I apologize for the short five-year break in posting! I’ve been keeping busy with a job that now requires me to work during the hours they pay me for, a volunteer gig at Texans for Housing, and a full-time parenting gig. But let it never be said I abandoned you for more than five years, so here goes my list of top Austin urbanist policy targets for 2024!

Unfinished business

City Council has already laid out a ton of plans for 2024. Here are some of the ones I’m most excited for.

HOME Phase 2

Leslie Pool has evolved into the most influential and far-seeing Council Member in quite some time. Her HOME Phase 1 allowed more duplexes and triplexes, rolled back limits on roommates, and fixed a handful of other issues in code. HOME Phase 2 builds on this, allowing more small houses on small lots.

Address the lawsuits

Recently, a Travis County judge decided Texas’ procedural rules should be interpreted differently than they ever have been before or than they are interpreted anywhere else in the country. This oddball logic threw out three city ordinances: one reducing the distance that single-family houses can interfere with other zoning districts, one allowing more apartments near shops, and another allowing more apartments near shops but in a different way.

Fortunately, all of these measures remain popular with the vast majority of Austinites and Council Members so we should be able to jump through whatever hoops the judge says we need to jump through. And, hey, we have a couple years of data on their usage, so we might even be able to improve on them. Thanks Judge!

New business

More and Better Student Housing

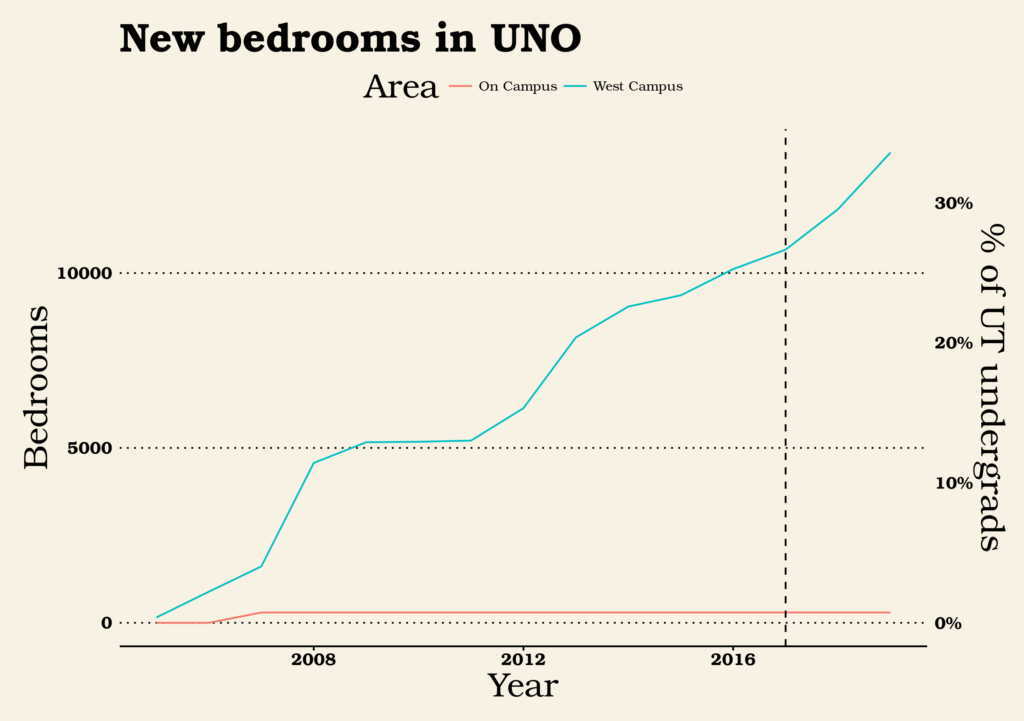

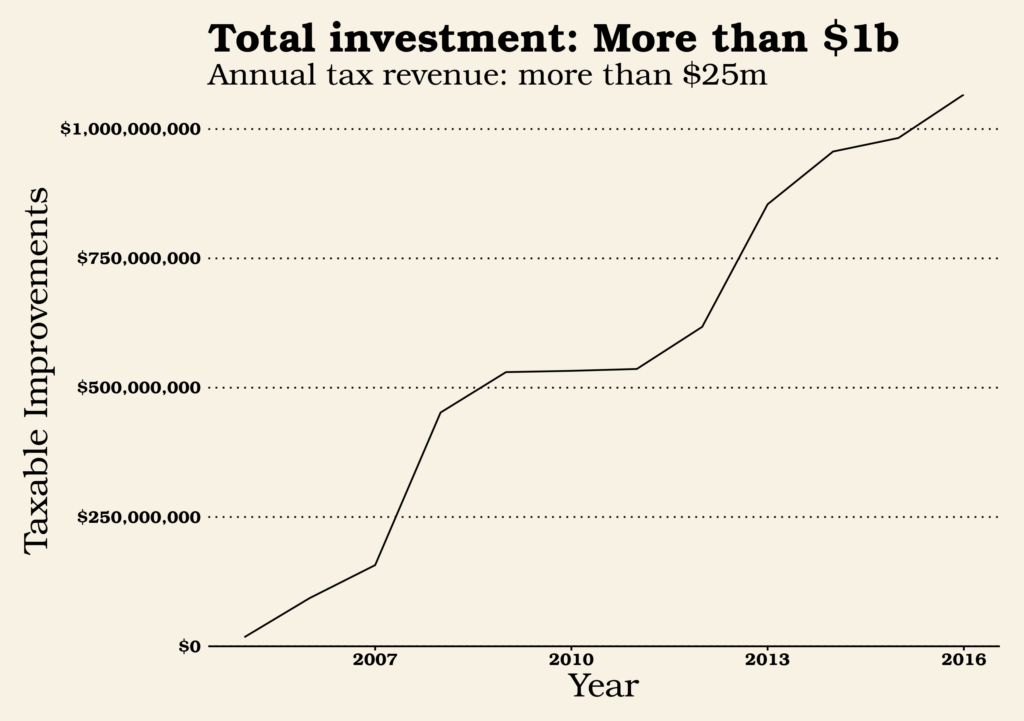

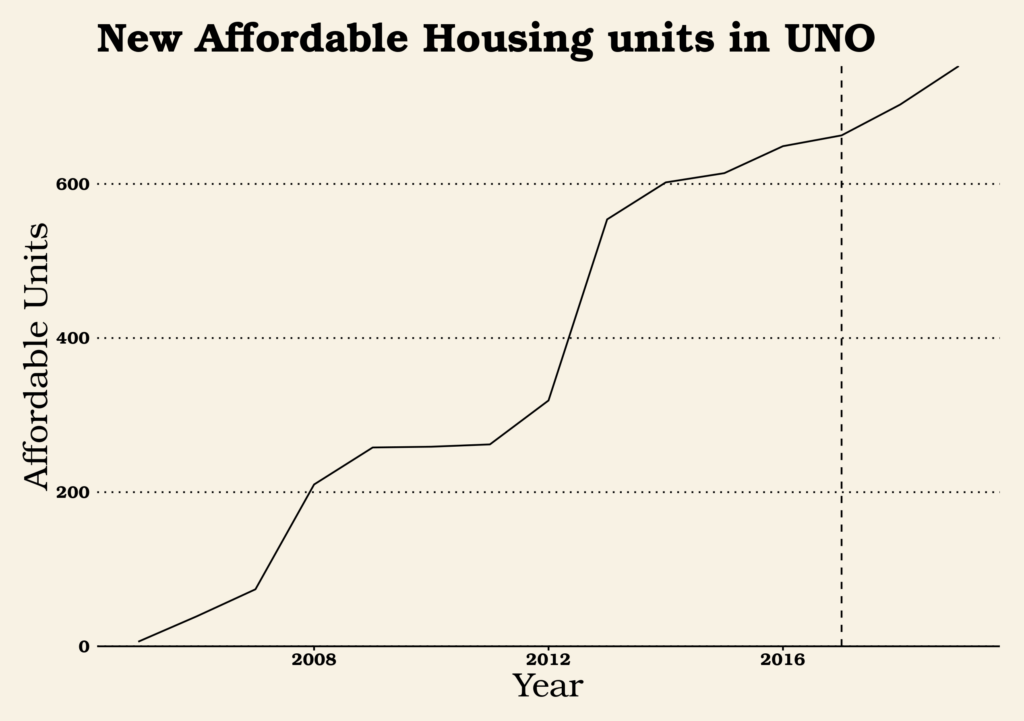

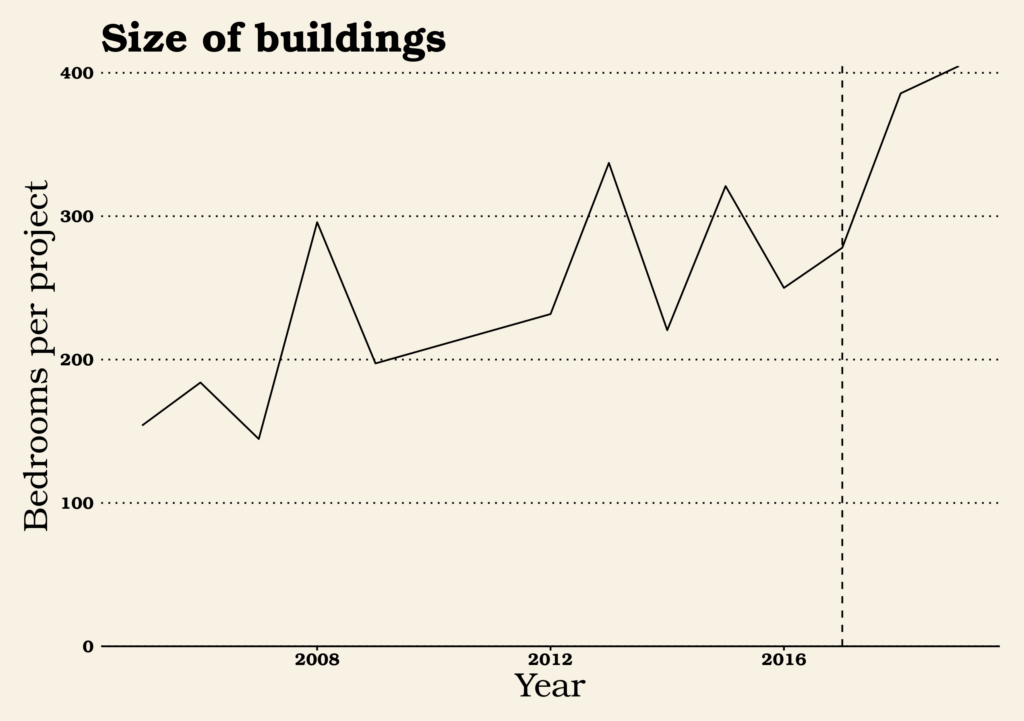

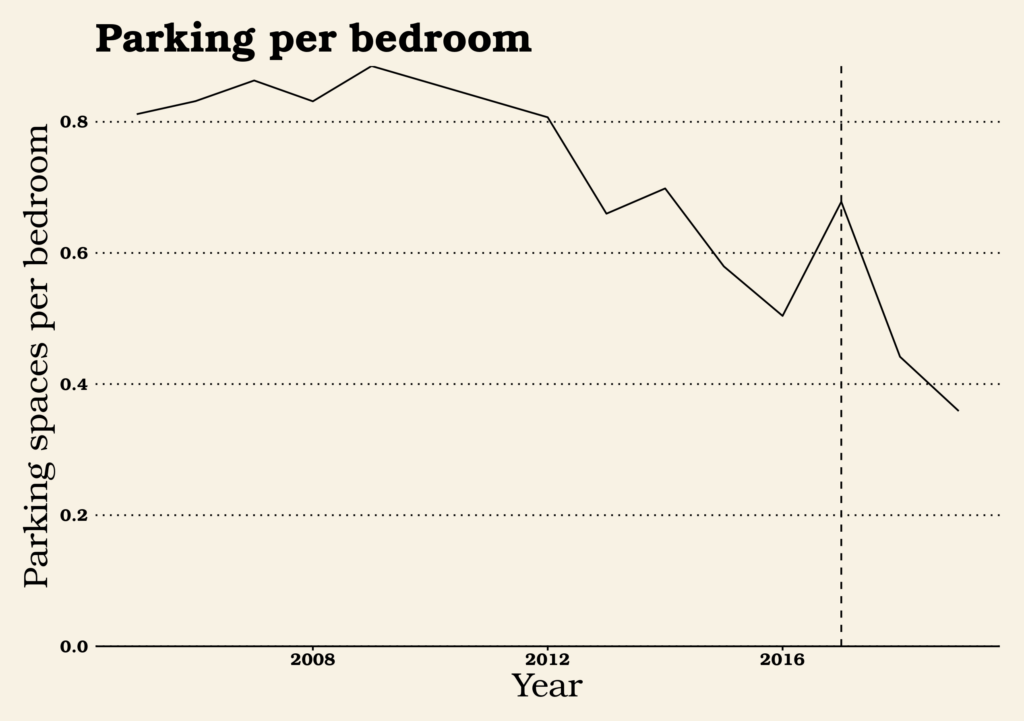

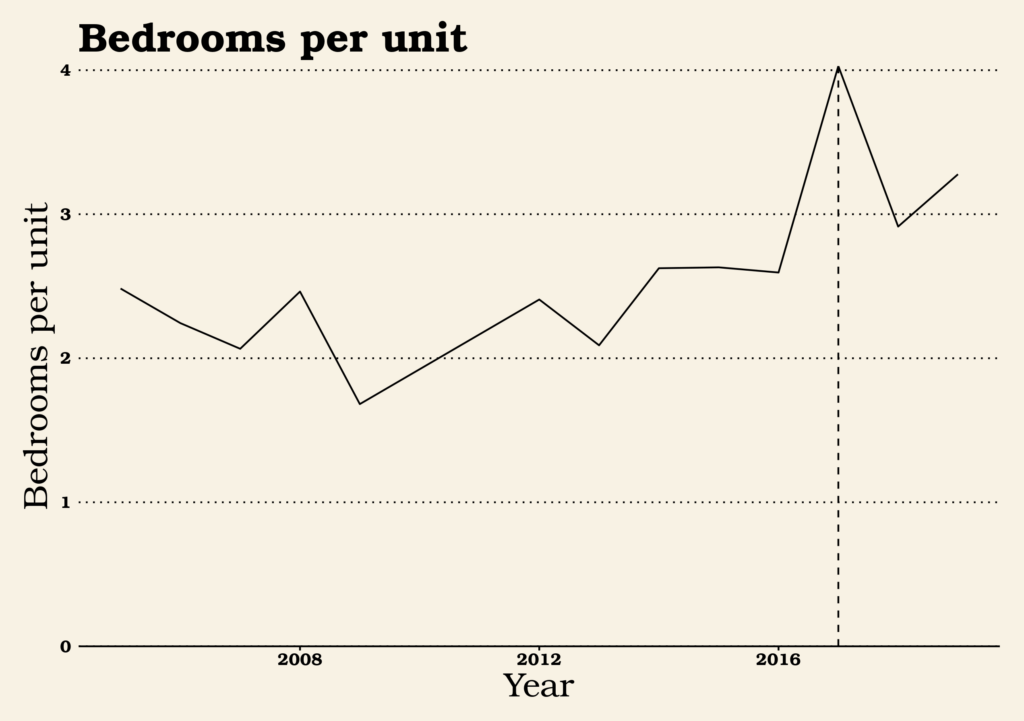

AURA and the University Democrats have drafted a nifty request for City Council to bring the myriad benefits of UNO, Austin’s student housing district, to the rest of the student housing areas in Austin. UNO has been super awesome so building on something that’s already working would be super double awesome. One thing that hasn’t been super awesome in UNO, though, has been that some folks figured out they could build and market rooms without windows to students, many of whom rent their room sight unseen and then find out that windowless bedrooms suck. So let’s fix that while we’re at it.

Bigger -plexes in Central Austin

One of the brilliant pieces of HOME was that, rather than doing artisanal, parcel-by-parcel planning around small pieces of the city, it created rules for the city as a whole. Anybody who wants can build a triplex or two in a standard lot. But everywhere in the city isn’t the same, or else people wouldn’t pay more for a dirt lot in Bouldin than they do for a brand-new house in Circle C.

I’m not particularly fussed if City Council wants to allow, say, 8-plexes on any lot in the city. But lots of people are. So let’s target 8-plexes to the places where dense housing would have the biggest effects, where land costs are highest (and need to be split between more people) and amenities like jobs, shops, parks, and transportation options are plentiful.

Quiet Zones

When we think of zoning, the first thing in many people’s minds is along the lines of “no smokestacks next to houses.” But there’s a lot of distance between “no smokestacks” and “nothing but long-term residences.” And while living near smokestacks isn’t very nice, living near a bakery can be really nice! I would like us to move back toward first principles here, and start reintroducing less disruptive shops and offices near where we live.

Safe Routes for Children

Safe Routes to Schools is a great way of prioritizing sidewalks and bike routes. After all, kids can’t drive, so they’re a captive market for sidewalks and bike lanes. And kids walking or biking to school can fix a huge traffic problem: the school pick-up and drop-off lines. But kids need to go many more places than schools! Libraries, parks, friends’ houses, ballet classes, soccer practice, corner stores, and more! Let’s start thinking about our next steps to make Austin a place any kid can get around without Mommy or Daddy Chauffeur.

Stefan’s Congress Avenue has street maps, a bus lane, bike lane, driving lanes, turning lanes, parking lanes, and sidewalks, capped with a nice row of palm trees down the median.

Stefan’s Congress Avenue has street maps, a bus lane, bike lane, driving lanes, turning lanes, parking lanes, and sidewalks, capped with a nice row of palm trees down the median.

John Dawson of Rocket Electrics has produced a bold vision for a Congress Ave with a wide median sidewalk, bike lanes (presumably including electrics!), and transit on the edge.

John Dawson of Rocket Electrics has produced a bold vision for a Congress Ave with a wide median sidewalk, bike lanes (presumably including electrics!), and transit on the edge.