The hottest political topic in Austin right now is a proposal by the owner of the Major League Soccer franchise Columbus Crew to lease space on a city-owned parcel in North Austin. To see the more colorful side of the debate, browse the #MLS2ATX or #SavetheCrew hashtags on twitter:

Just a regular #CrewSC tailgate. #SaveTheCrew pic.twitter.com/JcGJHv6Vld

— David Miller (@DavidMiller0789) August 11, 2018

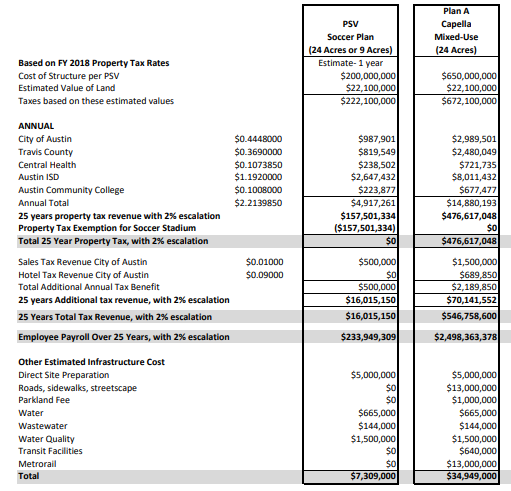

I’m not going to rehash the debate, but rather pick out one piece of the “no” side’s argument, led most strongly by CM Leslie Pool: the opportunity cost of leasing the parcel for a stadium. While the lease would be a financial positive for the city compared to doing nothing on the land, that isn’t the only other option. A nearby property owner/developer, for example, has proposed an alternative plan where they buy the land, build a relatively dense mixed-use development, and pay taxes annually estimated at $15m per year. The “opportunity cost” argument is a really good argument. In fact, this argument is so good that I’ve made it a few times myself over things like the immense value to the city of new construction in West Campus, or the potential opportunity cost of a tax-free convention center annex. (Proud that the proposal I successfully passed in the Visitor Impact Task Force recommended a future convention center annex remain taxable.) In fact, this is such a great argument that I desperately, desperately wish people used it more often. In a previous policy decision, the decision on what a Planned Unit Development agreement would look like for “the Grove,” a plot of land off 45th Street near Mopac, one of the leading opponents of a similar sort of dense mixed-use development was the very same CM Pool and I don’t recall her carefully weighing the benefits of limiting residences there against the tax revenue the city would forego by allowing more construction.

But the point isn’t to discredit the argument by calling hypocrisy. The argument is really good! It’s an argument worth making! While large developments like the Convention Center annex, McKalla Place, or the Grove are relatively visible because they’re covered in local media and debated by City Council, virtually every land use decision that the city makes has a fiscal dimension, yet we rarely ever think about it. (To his credit, Council Member Flannigan frequently invokes the fiscal impacts of development patterns.)

So, let’s talk about fiscal impacts!

Rule 1: Compact development tends to be more valuable

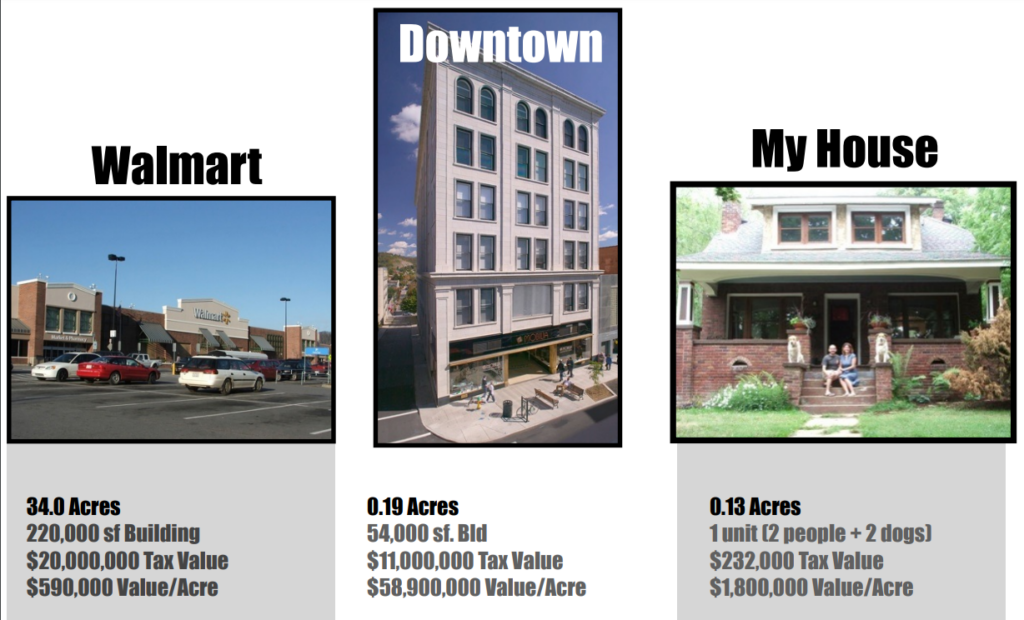

In a fantastic presentation prepared for the Downtown Austin Alliance, consultant Joe Minicozzi compared the fiscal returns to a city from different kinds of development:

While a Walmart may have eye-popping tax values because it’s such a large single development compared to a traditional low-rise office building or house, a low-rise office building also requires much less space to deliver value. Many of a city’s costs, like building streets, scale by the linear mile not by the person. It costs much much more for a city to provide services to a Walmart than to a downtown city block. For residential buildings, the same rules apply. If a city has 5,000 residents, it’s easier to provide them services if they live in a single cluster of 250 acres than if they spread out to 4,000 acres. In Austin, we see these expenses in items like the five fire stations the fire department has requested to cut down response times on the outskirts of the city. I don’t begrudge people who live on the outskirts fire stations. But I do wish we had denser land development patterns in the central city to better take advantage of our existing fire stations and roads.

Rule 2: Value is driven by making great places for the long term

Take a look at the Capella proposal again. In addition to the $15m in annual tax revenues, they will pay other costs: for example, $1m in parkland dedication fees. Additionally, they have offered $22m for the purchase of the land. These types of one-time fees, both voluntary and required, typically dominate policy discussions but they are drops in the bucket compared to the long-term tax revenue from building a great place that could last a century or longer. The financial life-blood of a city is not in one-time fees but recurring taxes levied every year on great places for its residents to live, work, and enjoy themselves.

When a city considers the fiscal impact of a development, the question it should be asking itself is not how much can we extract from this developer today but: is this developer making a place that 50 years from now people will still want to be in and still be willing to pay taxes on? The Littlefield and Scarbrough Buildings, two modest 8-story downtown Austin office buildings that were anything but modest at construction time pay close to $1.4m in taxes year-in and year-out more than 100 years after they were built, after their historic building tax breaks!

Rule 3: Taxes are only one of many benefits to consider

Of course, not all of life can be boiled down to profit and loss, tax revenues and maintenance costs. Parks cost taxes to maintain and don’t directly raise taxes themselves, yet most of us love them. Comparing the often difficult-to-quantify benefits with the easy-to-quantify costs can be difficult and frustrating, as both CM Pool and CM Flannigan express here:

👀 #atxcouncil pic.twitter.com/tb91veWJZO

— Nina Hernandez (@neenthirteen) August 11, 2018

There’s no obvious right decision on a given question. Is it worth it to Austin to pay millions of dollars in maintenance and forego even more than that in taxes for things like the Butler Hike and Bike Trail, Zilker Park, or Barton Springs? The overwhelming majority of Austinites would say yes. Is it worth it to Austin to forego millions of dollars in taxes to “bring people together” through a soccer stadium or to prevent dense development on the former TxDOT site? Could it be worth it to create another West Campus, throwing off tens of millions in tax revenue annually to fund things like parks and schools and soccer fields? Austinites are much more split on these questions and that’s why they’re political decisions. But if we want to make good choices, we need to understand the costs and benefits clearly.