Susan Somers is a north Austin resident near the North Shoal Creek area, President of urbanist organization AURA, and the genius gif editor who made this blog’s most famous piece pounce.

The city recently released a draft version of the North Shoal Creek Neighborhood Plan. North Shoal Creek is on the far edge of what you might consider north central Austin – bounded by Anderson Lane to the south, Highway 183 to the north, Mopac Boulevard to the west, and Burnet Road to the east. The plan is set to be the first new neighborhood plan in several years and City planning staff seem to have billed it as a kinder, gentler neighborhood plan: one that would try to fulfill the goals of Imagine Austin and identify new opportunities for growth. As such, the draft plan may give us a decent sense of what small area planning would look like if we continue churning out neighborhood plans in the CodeNEXT era.

How does the draft North Shoal Creek plan stack up?

Five things we like

- The plan acknowledges the reality that apartments are more affordable and single family homes are not. The plan repeatedly points out that the apartments and multifamily condominiums in the neighborhood are more affordable that the single family homes. What’s more, “Apartments and condominiums in North Shoal Creek provide more affordable options relative to much of Austin, while single-family homes are less affordable than the citywide average.” It also acknowledges that the majority of people in the planning area live not in the single family homes of the “Residential Core,” but in apartments along the edges of the neighborhood. Furthermore, it points out that the neighborhood’s residents are aging, and young families are being priced out.

- The plan prioritizes walkability. Almost half the “needs” and “values” identified by the community involved walkability in some way. The plan calls for new sidewalks and trails, better access to transit stops, and improved safety for schoolchildren walking to Pillow Elementary. It even contemplates innovative ideas such as opening up a pedestrian trail to access Anderson Lane businesses or allowing the community better access to Shoal Creek.

Hundreds of people live here, but this is not a place that invites walking. Image via Google Maps. - The plan allows homes on the neighborhood corridors. The plan acknowledges that retail, particularly along Burnet Road, is dying. It allows for mixed-use development including apartment homes to be built along Burnet Road and Anderson Lane, the neighborhood’s major corridors. It also acknowledges that transit access is a very important reason to allow these homes to be built, and that apartment density should be clustered near transit. While allowing apartments on transit corridors may seem obvious, North Shoal Creek has fought apartment homes in the past, so this is a promising development.

- The plan supports granny flats (aka “accessory dwelling units”). The plan seems to support allowing homeowners to build granny flats throughout the single family section of the neighborhood. Adding another home to a lot is an easy, almost invisible way to add more housing!

- The plan envisions an innovative “Buell District.” Buell Avenue is currently dotted with light industrial development like self-storage facilities and auto-repair shops. The plan envisions change along Buell Avenue, including special zoning opportunities like townhouses, small apartments, and live-work spaces that would allow a greater variety of housing into the neighborhood.

Five things to improve

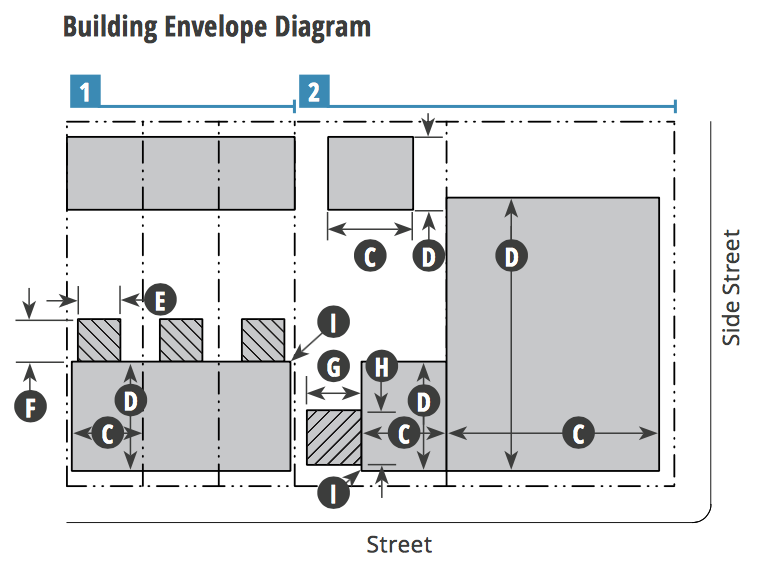

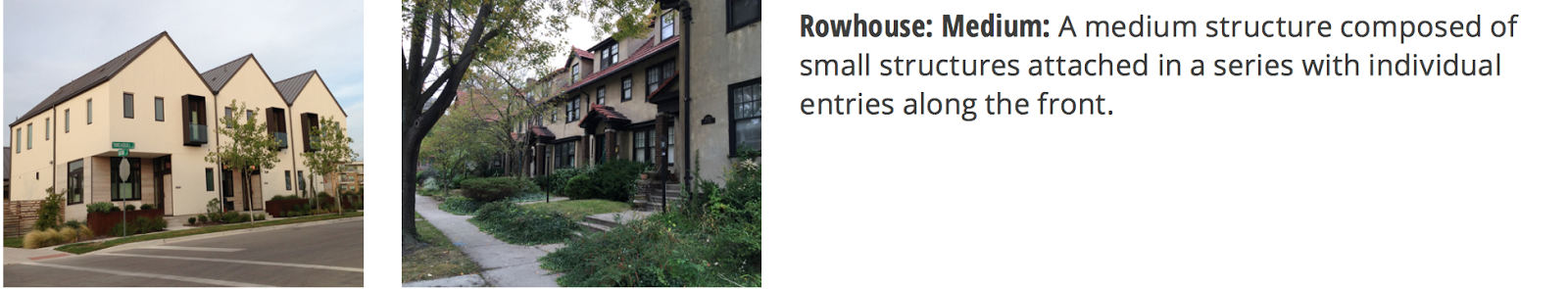

- Choose some side streets for rowhouses. Other than on Buell Avenue, the plan does not call for allowing missing middle housing types like rowhouses on any side streets. We’ve previously argued rowhouses are an underappreciated and underused housing form in Austin, and CodeNEXT should allow more of them. But over and over again, our planning processes shy away from this awesome type of home. There are plenty of larger neighborhood streets in North Shoal Creek that would be appropriate for rowhouses. The plan leaves the impression that the only reason townhouses would be allowed on Buell is that the neighborhood likes the current light industrial businesses even less than they like rowhouses.

Rowhouses are a residential type of building and, as such, they belong every bit as much in residential-only areas as areas of mixed use. - Multiplexes or small apartments on corner lots. Similarly, other missing middle housing types like multiplexes, small apartments, or cottage courts, are not placed in the “Residential Core,” even on large corner lots. Large corner lots are the perfect place to allow this kind of missing middle.

This fourplex is one of the last standing of a formerly common missing middle housing type in residential Austin. - Sanctity of the “Residential Core.” Let’s talk more about that “Residential Core” phrase. As we note above, the plan acknowledges that the majority of residents live not in the interior of the neighborhood in single family homes, but in apartments on the edges of the neighborhood. Thus, calling the single family section of the neighborhood residential as compared to the corridors is a kind of double speak. Literally, more residents live outside the area termed “residential” in this plan! Based on the plan’s constraints, that pattern will become even more pronounced! Why does this terminology matter? Many other aspects of the plan focus strictly on the “Residential Core.” Three of the six bullet points regarding the goals of the Neighborhood Transition area focus not on making the zone great for its residents but on how not to encroach on the privacy of single family homes. The poorer majority residents are treated as interlopers on the richer minority. In fact, it’s not even clear that the existing apartments in the Neighborhood Transition lots would fit the constraints of the plan.

- Vision for connectivity/reconnecting streets. Residents in North Shoal Creek have asked for a more walkable neighborhood and for better access to transit stops. One way to make this area, designed with meandering streets and suburban cul-de-sacs, more walkable would be to designate opportunities to acquire lots and reconnect streets separating people from one another. While the plan considers this for connecting homes to retail via urban trails, there are no such connections proposed in the “Residential Core.”

Google Maps recommends a 17 minute walk along a freeway to walk between these backyard neighbors. - Tying desired neighborhood amenities (sidewalks, parks) to opportunities for density. There are many ambitious, desirable aspects of the plan that are unfunded mandates. These unfunded plans include building out the sidewalk network, adding urban trails, developing more parkland, and creating the Shoal Creek trail. The plan acknowledges the challenges of getting funding to make these a reality. But other neighborhoods where these improvements have actually taken place (like Bizarro Austin) have done more than make a wishlist and hope. They created incentives for redevelopment to happen and required developers to fund improvements to the public sphere as part of that redevelopment.

In some ways, the North Shoal Creek draft plan lives up to its kinder, gentler billing. It recognizes the real problems the neighborhood has: from families being priced out to unwalkability impinging on quality of life. The plan promotes the two main fixes we’ve also seen coming out of the latest draft of CodeNEXT: accessory dwelling units and apartment homes on transit corridors. Let us acknowledge that many of Austin’s older neighborhood plans don’t go even this far. However, to truly confront the problems the plan identifies, broader changes are needed, including in areas where the minority of neighborhood residents live. By opening up to a bit more change, some of the truly visionary elements of the plan could be funded and constructed.

He believed that any food in the apartment was, by rights, his.

He believed that any food in the apartment was, by rights, his.

He realized the problem: he was taking the wrong route! So he tried a new route to the counter:

He realized the problem: he was taking the wrong route! So he tried a new route to the counter: Unfortunately for him, it didn’t work. He had misidentified the issue. The problem wasn’t that he had taken the wrong route to the food. The problem was that I didn’t want him to eat the food and I had more power than he did.

Unfortunately for him, it didn’t work. He had misidentified the issue. The problem wasn’t that he had taken the wrong route to the food. The problem was that I didn’t want him to eat the food and I had more power than he did.