Last post, I talked about physical alternatives that would let us #parktheplinth. Or in normal terms, ways to build downtown towers that don’t have giant parking plinths. Before that, I also discussed the regulatory reasons why large parking plinths are common downtown, but much less so in West Campus. So, today, let’s combine the two thoughts: what regulations could we have downtown that would encourage people building towers downtown to use some of those alternatives to parking plinths?

downtown

How West 6th Was Accidentally Fixed for the Age of Scooters (and How to Keep it Fixed)

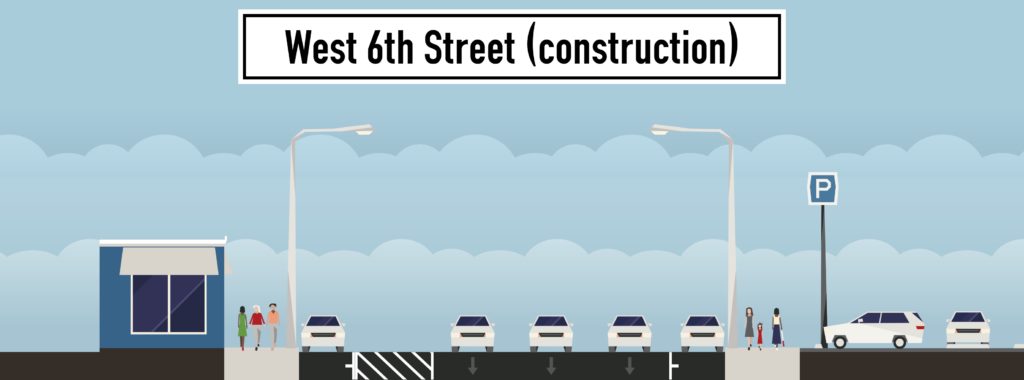

There’s a new development on West 6th Street downtown. A six-story hotel going by the name “Canopy By Hilton” is being built next to Star Bar, between Nueces and Rio Grande (details at Towers). Space being rather constrained next to the hotel site, the developers have rented space to stage demolition and construction on the street itself, temporarily narrowing 6th Street:

For the last week, West 6th St has been narrowed between San Antonio and Rio Grande to make room for construction of a hotel. As a result, the street feels much safer. @austinmobility, let's make it permanent. pic.twitter.com/Tllk7FzzAQ

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) September 18, 2018

Here’s what 6th Street looked like pre-construction from the perspective of the Google Maps street view car:

Let’s take that and simplify it a little in StreetMix:

Now, let’s look at what it looks like today:

Let’s simplify that in StreetMix again:

A funny thing happened on my walk home recently. I noticed that there were no cars parked in the parking spots on the left hand side of this picture and a number of people were using it to scoot in. The blocked-off lane was functioning as a buffer between the scooters and car traffic, thus creating a temporary protected lane.

If the city kept this configuration but made it slightly more permanent, here’s what it might look like in StreetMix:

I’ve replaced the car parking on the left with a two-way bike/scooter lane and updated the buffer so that people can use it to park scooters. Also, I threw in some potted plants as buffers to discourage people from using the buffer, by accident or impatience. The buffered area could not only fit scooter and bike parking, but it could do so and still leave room for a few taxi/Lyft pullouts. Is this the ideal configuration of West 6th? No; I definitely think a professional street designer could do better. But it shows how even a very low-dollar intervention could simultaneously remove some of the many annoying and at times dangerous conflicts on downtown streets:

- Conflicts between people riding scooters and people driving cars

- Conflicts between people riding scooters and people walking on sidewalks

- Conflicts between people parking scooters and people walking on sidewalks

- Conflicts between people getting picked up or dropped off in Uber/Lyft cars and people driving cars, scooters, or bikes.

Of course, just because this configuration wouldn’t cost much money to execute, it doesn’t mean there aren’t non-financial costs:

- 13 meter spaces are removed from the street, forcing more drivers to pay market rates to park their cars in parking lots or garages.

- One car-sized lane has been removed from the street, reducing the peak capacity and slowing the time it takes for drivers to get from downtown to Mopac at rush hour.

Conveniently, Austin has more parking downtown than it has land downtown. (This is true because parking spaces are largely stacked on top of one another).

The amount of parking in Downtown Austin is equal to one surface lot larger than Edwin Waller's original city plan. pic.twitter.com/1HE8bbCcTy

— Caleb Alan Pritchardo (@cubbie9000) May 14, 2018

So, the question becomes not one of finance but one of values and vision. Are we a city that values safe, convenient streets for walking, biking, and scooting, as well as driving, or are we a city that can’t wait the additional two minutes to get on Mopac?

Does transportation serve people or do people serve transportation?

No big city has solved either of two problems: making car traffic flow smoothly or making parking simple and cheap. The issue isn’t that governments in every city are bad, though sometimes they are, or that traffic engineers didn’t anticipate the future, though sometimes they didn’t, or that drivers drive too aggressively, though sometimes they do. The issue is that these problems are impossible to solve due to basic geometry. You can fit more people close together than you can fit cars close together. In a small town, you can fit all the people and the cars together without much difficulty. But as a city grows larger, it’s easier to accommodate people, which are relatively small, compared to cars, which are relatively large.

There are a million ways to think about this that all come to the same conclusion. Caleb Pritchard has pointed out that there is more space downtown devoted to parking cars in downtown Austin than there is space in all of downtown (some of the parking spaces, of course, are stacked in multi-level garages, so the math works):

The amount of parking in Downtown Austin is equal to one surface lot larger than Edwin Waller's original city plan. pic.twitter.com/1HE8bbCcTy

— Caleb Alan Pritchardo (@cubbie9000) May 14, 2018

New office buildings in Austin devote as much space to storing cars as they do to storing people.

Glass on 500 W 2nd gives a nice illustration of the building's split into car floors (unlighted, bottom) and person floors (lighted, top) pic.twitter.com/QeyZMSTa89

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) February 21, 2018

This is ugly and wasteful and terrible for the environment and extraordinarily expensive. It requires people to spend a long time and sometimes a lot of money circling up floors or circling city streets to find parking spaces and people hate the process with a fiery passion. People’s (un)willingness to circle up floors to park is the binding factor limiting the size and creativity of downtown office buildings in Austin. Car parking is the reason our office buildings are shorter than our residential towers — illustrated nicely by how the Sullivan’s Tower got shorter when it was converted from apartments to office. Car parking is also the reason our office towers are shorter than office buildings in less car-oriented cities like, say, New York or Houston. But despite all that, it kind of works. Every work day, 100,000 people find a place to store 2,000 lbs of metal within a square mile of land, so that they can be close enough together to hold a meeting in the conference room or walk to the courthouse or the state house or the post office or city hall or each other’s offices or any other places they need to go as part of their work day.

As bad as the parking situation can get, it’s good news compared to figuring out the logistics of moving them around the city. We can make many more multilevel parking garages in downtown Austin before we run out of space, but stacking cars on top of one another when they’re driving (by building tunnels or elevated streets) is prohibitively expensive for more than a few major highways. Even then, the best you can hope for is two or maybe three levels that people hate to drive on, look at, or live near. You can widen streets to handle more cars, but the more space you use for streets, the less space you have for the places people are using those streets to go.

Another option is to spread buildings out. Instead of a huge chunk of people coming together to work downtown, make many different employment nodes around the city. This can work, to some degree. But the reasons people needed to be in close proximity to one another don’t go away, so the cure is often worse than the problem. Instead of finding a way to get people who need to be in proximity with one another into a small walkable area, you require them to drive half an hour to get to any meeting they have, creating even more traffic and making things even worse!

There’s simply no solution that allows people to get wherever they want in a big city in a car without facing traffic along the way. Implicitly, when we develop new buildings, our development rules recognize this fact. New buildings are required to perform a “Traffic Impact Analysis” which uses arcane, inaccurate, and context-free rules to model how many times per day somebody will arrive at or leave a building, depending on what kind of things people do inside the building. Rules which require a TIA often limit the number of so-called “trips generated” for a particular development.

Why do we say medical offices "generate trips?" Medical need generates trips. Medical offices meet those needs. Same for all types of trips.

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) July 15, 2016

The basic idea behind trip generation limits is the understanding that big cities and cars are fundamentally incompatible. Rather than limiting the use of cars, limits on “trips generated” are a vain attempt to limit a city from growing too large to outgrow the usefulness of cars. The reason why this attempt is in vain should be apparent: trips aren’t generated by buildings, but by needs. Sprawling trips out over a bigger area merely forces people to drive even further, creating even more traffic.

Of course, just because cars and big cities have fundamental conflicts doesn’t mean cities can’t continue to outgrow the constraints of car-oriented development. There are countless solutions: buses, trains, bikes, scooters, sidewalks, dollar vans, etc. The details of each solution vary but the overarching idea is very similar: 1) make trips shorter so people don’t need to travel as far to get to the places they want and need to go, and 2) fit people closer together while they’re making trips to make more efficient use of each street.

Hint: pic.twitter.com/R4NM8IFb0A

— Caleb Alan Pritchardo (@cubbie9000) May 17, 2018

There have been some positive ideas on reforming TIAs to use these solutions, California being the best example in the US. But I’d like to propose a different way of thinking what a TIA could be. Instead of assuming cities are tied to cars only and then limiting developments to the constraints that cars have, we could start with the development we want and then require that this developments accommodate whatever transportation system is necessary to complement it. Instead of trying and failing to scale cars to a level that they simply aren’t capable of handling, we find the transportation system that is actually capable of handling the development.

For example, if a developer proposes a development whose size or density tips past the point where most trips can be comfortably done with cars, she would be responsible for providing street designs that include different ways of getting around: bike lanes and bike corrals, or designated places to store dockless scooters, or proximity to a transit line.

There is a sense in which we do this already. Austin’s land development code, like many others, requires infrastructure for cars (mostly parking) but allows developers to provide less of it if they provide alternative transportation infrastructure (e.g. parking spaces designated for shared cars like Car2Go, showers for bicyclists). But these efforts are piecemeal and complicated. All too often, TIAs are wielded as weapons to prevent homes and offices, when instead, we could make them a tool to make any development work.

Vote one more time on your favorite Congress Avenue

You readers responded very well to my call for new designs for Congress Avenue, and selected this place-oriented design by Mateo Barnstone:

Now, the professionals have weighed in and come up with three options for streets, as well as three options for a design language. (Scroll down to the May 15 event.) All three feature protected bike lanes, wider sidewalks, and more street trees, but they differ in the details:

So it’s your turn to vote on options again, but this time in a city survey that could affect the final design chosen. Survey here!

The one little rule that decides where Austin’s towers build parking

Not every tower in downtown Austin looks exactly the same, but there is one defining characteristic that describes almost all of them: parking. Most towers rest on top of what they call in the industry a parking plinth, the tower base where folks store their cars. (Plinth is a Swedish word meaning ugly thing.) Here’s a typical example, the Seaholm Tower in southwest downtown.

On the ground floor, there’s a restaurant. Above that, the area with small and sporadic windows is the parking garage. Above that, the area with balconies is where the condos live. Simple, effective, but not always super sightly, at least to my tastes. Why not build parking underground, freeing up aboveground levels for more homes? For one thing, building underground car parking is very expensive. The exact difference varies by site but I’ve seen estimates that moving a parking space underground can add $10K to the cost of the space — and the further you have to dig, the more expensive it gets. So perhaps underground parking is reserved for the most expensive buildings?

No, even in Austin’s newest luxury towers you see aboveground parking:

Parking underground is just too expensive for Austin, or so I thought, until Sid Kapur pointed out to me that there is somewhere in Austin building underground parking:

[tweet 938849429121060865]

Yes, of course, West Campus (aka Bizarro Austin) is building underground parking. See James Rambin’s writeup at sister site Austin Towers of projects like Skyloft and Aspen West Campus with four stories of underground parking. So why do developers building student housing decide to put parking underground? Are students more discerning aesthetic connoisseurs? Sorry, students, but I doubt it. I have an alternate theory.

There are many different ways that zoning codes can limit the amount of space that can be built. In downtown, the binding constraint preventing even larger buildings is something called Floor Area Ratio or FAR: roughly, the square footage of climate-controlled space in a building divided by its footprint. In West Campus, the binding constraint on the size of a building is regulations on maximum height. Crucially, parking counts toward a building’s height but doesn’t count toward its FAR. If a developer in West Campus moved their parking from below-ground to above-ground, they would have to remove apartments in order to fit it in, costing them a lot of money in lost rent. Developers downtown, though, don’t have a height limit so building a parking plinth costs less than putting parking underground, doesn’t use up the building’s FAR, and even makes the residential units more valuable by giving them better views.

If my theory is true, it makes some predictions: portions of northern downtown that are slated to be rezoned with height-constrained zoning categories (CC-40 and CC-60) will likely see underground parking, while the FAR-constrained central business district will continue to see parking plinths. Indeed, the condo building I live in downtown was built pre-CodeNEXT but it had height limits imposed as part of the rezoning process and consequently built most of its parking underground:

Why do so many downtown buildings cut corners?

If you’ve walked around downtown Austin, something you’ve probably noticed is that a lot of buildings built recently and a lot of buildings under construction have cut corners. No, I don’t mean they’ve used shoddy construction. I mean that, literally, they’re shaped as a rectangle with a corner cut off. Sometimes there’s just no building there; sometimes there’s a much shorter part of the building with just the tower component missing. It’s so common that it’s almost becoming Austin’s signature building style. How come?

How the Convention Center Expansion Proposal Has Improved and What’s Still Needed

Last November, I was appointed as a member of the Visitor Impact Task Force created by the City Council to look into the positive and negative impacts of tourism in Austin, as well as put together recommendations regarding the potential expansion of the Convention Center. I came in an expansion skeptic but I voted for expansion. Y’all deserve an explanation. So here are four ways the Task Force’s recommendations for the convention center expansion improved on the proposal we had coming in, followed by some thoughts on what’s needed from here.

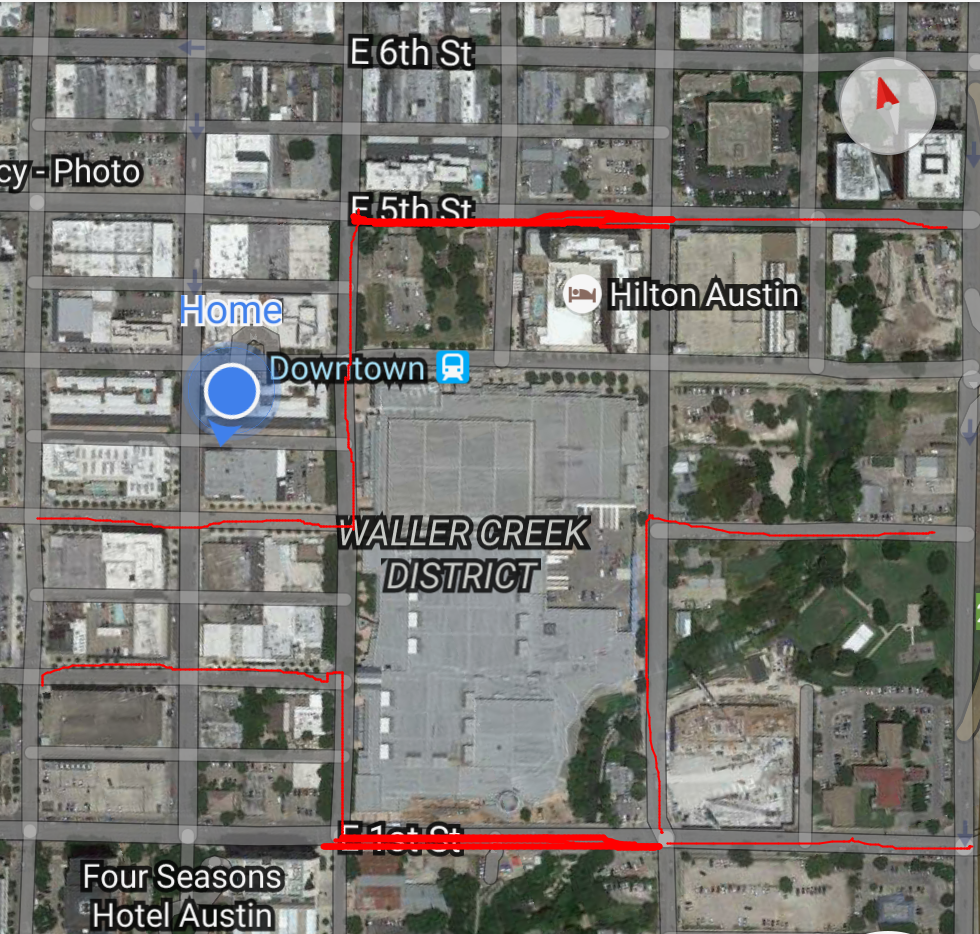

1 Keeping the Street Grid In Place

Street connections are vital for making great places. For people driving cars, they mitigate traffic by providing alternative routes. For people walking, they increase the storefront-to-walking-distance ratio, making more destinations like restaurants and bars in walking distance. Not all uses are compatible with street connections — in downtown Austin, many potential street connections near government buildings are blocked off for security reasons. Some alleys (small streets in a sense) have been removed because they’re incompatible with the uses of the building.

One of the worst areas for street connectivity downtown is the existing Convention Center. I lived next to it for years, walking everywhere and in every direction on my own two feet before I discovered on a map that there was a city park blocks from me on the other side of the Convention Center. The lack of streets in the area made it harder to discover destinations even when they were there. The original plan for the expansion doubled down on this unwalkable dead area by closing off two more city blocks (2nd and 3rd St from Trinity to San Jacinto). Following the recommendations of the Design Commission and many architecturally-oriented citizens, the Task Force specifically called out maintaining the street grid as one of our design recommendations.

2 Bringing More Uses to the Southeast Quadrant

The Convention Center is a rare nine-city-block square downtown with a single use. The convention center’s maximum practical capacity is about 65% of the days of year, due to days like Christmas when nobody wants to hold a conference and the setup/teardown time for flipping conference space. Even when conferences are in town, conferences themselves are not typically all-day affairs, so there are still significant dead times. As a result, while the convention center area can feel very crowded at specific times when conferences are letting out, a lot of the time it feels empty. As many locals told me, “I have no reason to go there.” Right in the middle of downtown, it’s home to many storefronts that don’t even bother opening except for special events.

The original Convention Center plan recognized this and recommended integrating retail and restaurants into the expansion, but this really didn’t go far enough. Locals without a reason for being in the area rarely go out of their way to get there. At the suggestion of the Design Commission, the Task Force recommended that any Convention Center design be integrated not only with ground floor retail but also with other uses such as office or residential. This should both help locals (both residential and office space are at a premium downtown right now) and visitors, by giving visitors a chance to explore the same Austin as locals. In this way, you could conceive of the project as a convention center expansion with a residential component, or merely another residential tower, but with room for the convention center in it.

3 Potentially Saving Money by Integrating with Other Uses

Estimates for the Convention Center’s plans for redevelopment came it at an eye-popping $559m before land acquisition costs, estimated at about $100m or more. The cost estimates were done without a detailed design document, so they could be significantly off. The Task Force’s recommendation described above (housing expansion within a larger private sector development) has the potential to cut down on these costs by sharing development costs across many uses. Without detailed design estimates, we can’t know whether this will pay off, but there’s reason to believe it could!

4 The Convention Center Expansion will be integrated with other efforts

The convention center’s original expansion plan recognized the need for any new building to not be an island unto itself but integrated into its surroundings. Toward that end, it spoke of not just a convention center expansion, but an entire Convention Center District.

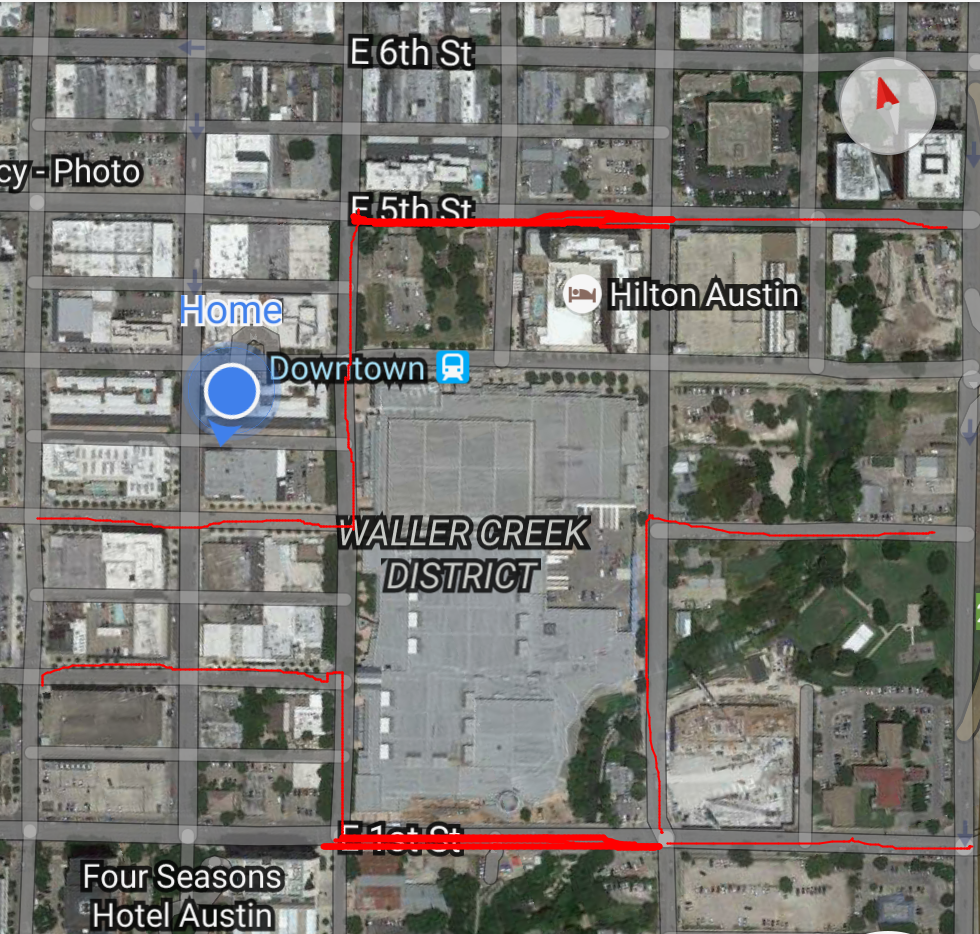

Disappointingly, the plans as written did a very poor job of imagining not just how the outside world could be reshaped to benefit the convention center, but how the convention center could be reshaped to take its place in the city. Downtown belongs to no one industry, group, or activity. Our zoning, unlike most other areas in the city, allows a vast array of uses, from hotels to apartments, offices to bars, parks to shelters, all next to one another. Within blocks of the Convention Center, there are already many different planning efforts underway. The Waller Creek Conservancy is leading the development of a grand new linear park along Waller Creek. (The creek itself is adjacent to the Convention Center.) A transportation planning study for the Rainey St area (a difficult pedestrian crossing across Cesar Chavez from the convention center) was recently completed.

In the vision that the Task Force put forward, we recognized this and took a few steps: 1) we recommended that City Council put out a Request For Information (which would typically lead to a Request for Proposal) on designs for this area; 2) we recommended that improvements to the immediate vicinity of the Convention Center area (a category of expenditure allowed when improving a Convention Center) be coordinated with other planning efforts in the area, such as the Waller Creek Conservancy. 3) We recommended examining the possibility of extending the Waller Creek TIF to use tax revenues from new development toward urgent social priorities downtown.

What still needs to be done

Given the big changes coming out of the Task Force and the fluid nature of the project, now is the perfect time for people to be thinking big. What could be done in this corner of downtown to make this place the best it can be for tourists and Austinites alike? We are too early for public input on the question: the Task Force has agreed to but not yet released its report; the City Council has not yet heard it, let alone taken action on it. But we’re never too early for a good brainstorm.

6 reasons to be skeptical of pouring more money into the convention center

The Austin Convention Center is considering expanding to another 3 blocks downtown. Here’s 6 reasons to be skeptical:

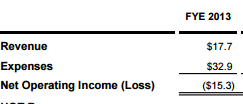

1. The Convention Center Loses An amazing Amount of Money

Even though the convention center doesn’t pay rent like a normal business, it loses stacks and stacks of money: $15.3m in 2013. It takes skills to run a business well enough to pay downtown rents. It takes special skills to run a rent-free business downtown and lose twice as much money as you make!

Even though the convention center doesn’t pay rent like a normal business, it loses stacks and stacks of money: $15.3m in 2013. It takes skills to run a business well enough to pay downtown rents. It takes special skills to run a rent-free business downtown and lose twice as much money as you make!

2. The Convention Center Taxes Every Visitor to Austin To Subsidize Their Customers

The only way the Convention Center can balance its budget is to take the lion’s share of the city’s $9 tax on every $100 that every single tourist spends on hotels in Austin–whether they’re in the very small minority here for a convention or the vast majority here to listen to music, visit family, do business, go to Lake Austin, watch a UT game, or any other reason! A case can certainly be made that we should tax visitors to pay for things many visitors want but don’t make much money–parks, music, arts, museums. But we spend the vast majority of our tourist taxes on just one thing–the convention center.

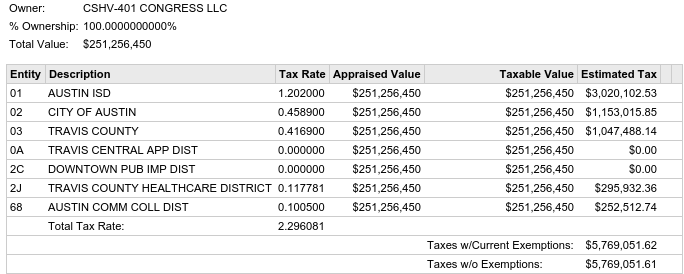

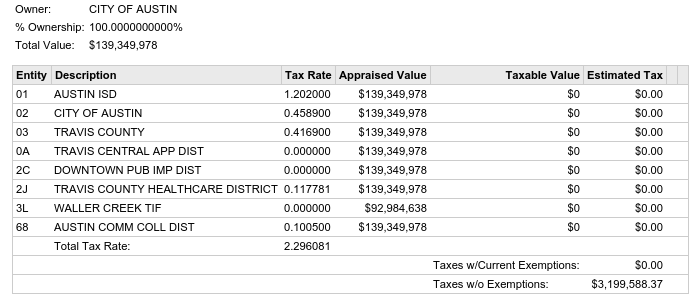

3. The Convention Center Is a Giant Tax Dodge

Unlike the Convention Center, most downtown buildings pay huge sums on property taxes:

- 100 Congress: $3.69m

- JW Marriott convention facilities/hotel: $5.24m

- Frost Tower: $5.77m

- Austonian: A lot! But harder to calculate.

- 6-block convention center: $0.

If the Convention Center takes even more blocks off of the tax rolls, that could pull millions more dollars in potential taxes away from the city, the county, and Austin schools. That’s a property tax break EVERY SINGLE YEAR that we will be using to subsidize the convention industry.

If the Convention Center takes even more blocks off of the tax rolls, that could pull millions more dollars in potential taxes away from the city, the county, and Austin schools. That’s a property tax break EVERY SINGLE YEAR that we will be using to subsidize the convention industry.

4. The Convention Center Economic Analysis is Really weak

When people come to conventions, they spend money at hotels, bars, and restaurants. That’s good–it puts people to work and generates tax dollars. But downtown condo dwellers and office workers not only spend money on lunch and cocktails, they also spend money on legal services and dentists and furniture and everything else, not to mention taxes that pay for schools and streets and parks. Is the economic activity generated by conventions more than that generated by other uses? Enough more to justify giving tax incentives? Do we lose any non-convention tourism business because of the costs of our hotel taxes? Are there better uses for our tourist taxes than more convention center? The analysis doesn’t even ask these questions, let alone try to answer them. C’mon guys! You’re asking City Council and taxpayers to invest $400m in a money-losing business and your business case doesn’t answer the most basic questions.

5. The Convention Center Screws up traffic

Most buildings downtown are pretty small and reserve their disruptive traffic (trash collection, loading/unloading) for alleys. Some buildings, like the W or the JW Marriott, take up a full city block, which forces disruptive traffic into the street itself. The Convention Center one-ups even these buildings by shutting down 7 combined blocks of 2nd St, 3rd St, and Neches, forcing all nearby traffic onto crowded streets like Cesar Chavez, 4th, 5th, Trinity, and Red River. Like channelized water with nowhere else to go, traffic on Cesar Chavez regularly floods. The new plan mostly envisions keeping Trinity open; it needs to go much further to keep all existing streets open.

6. The Convention Center is a bad neighbor

Most developers downtown don’t just make a nice new building, they spruce up the area around them a bit too. The Independent condo tower is extending out the Shoal Creek Trail and building a pedestrian bridge. The 70 Rainey apartments are fixing up a park on the lot next door to them and building a wall covered in plants so neighbors have something pleasant to look at. The Convention Center has built one of the ugliest walls in all of downtown, helping to make Palm Park one of the most unloved and forgotten parks in the city. They say they’ve learned their lesson and they want to make the expanded section better. It would be a lot easier to believe them if they cleaned up their act first and put some real money toward fixing up Waller Creek and Palm Park and maybe trying to figure out some way to undo the ugliness of their current building. (Full disclosure: I’m affiliated with the awesome Generation Waller, but I’m speaking for myself.)

So, basically, you hate this expansion plan?

Really, not as much as this article makes it seem. But if the convention center authority wants us to believe their goal is improving the city, not securing their budget, they need to seriously step it up:

- ACVB says demand for conventions is so high, they’re turning conventions away. If so, they should be able to raise prices and stop bleeding so much money. If they can’t even raise prices on a money-losing enterprise, we should really question the whole idea of expansion.

- ACVB says they’ve learned design lessons from the terrible mauseoleum approach to building a dead building and destroying downtown street life. Prove it! Put real design sense and money into fixing the existing building first to show you now know what you’re doing. Improvements on the south side are a great start; now address the gaping holes on the east side.

- ACVB should be a good neighbor! Put more money into fixing up Waller Creek and Palm Park, following the Waller Creek Conservancy vision. Put more money back into the music community, one of the major selling points of Austin as a tourism and convention destination. Promoting Austin as a city should be about more than exhibit spaces and hotel room counts. It should be about keeping Austin a place that people want to be!

When the convention center was expanded in 2002, the world was a very different place. Downtown was filled with many low-value, low-intensity uses like surface parking lots and auto lots. One more low-slung ugly building fit in just fine. But now, the city is not approaching the convention center hat in hand desperately looking for jobs and downtown activity. The alternative to a convention center expansion isn’t a dead downtown; it’s a downtown Austin that continues to be one of the most prosperous, livable, desirable places to be in the entire state of Texas, radiating tax dollars out to fund the city. The Convention Center needs to understand this and improve their offer.

In addition, the days when the public was happy to give tax incentives to big businesses to get new jobs are over. Unemployment is scraping bottom in the city of Austin and City Council is rejecting hotel jobs (like the East Cesar Chavez hotel) even when they aren’t subsidized. Multiple bonds for 9-figure public projects like this one have been rejected by the public, for better or worse. An expansion plan that looks like a solid business plan for a money-making business will look an awful lot better to the incentives-wary Council members and public than red ink forever on an ever-growing budget.

2014 in Downtown, in Words and Pictures

2014 was a big year for downtown Austin. Major themes as I see them: