The major theme of the 2014 Austin elections was affordability and a major theme of City Council since then has been defining the word. Long-time readers of this blog are no stranger to tussles over the definition. Michael King took on the subject in the Austin Chronicle, taking aim at the Statesman’s editorial board and their false equation of affordability with “low property taxes”. I agree with King’s take here; the “taxpayer advocate” advice to cut, cut, cut has all the wisdom of a business leader saving money by eliminating the sales or R&D departments. Public spending can obviously sometimes offer public benefit.

But the part of the back-and-forth between the Statesman and the Chronicle I find most interesting is the question of growth. The Statesman states plainly that Austin’s growth “is not paying for itself,” while King offers the case that “growth does pay.” I’m a little irked by the question: we build homes for new people because they need homes, not merely because we can benefit as a city. But I think we can shed more light by changing the question a bit to: “What growth pays for itself?”

All growth isn’t equal

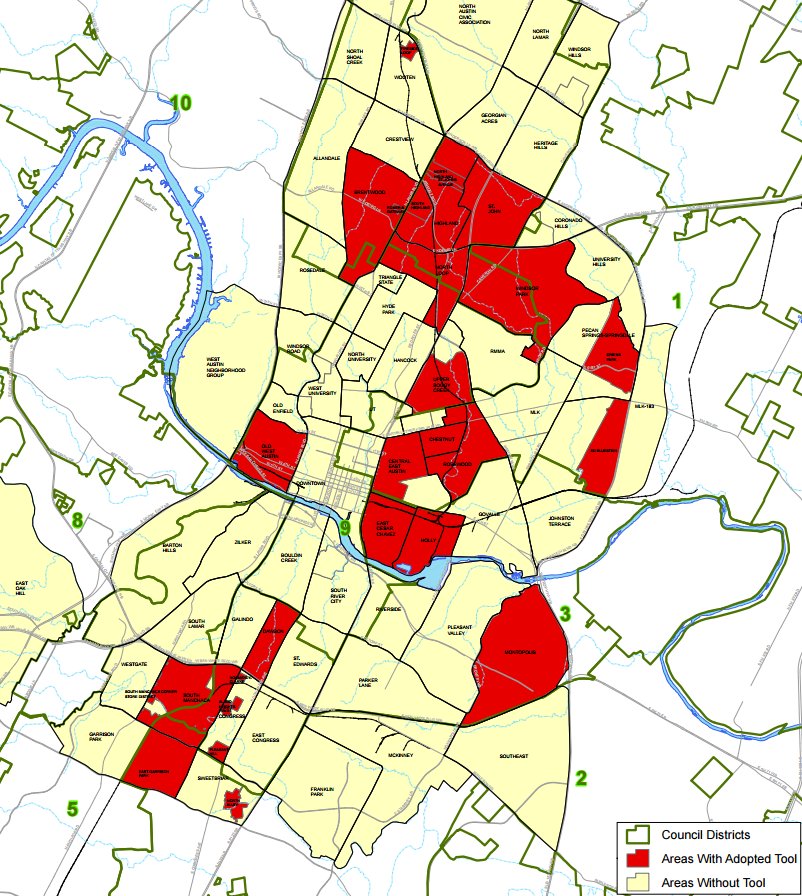

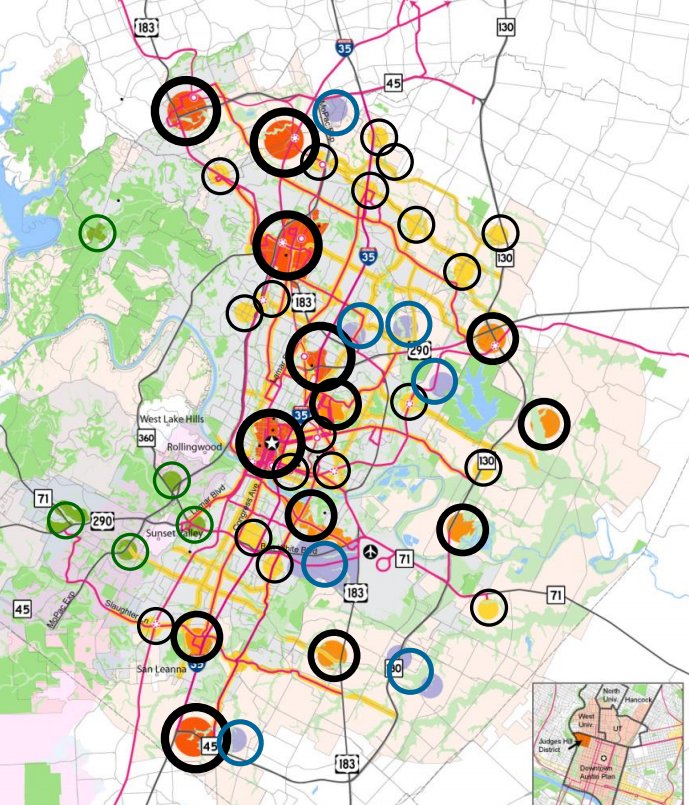

CMs Garza and Zimmerman had a debate I blogged about which kind of development imposes more burdens on the city: downtown towers or suburban sprawl?

In order to answer the question, I’m going to break the costs down into three types: building hard infrastructure (streets, sidewalks, water pipes), staffing soft infrastructure (police, firefighters, parks staff), and costs (externalities) we impose on one another through proximity.

The details of these questions can get pretty complicated, but I think the broad sweep actually isn’t tremendously complicated. For the most part, infill development–putting new buildings in places where there are already a lot of them–imposes lower costs and brings higher benefits to existing residents, while greenfield sprawl–expanding the city outward by putting new buildings in places where there haven’t been many before–imposes higher costs and brings fewer benefits to existing residents.

Infrastructure

To the extent that new buildings can make use of existing infrastructure without having to add anything new, this obviously costs the city less in the short and long term. If an old commercial building on Burnet gets replaced with a vertical mixed-use building that holds both a commercial shop and some apartments, the new combined building will benefit more people and pay more in taxes. If that can happen all while the new residents are using existing water and sewer lines, buses, electricity substations, etc., this is essentially free tax money to the city. If some of the new infrastructure needs to be replaced but some of it can be used intact, then we have a partial discount.

But even if all of the infrastructure needs an upgrade, it is still cheaper to provide it in the urban core. Replacing 10 miles of aging water pipes in order to handle new capacity (as happened in West Campus to accommodate the UNO boom) means that you have 10 new miles of water pipes to maintain. Adding 10 new miles of aging pipes to handle new greenfield sprawl means that you have 10 new miles and 10 old miles of water pipes to maintain.

The same is true for many of the city’s resources. Placing new families near existing parks means more kids get to play in the park. Placing new families far from existing parks means that for those kids to have the same opportunities, we will need to build and maintain more parks.

Soft infrastructure

Soft infrastructure is less clear. Until recently, the Austin Police Department based its recommendations on a constant ratio of 2 officers per every 1,000 people in population. This would result in the same costs no matter where growth occurs. If we are to gain (or lose) from growth, we may have to research new policies that change as the profile of our city changes.

Externality Costs

There are certainly costs associated with dense living: more people using the same roads can slow us down; more conflicts over uses of the same park means you may have to reserve the volleyball court in advance. In part, this is the flipside of better resource utilization: a park that only serves a few people will always be available when those people need it, but its costs are spread out over fewer people. The price of having the roads or parks to yourself is paying for more roads and parks.

But there are mitigating factors here. When buildings are close together, people don’t need to drive as far to get to their destinations, reducing the amount of traffic per person. On top of that, destinations that are closer together allow for more travel modes to become practical: walking, bicycling, taking the bus. This can set up a positive spiral: the more people who take the bus, the more frequent the bus can come, making the bus more practical for more people.

Conclusions

Even the analysis above is only cursory: except for those lucky enough to own the last house they’re ever going to buy, the major affordability issues we face are private, not public: mortgage payments or rent, not taxes. A measure to require all new buildings downtown have a pink granite facade to contextually match the Capitol would have enormous private costs but little direct effect on city expenditures.

But focusing in on the public costs, as the Statesman and Chronicle are doing here, we still need better questions than “should we grow?” We will grow as a city if our children want to live here, if friends from Dallas, Victoria, or Round Rock stick around after graduating UT or ACC, and if more folks like me who grew up in the Northeast decide they’re done with winter.

Similarly, the questions we have to ask ourselves about affordability are not simplistic ones about whether taxes go up or down. We can cut taxes and postpone spending for a short period–or redirect taxes in the short term from homeowners to renters and business owners, as this Council has opted for. But ultimately, if we build roads we need to maintain them. If we want a city that doesn’t have potholes, we need to pay for it.

To truly tackle affordability, we need to get beyond the short-term fiscal questions and move into the long-term structural questions about how the shape of the city affects the costs of building and maintaining it. The question is not: “Should we grow?” The question becomes: “How should we grow?” Should we grow together or should we grow apart?

The city notifies neighbors and registered civic organizations about upcoming permits. Developers seek out people they think might be affected. But it’s hard to know who is going to care and notifications are often thrown out. Don’t feel left out! If you’re at the hearing, you’re being heard. Just say what’s on your mind.

The city notifies neighbors and registered civic organizations about upcoming permits. Developers seek out people they think might be affected. But it’s hard to know who is going to care and notifications are often thrown out. Don’t feel left out! If you’re at the hearing, you’re being heard. Just say what’s on your mind.

Land development is a business. Like all businesses, sometimes you make money and sometimes you lose money. You just try to make sure that you make enough money on the winners to cancel out the losers. Focusing in on the fact that the developer is hoping to make money makes your testimony sound more like you oppose out of spite than a particular reason.

Land development is a business. Like all businesses, sometimes you make money and sometimes you lose money. You just try to make sure that you make enough money on the winners to cancel out the losers. Focusing in on the fact that the developer is hoping to make money makes your testimony sound more like you oppose out of spite than a particular reason. If council members haven’t learned economics by now, they’re not going to learn it from your three minute testimony.

If council members haven’t learned economics by now, they’re not going to learn it from your three minute testimony.

That entitles you to one vote, just like everybody else. Now tell us what you came up here to say.

That entitles you to one vote, just like everybody else. Now tell us what you came up here to say. Respecting people for volunteering time making plans doesn’t mean those plans should never change. Now tell us your reasons for or against this particular change.

Respecting people for volunteering time making plans doesn’t mean those plans should never change. Now tell us your reasons for or against this particular change.

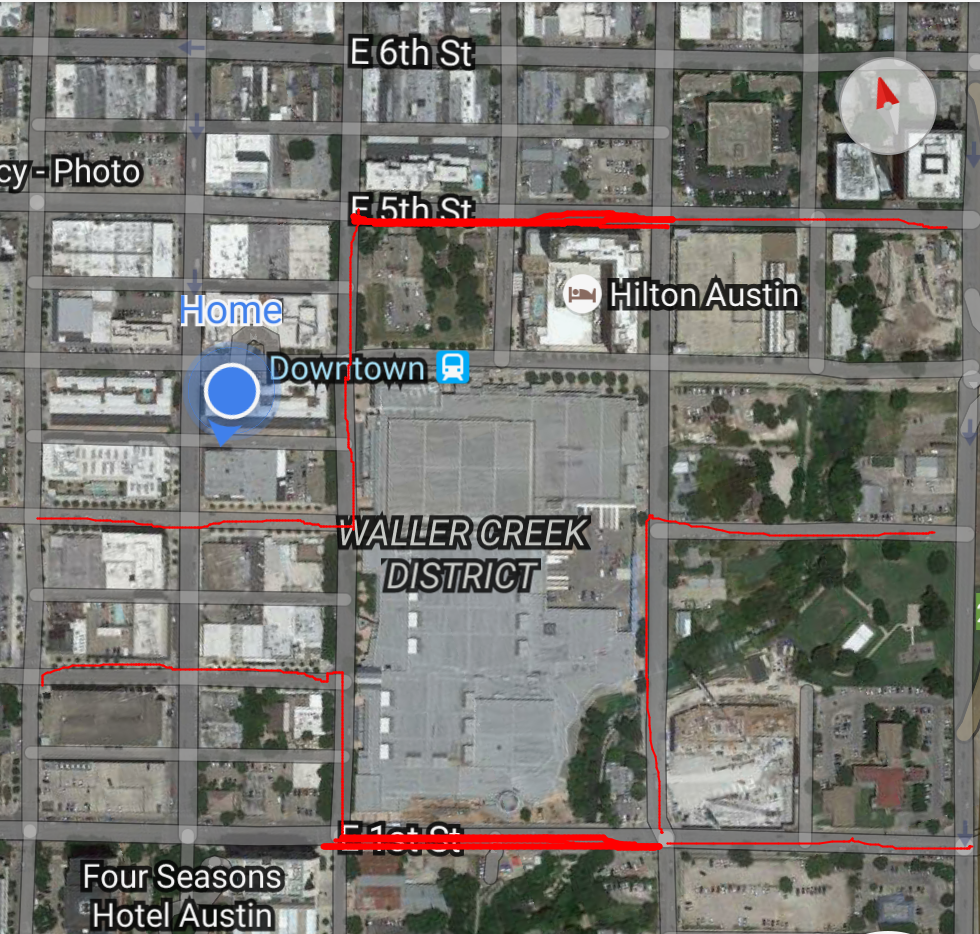

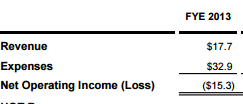

Even though the convention center doesn’t pay rent like a normal business, it loses stacks and stacks of money: $15.3m in 2013. It takes skills to run a business well enough to pay downtown rents. It takes special skills to run a rent-free business downtown and lose twice as much money as you make!

Even though the convention center doesn’t pay rent like a normal business, it loses stacks and stacks of money: $15.3m in 2013. It takes skills to run a business well enough to pay downtown rents. It takes special skills to run a rent-free business downtown and lose twice as much money as you make!

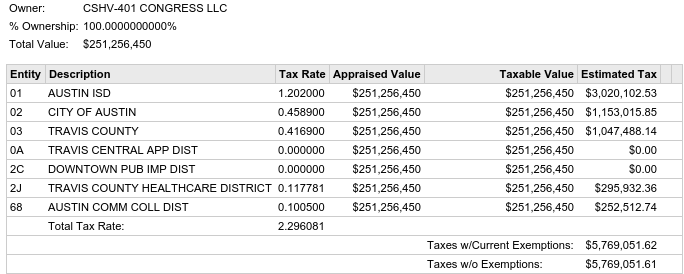

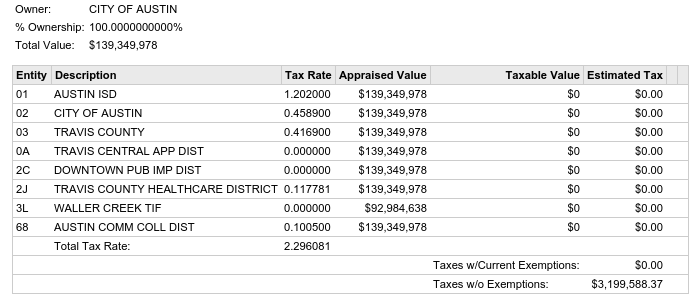

If the Convention Center takes even more blocks off of the tax rolls, that could pull millions more dollars in potential taxes away from the city, the county, and Austin schools. That’s a property tax break EVERY SINGLE YEAR that we will be using to subsidize the convention industry.

If the Convention Center takes even more blocks off of the tax rolls, that could pull millions more dollars in potential taxes away from the city, the county, and Austin schools. That’s a property tax break EVERY SINGLE YEAR that we will be using to subsidize the convention industry.