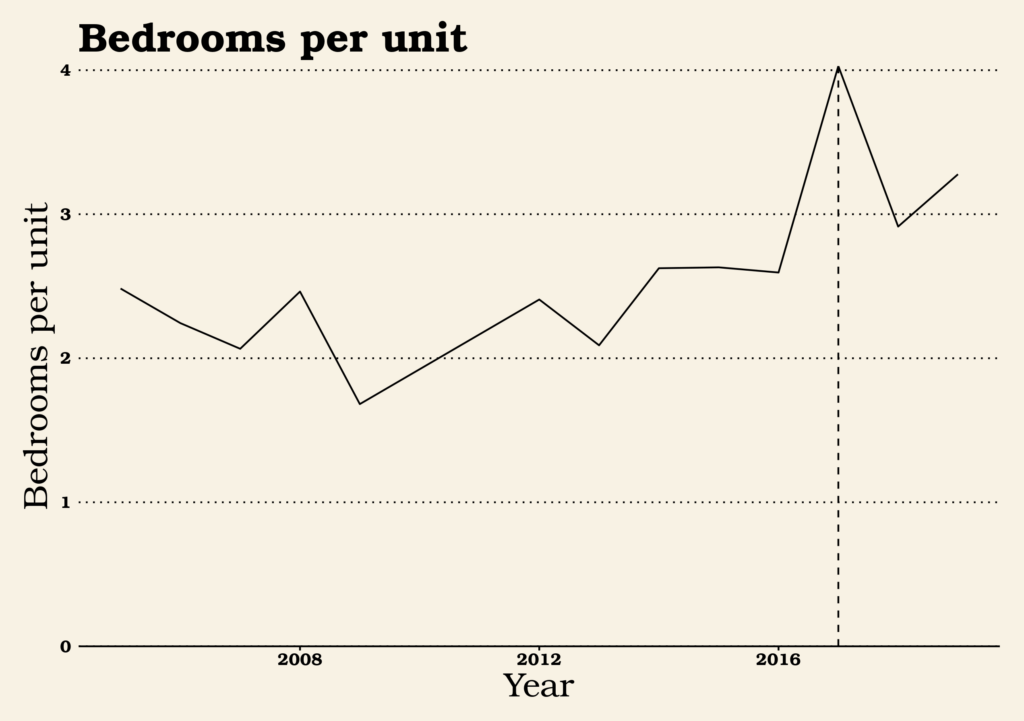

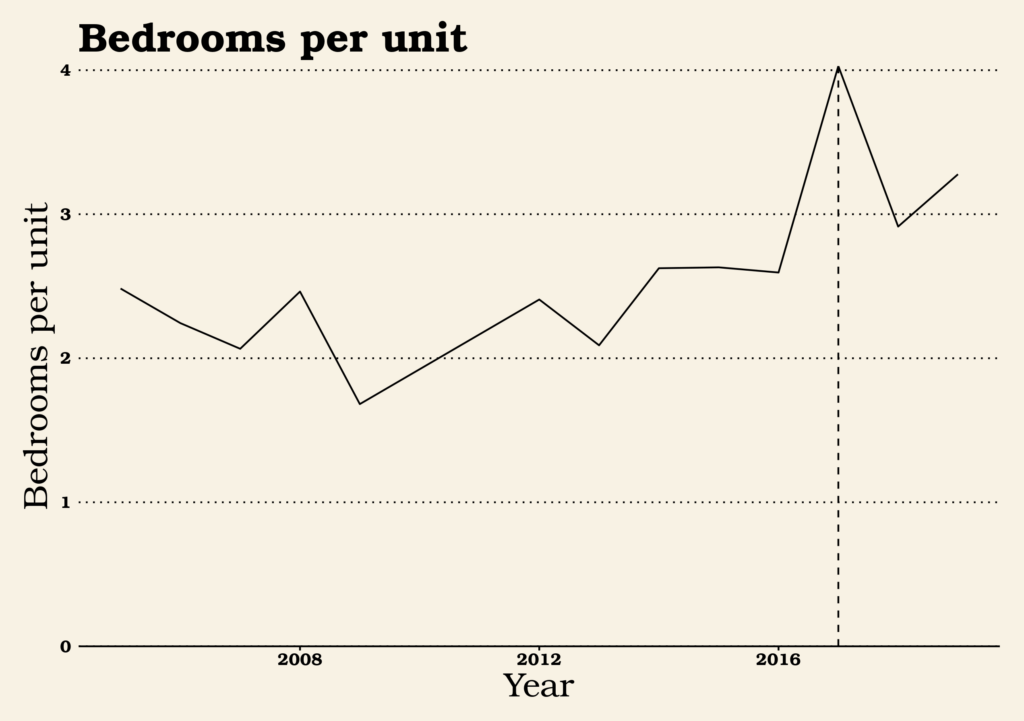

Bedrooms per Unit

The number of bedrooms provided per unit is a major way that West Campus departs ways from the rest of Austin. Developers typically build studios and 1-bedroom apartments to accommodate the many 1- and 2-person households the city is adding. In West Campus, developers have always built more bedrooms per unit, probably because students are more willing to share a suite with unrelated roommates than many non-students. Of late, though, the number of bedrooms per unit is going even higher. Why? I have a hunch.

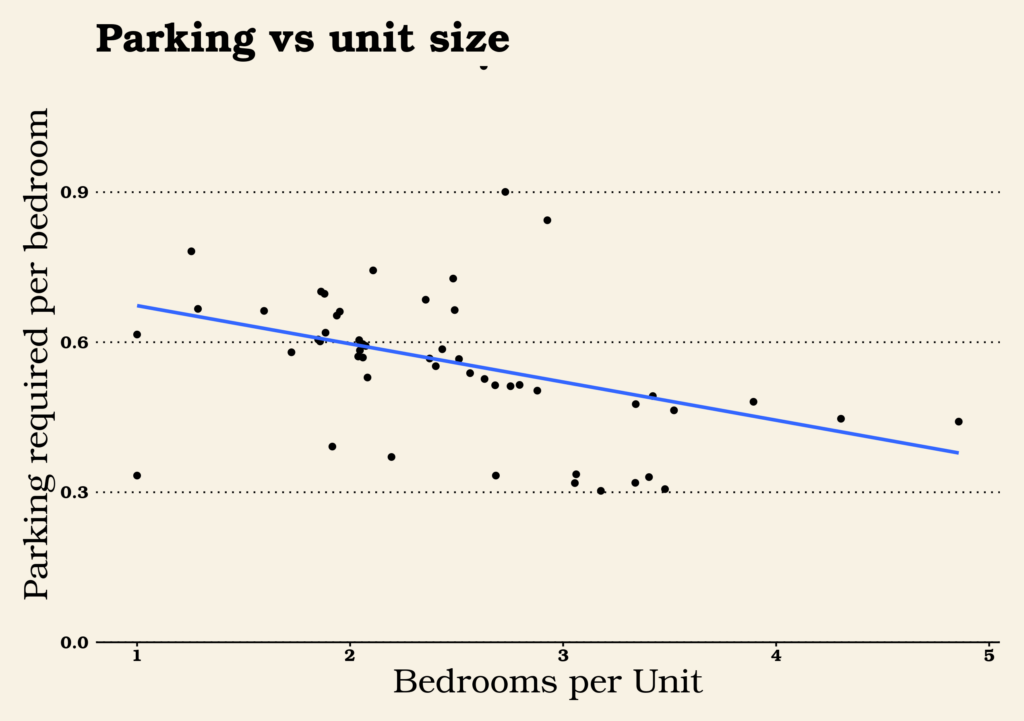

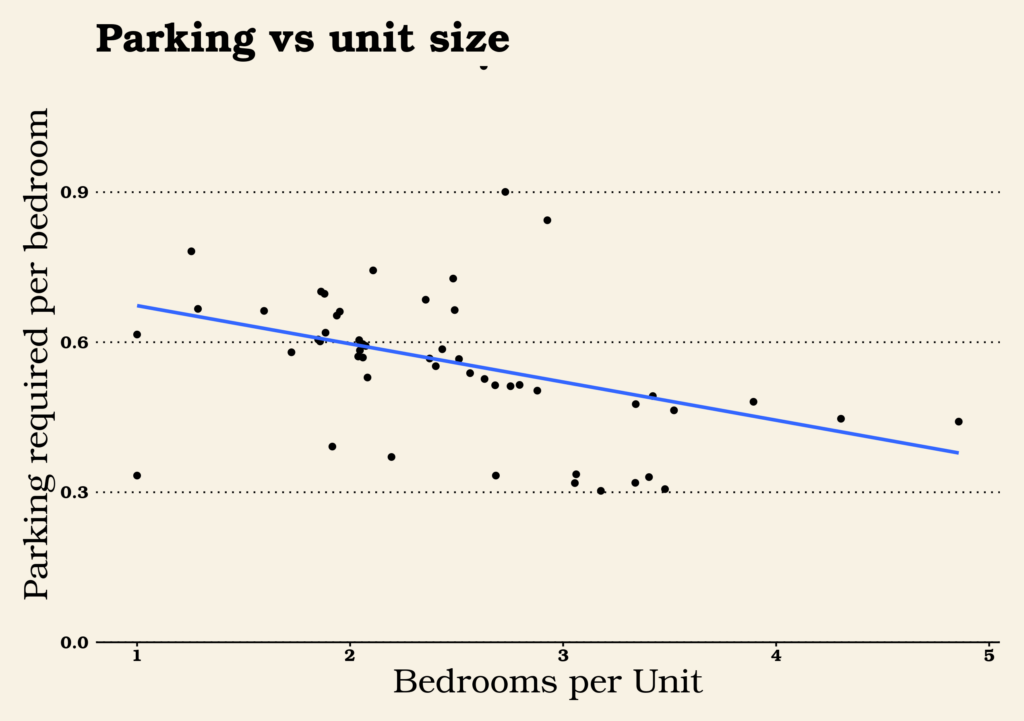

Parking by Unit Size

This is a trickier chart than the others. On the bottom axis, there’s bedrooms per unit. On the left axis, there’s parking spaces required (not built) per bedroom. The dots and the blue trend line both show that, generally speaking, the more bedrooms provided per unit, the fewer parking spaces a developer is required to build.

Based on the trend toward less parking per bedroom and more bedrooms per unit, my hunch is that developers have figured out that parking is not an amenity that enough students want or are willing to pay for to justify the fairly high costs of building it. So now they’re trying everything they can to avoid the expense of building unwanted parking garages, including build bigger suites for which they aren’t required to provide as much parking. If this is true, it’s another example of a remarkable property of zoning codes: they always have unintended consequences. Zoning code didn’t set out to decide how many college students should group together into a suite, but it might well have decided it nonetheless.

[Edit: A dissenting view comes in from friend-of-the-blog Tyler Stowell. See below.]

Conclusions

This has been a fun romp through a little dataset. Let’s reiterate some of the conclusions I’ve drawn:

West Campus shows little signs of slowing down

There are sometimes worries that when a part of town allows denser housing, there will be a big bang as all the most likely sites get developed and the ones that remain all have special problems. If that’s the case with West Campus no effects are obvious. New sites come on to the market all the time and there are still surface parking lots or low-rise buildings that are prime targets for redevelopment. We could well see new West Campus buildings account for 50% or more of the undergrad population before long.

The city still requires too much parking

The trend we observed toward fewer and fewer parking spaces being built — and especially the trend toward weighting the unit mix toward parking-light high-bedroom units — tells me that developers are seeing little use and little market for their parking. With Bcycle rideshare taking off on top of the existing walking, biking, and bus routes, most students in West Campus just don’t want or need cars. Eliminating parking minimums would also allow developers to be more creative in other areas, providing different amenities or lower costs.

The city regulates way more private investment than it makes public investment

So far, rebuilding West Campus has been a $1B project, far dwarfing the amount of money the city has spent directly or indirectly on housing development. Most of the time, we don’t think of it as a single “project” because there is no one single coordinating entity controlling what buildings get built in what order. But it was created as a result of a city policy change. Even the smallest changes to city policy, in this case only affecting a single neighborhood, can end up affecting far more private investment than direct municipal spending affects.

[Note from friend-of-the-blog Tyler Stowell:] I’d disagree with one of your points though – my observation is that the higher bed/unit ratio isn’t a way around parking requirements, it’s a cost cutting measure. Bedrooms are cheap and pay rent. Kitchens and bathrooms are expensive and don’t pay rent. Diluting the cost of kitchens/baths over more beds equals higher profit for the developer. And this works in west campus for college students who might’ve lived in Jester last year. Not so much in other markets. The parking is always a target percentage of bedrooms and truly is market driven (eg. my last project the developer wanted to provide a space for 80% of bedrooms). Some projects take the full reduction allowed by UNO, but some go higher.