Last post, I talked about physical alternatives that would let us #parktheplinth. Or in normal terms, ways to build downtown towers that don’t have giant parking plinths. Before that, I also discussed the regulatory reasons why large parking plinths are common downtown, but much less so in West Campus. So, today, let’s combine the two thoughts: what regulations could we have downtown that would encourage people building towers downtown to use some of those alternatives to parking plinths?

parking

Five Alternatives to Giant Parking Plinths

Last year, I sketched out why downtown has so many huge parking plinths. But another world is possible! Today, we’ll check out alternatives to the plinth. Then, coming soon, we’ll have a look at how regulations could finally #parktheplinth.

How West 6th Was Accidentally Fixed for the Age of Scooters (and How to Keep it Fixed)

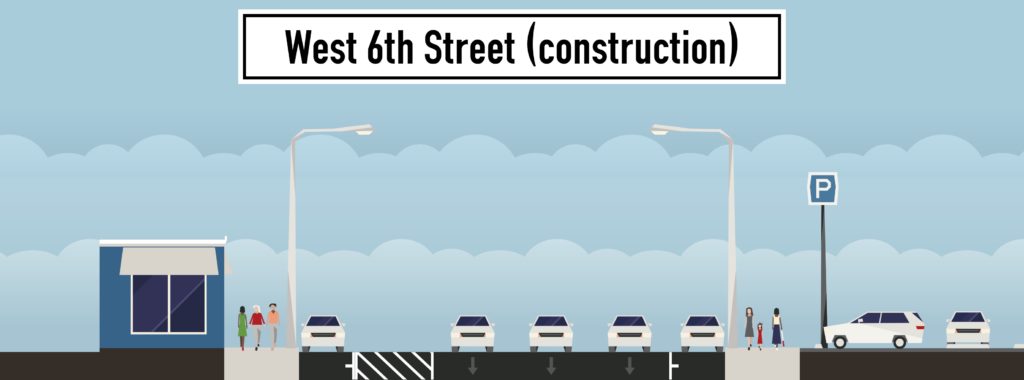

There’s a new development on West 6th Street downtown. A six-story hotel going by the name “Canopy By Hilton” is being built next to Star Bar, between Nueces and Rio Grande (details at Towers). Space being rather constrained next to the hotel site, the developers have rented space to stage demolition and construction on the street itself, temporarily narrowing 6th Street:

For the last week, West 6th St has been narrowed between San Antonio and Rio Grande to make room for construction of a hotel. As a result, the street feels much safer. @austinmobility, let's make it permanent. pic.twitter.com/Tllk7FzzAQ

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) September 18, 2018

Here’s what 6th Street looked like pre-construction from the perspective of the Google Maps street view car:

Let’s take that and simplify it a little in StreetMix:

Now, let’s look at what it looks like today:

Let’s simplify that in StreetMix again:

A funny thing happened on my walk home recently. I noticed that there were no cars parked in the parking spots on the left hand side of this picture and a number of people were using it to scoot in. The blocked-off lane was functioning as a buffer between the scooters and car traffic, thus creating a temporary protected lane.

If the city kept this configuration but made it slightly more permanent, here’s what it might look like in StreetMix:

I’ve replaced the car parking on the left with a two-way bike/scooter lane and updated the buffer so that people can use it to park scooters. Also, I threw in some potted plants as buffers to discourage people from using the buffer, by accident or impatience. The buffered area could not only fit scooter and bike parking, but it could do so and still leave room for a few taxi/Lyft pullouts. Is this the ideal configuration of West 6th? No; I definitely think a professional street designer could do better. But it shows how even a very low-dollar intervention could simultaneously remove some of the many annoying and at times dangerous conflicts on downtown streets:

- Conflicts between people riding scooters and people driving cars

- Conflicts between people riding scooters and people walking on sidewalks

- Conflicts between people parking scooters and people walking on sidewalks

- Conflicts between people getting picked up or dropped off in Uber/Lyft cars and people driving cars, scooters, or bikes.

Of course, just because this configuration wouldn’t cost much money to execute, it doesn’t mean there aren’t non-financial costs:

- 13 meter spaces are removed from the street, forcing more drivers to pay market rates to park their cars in parking lots or garages.

- One car-sized lane has been removed from the street, reducing the peak capacity and slowing the time it takes for drivers to get from downtown to Mopac at rush hour.

Conveniently, Austin has more parking downtown than it has land downtown. (This is true because parking spaces are largely stacked on top of one another).

The amount of parking in Downtown Austin is equal to one surface lot larger than Edwin Waller's original city plan. pic.twitter.com/1HE8bbCcTy

— Caleb Alan Pritchardo (@cubbie9000) May 14, 2018

So, the question becomes not one of finance but one of values and vision. Are we a city that values safe, convenient streets for walking, biking, and scooting, as well as driving, or are we a city that can’t wait the additional two minutes to get on Mopac?

Does transportation serve people or do people serve transportation?

No big city has solved either of two problems: making car traffic flow smoothly or making parking simple and cheap. The issue isn’t that governments in every city are bad, though sometimes they are, or that traffic engineers didn’t anticipate the future, though sometimes they didn’t, or that drivers drive too aggressively, though sometimes they do. The issue is that these problems are impossible to solve due to basic geometry. You can fit more people close together than you can fit cars close together. In a small town, you can fit all the people and the cars together without much difficulty. But as a city grows larger, it’s easier to accommodate people, which are relatively small, compared to cars, which are relatively large.

There are a million ways to think about this that all come to the same conclusion. Caleb Pritchard has pointed out that there is more space downtown devoted to parking cars in downtown Austin than there is space in all of downtown (some of the parking spaces, of course, are stacked in multi-level garages, so the math works):

The amount of parking in Downtown Austin is equal to one surface lot larger than Edwin Waller's original city plan. pic.twitter.com/1HE8bbCcTy

— Caleb Alan Pritchardo (@cubbie9000) May 14, 2018

New office buildings in Austin devote as much space to storing cars as they do to storing people.

Glass on 500 W 2nd gives a nice illustration of the building's split into car floors (unlighted, bottom) and person floors (lighted, top) pic.twitter.com/QeyZMSTa89

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) February 21, 2018

This is ugly and wasteful and terrible for the environment and extraordinarily expensive. It requires people to spend a long time and sometimes a lot of money circling up floors or circling city streets to find parking spaces and people hate the process with a fiery passion. People’s (un)willingness to circle up floors to park is the binding factor limiting the size and creativity of downtown office buildings in Austin. Car parking is the reason our office buildings are shorter than our residential towers — illustrated nicely by how the Sullivan’s Tower got shorter when it was converted from apartments to office. Car parking is also the reason our office towers are shorter than office buildings in less car-oriented cities like, say, New York or Houston. But despite all that, it kind of works. Every work day, 100,000 people find a place to store 2,000 lbs of metal within a square mile of land, so that they can be close enough together to hold a meeting in the conference room or walk to the courthouse or the state house or the post office or city hall or each other’s offices or any other places they need to go as part of their work day.

As bad as the parking situation can get, it’s good news compared to figuring out the logistics of moving them around the city. We can make many more multilevel parking garages in downtown Austin before we run out of space, but stacking cars on top of one another when they’re driving (by building tunnels or elevated streets) is prohibitively expensive for more than a few major highways. Even then, the best you can hope for is two or maybe three levels that people hate to drive on, look at, or live near. You can widen streets to handle more cars, but the more space you use for streets, the less space you have for the places people are using those streets to go.

Another option is to spread buildings out. Instead of a huge chunk of people coming together to work downtown, make many different employment nodes around the city. This can work, to some degree. But the reasons people needed to be in close proximity to one another don’t go away, so the cure is often worse than the problem. Instead of finding a way to get people who need to be in proximity with one another into a small walkable area, you require them to drive half an hour to get to any meeting they have, creating even more traffic and making things even worse!

There’s simply no solution that allows people to get wherever they want in a big city in a car without facing traffic along the way. Implicitly, when we develop new buildings, our development rules recognize this fact. New buildings are required to perform a “Traffic Impact Analysis” which uses arcane, inaccurate, and context-free rules to model how many times per day somebody will arrive at or leave a building, depending on what kind of things people do inside the building. Rules which require a TIA often limit the number of so-called “trips generated” for a particular development.

Why do we say medical offices "generate trips?" Medical need generates trips. Medical offices meet those needs. Same for all types of trips.

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) July 15, 2016

The basic idea behind trip generation limits is the understanding that big cities and cars are fundamentally incompatible. Rather than limiting the use of cars, limits on “trips generated” are a vain attempt to limit a city from growing too large to outgrow the usefulness of cars. The reason why this attempt is in vain should be apparent: trips aren’t generated by buildings, but by needs. Sprawling trips out over a bigger area merely forces people to drive even further, creating even more traffic.

Of course, just because cars and big cities have fundamental conflicts doesn’t mean cities can’t continue to outgrow the constraints of car-oriented development. There are countless solutions: buses, trains, bikes, scooters, sidewalks, dollar vans, etc. The details of each solution vary but the overarching idea is very similar: 1) make trips shorter so people don’t need to travel as far to get to the places they want and need to go, and 2) fit people closer together while they’re making trips to make more efficient use of each street.

Hint: pic.twitter.com/R4NM8IFb0A

— Caleb Alan Pritchardo (@cubbie9000) May 17, 2018

There have been some positive ideas on reforming TIAs to use these solutions, California being the best example in the US. But I’d like to propose a different way of thinking what a TIA could be. Instead of assuming cities are tied to cars only and then limiting developments to the constraints that cars have, we could start with the development we want and then require that this developments accommodate whatever transportation system is necessary to complement it. Instead of trying and failing to scale cars to a level that they simply aren’t capable of handling, we find the transportation system that is actually capable of handling the development.

For example, if a developer proposes a development whose size or density tips past the point where most trips can be comfortably done with cars, she would be responsible for providing street designs that include different ways of getting around: bike lanes and bike corrals, or designated places to store dockless scooters, or proximity to a transit line.

There is a sense in which we do this already. Austin’s land development code, like many others, requires infrastructure for cars (mostly parking) but allows developers to provide less of it if they provide alternative transportation infrastructure (e.g. parking spaces designated for shared cars like Car2Go, showers for bicyclists). But these efforts are piecemeal and complicated. All too often, TIAs are wielded as weapons to prevent homes and offices, when instead, we could make them a tool to make any development work.

6 things to like in California’s proposed transit housing law, illustrated by surfing

On January 4, California felt two earthquakes. The first was a conventional and thankfully weak earthquake in Berkeley:

The Did You Feel It? survey form for the Berkeley, CA M4.4 EQ is back up and running: https://t.co/jY2poBayEX Please tell us what you felt. pic.twitter.com/OVb8r4p22q

— USGS (@USGS) January 4, 2018

The second was a political earthquake, emanating from across the bay in San Francisco:

I’m introducing an aggressive housing legislative package: 1) require denser/taller zoning near public transit, 2) require cities’ housing goals be based on actual future growth & make up for past deficits, & 3) make it easier to build farmworker housing. https://t.co/YLQ9djH5pN

— Senator Scott Wiener (@Scott_Wiener) January 4, 2018

So, here are six things to like about the transit-oriented development bill that’s making waves in state politics:

1 It acknowledges the state has an interest in land use

Many decisions are better made by cities than states. Where will the next branch library go? Should this park have a splash pad or a lawn? But some problems are too big for one city alone, like intercity transportation. If Austin and San Antonio decide to be connected by a train, Buda, Kyle, San Marcos, or New Braunfels should have input (as the train would go through these cities), but they shouldn’t be given a flat veto. It is up to the state government to help manage this process so that local interests in one city don’t hurt local interests everywhere else.

In California and some other states, housing and land use have become problems with statewide and national implications. Housing prices aren’t just high in San Francisco or Los Angeles or even Berkeley; people unable to find housing in those cities are spilling over to suburbs and exurbs all across the state. Whole companies are looking to other states to set up offices because their workers can’t afford California rents. The greenhouse gases from long commutes affect every person on the planet. When a problem is widespread, the solution needs to be widespread too; cities rules by local interests just doesn’t cut it.

2 It creates fair and impartial rules

Laws made at the local level can take into account local context better than statewide rules can be. But laws made at the state level can better take into account the statewide context. In a drought, we need fair rules so that everybody does their part to conserve water and everybody has access to the water they need. In a statewide housing drought, we need fair rules so that everybody does their part to build housing.

3 It forges a link between transit and density

In the sphere of YIMBY and placemaking, the problem in California is a very YIMBYish problem: there aren’t enough homes to go around for all the people who want to live in California’s cities. But the solution that Wiener proposes isn’t just focused on getting people into homes anywhere. By proposing rules for allowing more homes near transit, it creates the chance for cities to use this as an opportunity to make great places for the future, where high-capacity transportation solutions are matched with high-capacity housing solutions.

4 It acknowledges how parking rules can hurt housing

One type of land use rule that’s particularly pernicious is the minimum parking regulation. These rules not only incentivize car use by forcing everybody to pay the price of car storage whether they drive or not, they also cut into the budget (both financially and physically) of new housing. This legislation will stop cities from using these pernicious rules near transit stops and opens the possibility for people to find new ways to live cheaper while using less parking.

5 It helps bridge the gap between people and jobs

The problems of California’s cities aren’t their problems alone. Vast swathes of the state are home to unique industries, from Silicon Valley’s tech economy to Hollywood’s movie industry. Sure, tech jobs exists outside Silicon Valley and movies are filmed all over the world. But place has, if anything, grown more important over the last decades, not less. Young workers looking to break into an industry would do well to show up where the jobs are, and new companies looking to start up would do well to show up where the workers are. Today, though, many people are shut out of these engines of prosperity because they can’t afford to live in Palo Alto, San Francisco, or Los Angeles while they lean the trade. Who knows what great technology or film talent we may cherish tomorrow if only we make room for them today?

6 It might just save humanity

With the United States federal government oriented away from action against climate change, individual states badly need to step up their game. While trying not to overstate the importance of this bill, the fate of the entire human race might depends on our ability to transition the United States and our high-emission society into one in which we can get around more efficiently.

So congratulations to Senator Scott Wiener! You brought a proposal that deals with the scale of the problems your state and this country are experiencing, and you may have changed the conversation on housing for good.

Words by Dan Keshet. Gif selection by Susan Somers.

The one little rule that decides where Austin’s towers build parking

Not every tower in downtown Austin looks exactly the same, but there is one defining characteristic that describes almost all of them: parking. Most towers rest on top of what they call in the industry a parking plinth, the tower base where folks store their cars. (Plinth is a Swedish word meaning ugly thing.) Here’s a typical example, the Seaholm Tower in southwest downtown.

On the ground floor, there’s a restaurant. Above that, the area with small and sporadic windows is the parking garage. Above that, the area with balconies is where the condos live. Simple, effective, but not always super sightly, at least to my tastes. Why not build parking underground, freeing up aboveground levels for more homes? For one thing, building underground car parking is very expensive. The exact difference varies by site but I’ve seen estimates that moving a parking space underground can add $10K to the cost of the space — and the further you have to dig, the more expensive it gets. So perhaps underground parking is reserved for the most expensive buildings?

No, even in Austin’s newest luxury towers you see aboveground parking:

Parking underground is just too expensive for Austin, or so I thought, until Sid Kapur pointed out to me that there is somewhere in Austin building underground parking:

[tweet 938849429121060865]

Yes, of course, West Campus (aka Bizarro Austin) is building underground parking. See James Rambin’s writeup at sister site Austin Towers of projects like Skyloft and Aspen West Campus with four stories of underground parking. So why do developers building student housing decide to put parking underground? Are students more discerning aesthetic connoisseurs? Sorry, students, but I doubt it. I have an alternate theory.

There are many different ways that zoning codes can limit the amount of space that can be built. In downtown, the binding constraint preventing even larger buildings is something called Floor Area Ratio or FAR: roughly, the square footage of climate-controlled space in a building divided by its footprint. In West Campus, the binding constraint on the size of a building is regulations on maximum height. Crucially, parking counts toward a building’s height but doesn’t count toward its FAR. If a developer in West Campus moved their parking from below-ground to above-ground, they would have to remove apartments in order to fit it in, costing them a lot of money in lost rent. Developers downtown, though, don’t have a height limit so building a parking plinth costs less than putting parking underground, doesn’t use up the building’s FAR, and even makes the residential units more valuable by giving them better views.

If my theory is true, it makes some predictions: portions of northern downtown that are slated to be rezoned with height-constrained zoning categories (CC-40 and CC-60) will likely see underground parking, while the FAR-constrained central business district will continue to see parking plinths. Indeed, the condo building I live in downtown was built pre-CodeNEXT but it had height limits imposed as part of the rezoning process and consequently built most of its parking underground:

8 reasons to End West Campus Minimum Parking Rules

In West Campus, as in all of Austin outside downtown, there are rules that require new homes and shops to build new parking spaces. Minimum parking rules don’t make a lot of sense for the city in general but make even less sense in West Campus. Here’s 8 reasons those rules should be repealed:

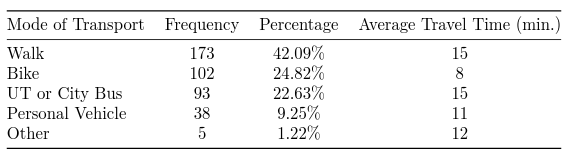

1. Most west campus residents walk, bike, or bus to campus

Austin is car-centric. But in the last 10 years since we have allowed dense, mixed-use buildings in West Campus, it has become the shining exception. Only 9% of grad students living in West Campus use their cars as their primary means of commuting!

2. land used for cars is land that can’t be used for homes

Obvious but needs to be said! Tons of students wish they could live in West Campus and walk to school. Many of them end up living much further from campus. If we took the land that’s currently being dedicated to long-term parking and freed it up for more apartments, more students could live in West Campus and walk to school.

3. Building Parking increases the costs of building new homes

Building parking is expensive! An on-site, off-street parking space can cost up to $40K to build. If we let new apartments be built without parking, it’s doubtful we would see rents come down immediately. But in the long-term, reducing costs is the only way to keep rents down.

4. students choose whether to bring cars

In much of Austin, living with a car is a necessity for living a functional life. In West Campus, though, living without a car is a viable choice for most students. Students take into account the availability, cost, and convenience of parking when deciding whether to bring a car to school. When we force apartments to overbuild parking, we aren’t responding to the reality of students taking cars to school so much as creating that reality!

5. there’s already a lot of parking in West Campus

Will there still be students who need or want cars in West Campus? For sure! Fortunately for them, even in the very unlikely event that all new buildings featured no new parking, most existing buildings do have parking lots or garages. Students who value on-site parking can choose to live in a building that has it.

6. On-street spaces are metered.

Sometimes, people fear that if new apartments don’t build parking, residents will still bring cars but park them on the street. In West Campus, though, streets have parking meters, so students would be better off either buying off-street parking or not bringing a car.

7. Parking garages are ugly

This one is subjective, but overwhelmingly true. West Campus since UNO has seen a bloom of street trees, sidewalks, and interesting new buildings. The ugliest of those buildings? Overwhelmingly the parking garages.

8. It sends a message

Do we live in a society that understands the bigger picture in which auto-centric design is driving our planet into catastrophic climate change? Do we care?

College isn’t just a place to learn facts; it’s a place where we teach the next generation the values that we hold as a society. Right now, our code is teaching a “can’t-do” attitude about building better places and fighting for our environment. We can and must do better.

Residential Permit Parking: for residents to park or so nobody else can?

Residential Permit Parking is ostensibly to allow residents to find street spaces near home in areas where parking is super competitive. In practice, though, few residents park onstreet during restricted hours and most of the parking goes unused.

It’s a phenomenon very easy to spot near the South Congress commercial strip:

Residential permit parking 1-2 blocks from S Congress. This is waaay underutilized. pic.twitter.com/NzomYZ5an7

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) May 11, 2015

But it happens all over the city, wherever we create resident-only zones. Clay Avenue off Burnet:

@DanKeshet Looking north on Clay Ave just north of Houston. RPP says no parking anytime without permit pic.twitter.com/KYTPaHjgtQ

— Mary Pustejovsky 😷 (@mpusto) January 4, 2015

A few blocks west of that, Montview Avenue, also off Burnet:

On Fortview, near Manchaca. Note how the unused parking starts where the residential zone starts.

On Daniel Drive, one street over from Barton Springs Rd:

Some RPP zones in Mueller (all via Mateo Barnstone):

And near South 1st (again via Mateo Barnstone):

Do you have pictures of street parking going largely unused once designated as residents-only? Tag them with #NoParkingInRPP on twitter or add them to the discussion on the Austin on Your Feet facebook page.

If you plan for everyone to drive cars, they will

On June 18, City Council took its first look at an ordinance to make it easier to build granny flats, also known as ADUs or backhouses. A granny flat is a small home on the same lot as a single-family home. They have traditionally been used to keep multi-generational families together or as an affordable option for rental housing. Very few new ones have been built in Austin lately, in part because rules make it hard. But this column isn’t about granny flats. It’s about one comment Council Member Leslie Pool made, about the requirement that each new granny flat be paired with an off-street parking space:

I want to acknowledge that while we’re moving in other transit-oriented directions, which I support, the reality is that people in Austin still drive cars, which is why we have the requirement for at least one [off-street] spot for a car to park.

In the past, CM Pool has showed vision toward what she calls “other transit-oriented directions” by signing AURA’s pledge to make a transit-oriented Austin. So I’d like to challenge her and any others thinking along these lines to think bigger about how they as Councilmembers can shape our city.

Off-Street Parking Doesn’t Just Reflect Our Driving Reality, it Drives Our Reality

Not every new household in Austin must bring or buy a car. I get around without a car and it’s getting easier all the time. But many people will weigh whether to own a car and decide that, as things stand, they’d be better off with one. Some of the people who decide to own a car are actually close to choosing not to have one, but are ultimately swayed by the particulars of their situation.

Our parking requirements are one of the prime reasons driving the decision to own a car:

- Some potential ADUs in older, central neighborhoods, won’t get built because a legal parking space can’t fit on the lot or the homeowner doesn’t want to pave their little paradise to provide a parking space. Potential residents who would’ve chosen to live in an affordable, small, central home are forced to live further on the periphery and drive in.

- Instead of some ADUs being built with a nice garden and no car parking, and others with a small or non-existent garden but a parking space, all will have the parking space. Deprived of the potential benefits of doing without parking, residents may as well make use of the space.

Requiring parking drives the reality of people choosing to own cars. It’s important for policymakers to not just react to life as it is now, but to be move us towards a future where people have the practical freedom to live with whatever transportation mode they choose.

How it works downtown

The city council ended parking requirements downtown a few years ago. The result has not been a parkingpocalypse of car-drivers unable to move downtown because they can’t find parking. Most new projects that have gotten built since then have included parking. This shouldn’t be surprising: downtown is mostly a high-end market and people who can afford to spend a lot of money on housing can afford cars as well. New apartment and condo complexes like Fifth and West, the Seven, or the Bowie include parking as an amenity.

But some projects are getting built with less or no parking. A new office building on Guadalupe was built completely without parking to lower rents; it advertises availability at a garage a couple blocks over. The JW Marriott hotel was built with limited parking. Some employees take public transit in; others park at a leased parking lot a few blocks away. Conference guests are encouraged to take public transit or use spaces at the convention center garage. The Aloft hotel is going to be built using a valet-only model that shifts cars to existing underutilized garages. There’s even rumors of new apartments planned for downtown without parking for a much lower price point than typical downtown living. Even though downtown is the most accessible place to live in the city without a car, the transition has been slow and gentle.

From here to there

If Council Members fear the consequences of allowing ADUS without parking, there are half-measures they could take that would get most of the benefit. One example would be to allow no-parking ADUs only near high-frequency bus lines that can support carless mobility. This would let the city continue to dip its toes into accommodating folks like me who get around without a car, while maintaining the vast majority of the city for guaranteed parking.

Other Policies

ADU parking requirements are really only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to how policy makes it impractical for most people to live in Austin without a car. Off the top of my head, some other ideas:

- Dedicated transit lanes. About half of those who travel down the Drag do so in buses, packed efficiently into only 6% of the vehicles. If one street lane were allocated for buses to zoom by, like the transit priority lanes downtown, this could benefit half of the street’s users in a stroke.

- Mixing uses. The city maintains a fairly rigid separation of residential space from commercial space. This has some advantages, but the disadvantages for people getting around without a car are obvious: they have to go further from their homes to reach convenient places to work, shop, and dine.

- Allow more residents in transit-accessible places. There’s a limited number of places in the city that are already convenient to live without a car: downtown, West Campus, and other inner-city neighborhoods. Building new transit-accessible places is a time-consuming and sometimes expensive process. The simplest way to allow more people the freedom to live without a car is to allow more people to live in the places that are already transit-accessible.

Vision

The reality is, Austin can’t wait until an imagined transit-oriented future before we give more people the practical freedom to choose whether to own a car. We must forge that future for ourselves. Every day that we delay, the hole we’ve dug for ourselves gets bigger. As I write, there are construction crews building subdivisions in District 6 that will be pretty much impossible to live in without a car for decades to come. Other construction crews are spending tax dollars widening MoPac so that the residents of the new subdivisions can drive into downtown. Shouldn’t we also be building places where people who choose to live a transit-oriented life can do so without paying for parking?

Council considering parking management districts for East Austin, Mueller

As Jennifer Curington reports in the Community Impact Newspaper, this Thursday Austin City Council will consider whether to create its first two parking/transportation management districts. PTMDs are arrangements in which the city installs parking meters in an area that needs them and splits the proceeds from operating the meters between the general fund and a fund that is specific to the area in which the meters are installed. They differ from parking benefit districts, another arrangement that the city can create, primarily in who can apply to create one. (There are some folks who believe PTMDs are inferior to PBDs. For their arguments, read the comments section of this post a little while after I post it.)

The main feature of both these programs is that they control parking demand through the use of meters, a practice that first began in Oklahoma City in 1935. Of course, given the opportunity, most people would just as soon not pay for parking as pay for it, but as I discussed here, that can cause serious problems when there are more people who want to park than there are spaces.

The “revenue split” feature of PTMDs (and PBDs) are essentially political features. Just because it would benefit people on the whole to install parking meters doesn’t make it politically easy to create them. Opposition to meters can come from a number of corners, including merchants who believe their customers will no longer come to their store if they can’t park for free, to residents who dislike having parking spaces they have been using for long-term parking converted to short-term parking for those who live outside the neighborhood. By concentrating the benefits of the meters in the same area where these opponents live and work, theory goes that it will be easier politically to create and maintain support for them.

Indeed, in this case, theory appears to be matching up with reality. Two neighborhood associations–the East Cesar Chavez NA and the Guadalupe Association for an Improved Neighborhood–have joined the city in applying for the “East Austin” PTMD. This PTMD (council item here) would be bounded by I-35, Chicon Street, 4th St and 7th St, or roughly speaking, what many people call East 6th. The meters would run during the busy nightlife hours of 6PM-midnight Tuesday through Saturdays; any residents of single-family homes whose homes do not have off-street parking will be provided permits to use on-street spaces free of charge. Some ideas contemplated in the city documents for where the funds may be used include sidewalks, crosswalks, traffic signals, artwork, and ongoing street maintenance.

If these PTMDs turn out well, they may prove an improved template for managing high-demand parking near commercial areas of the city. The parking management solution most commonly in use, the Residential Permit Parking program, has been a failure. The idea behind it in the first place is essentially exclusionary–the entire purpose of the program is to ban people who don’t live very close to an area in which parking is in high-demand from parking there. This is, to put it lightly, a poor use of a city resource (on-street parking). When put in practice, this program has, not surprisingly, had poor results. Many of those streets in which non-locals have been excluded from parking now sit empty, while parkers just park even further from their destination.

@DanKeshet Looking north on Clay Ave just north of Houston. RPP says no parking anytime without permit pic.twitter.com/KYTPaHjgtQ

— Mary Pustejovsky 😷 (@mpusto) January 4, 2015

Perhaps in the future, the city will decide that rather than playing whack-a-mole with people who desire parking, they should simply charge for it, and use the proceeds to improve sidewalks, crosswalks, and the like.