In West Campus, as in all of Austin outside downtown, there are rules that require new homes and shops to build new parking spaces. Minimum parking rules don’t make a lot of sense for the city in general but make even less sense in West Campus. Here’s 8 reasons those rules should be repealed:

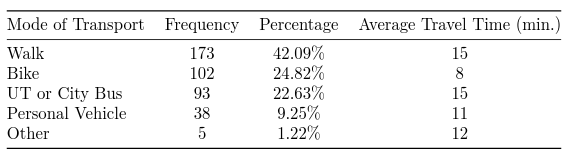

1. Most west campus residents walk, bike, or bus to campus

Austin is car-centric. But in the last 10 years since we have allowed dense, mixed-use buildings in West Campus, it has become the shining exception. Only 9% of grad students living in West Campus use their cars as their primary means of commuting!

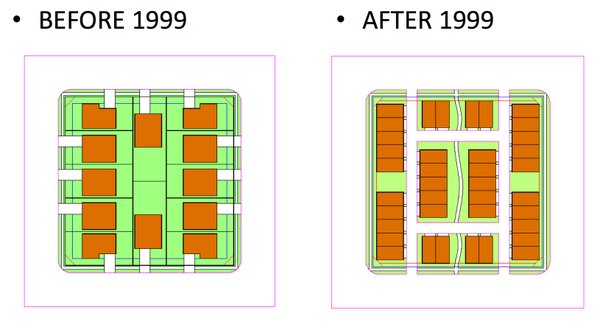

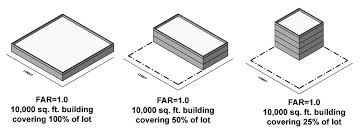

2. land used for cars is land that can’t be used for homes

Obvious but needs to be said! Tons of students wish they could live in West Campus and walk to school. Many of them end up living much further from campus. If we took the land that’s currently being dedicated to long-term parking and freed it up for more apartments, more students could live in West Campus and walk to school.

3. Building Parking increases the costs of building new homes

Building parking is expensive! An on-site, off-street parking space can cost up to $40K to build. If we let new apartments be built without parking, it’s doubtful we would see rents come down immediately. But in the long-term, reducing costs is the only way to keep rents down.

4. students choose whether to bring cars

In much of Austin, living with a car is a necessity for living a functional life. In West Campus, though, living without a car is a viable choice for most students. Students take into account the availability, cost, and convenience of parking when deciding whether to bring a car to school. When we force apartments to overbuild parking, we aren’t responding to the reality of students taking cars to school so much as creating that reality!

5. there’s already a lot of parking in West Campus

Will there still be students who need or want cars in West Campus? For sure! Fortunately for them, even in the very unlikely event that all new buildings featured no new parking, most existing buildings do have parking lots or garages. Students who value on-site parking can choose to live in a building that has it.

6. On-street spaces are metered.

Sometimes, people fear that if new apartments don’t build parking, residents will still bring cars but park them on the street. In West Campus, though, streets have parking meters, so students would be better off either buying off-street parking or not bringing a car.

7. Parking garages are ugly

This one is subjective, but overwhelmingly true. West Campus since UNO has seen a bloom of street trees, sidewalks, and interesting new buildings. The ugliest of those buildings? Overwhelmingly the parking garages.

8. It sends a message

Do we live in a society that understands the bigger picture in which auto-centric design is driving our planet into catastrophic climate change? Do we care?

College isn’t just a place to learn facts; it’s a place where we teach the next generation the values that we hold as a society. Right now, our code is teaching a “can’t-do” attitude about building better places and fighting for our environment. We can and must do better.

A parking benefit district meters on-street parking with proceeds plowed back into neighborhood improvements.

A parking benefit district meters on-street parking with proceeds plowed back into neighborhood improvements.