Originally posted on facebook:

Dear Capital Metro,

I am writing to you because I have grown increasingly frustrated with your communications. I read the Capital Metro blog, I have “liked” Capital Metro on Facebook, I have participated actively in the Capital Metro icanmakeitbetter ideas website, and I have attended at least one webinar. Capital Metro has made an enormous effort to engage with the public and I have responded. However, the more I have responded, the worse I think of Capital Metro. I know this is not what you intended or hoped for, but it is sadly true. Here are my areas of concern:

- Capital Metro talks disproportionately about one relatively small and marginal area of its operations.

- Capital Metro’s writings have a distinct air of spin that makes me distrust them.

- Capital Metro offers methods to ostensibly participate in decision-making, but no actual participation.

- Capital Metro offers little information to help people make informed opinions.

Disproportionate Attention

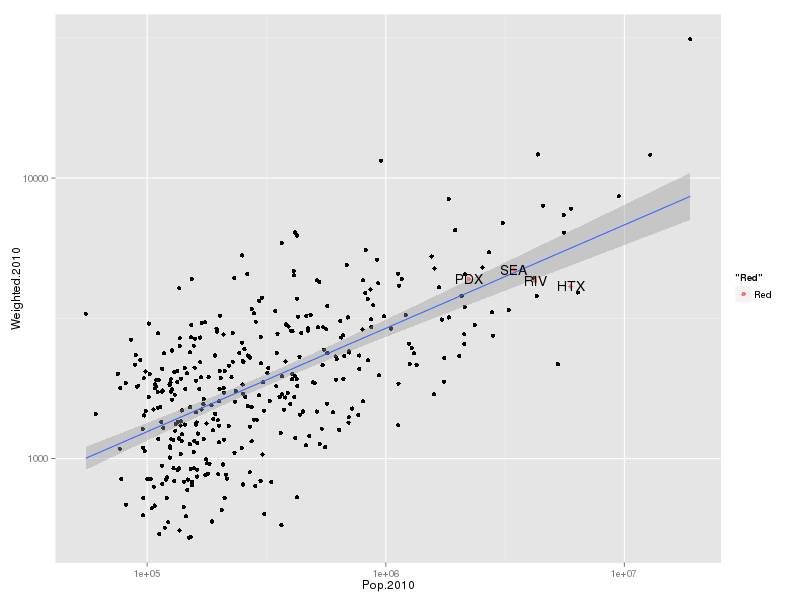

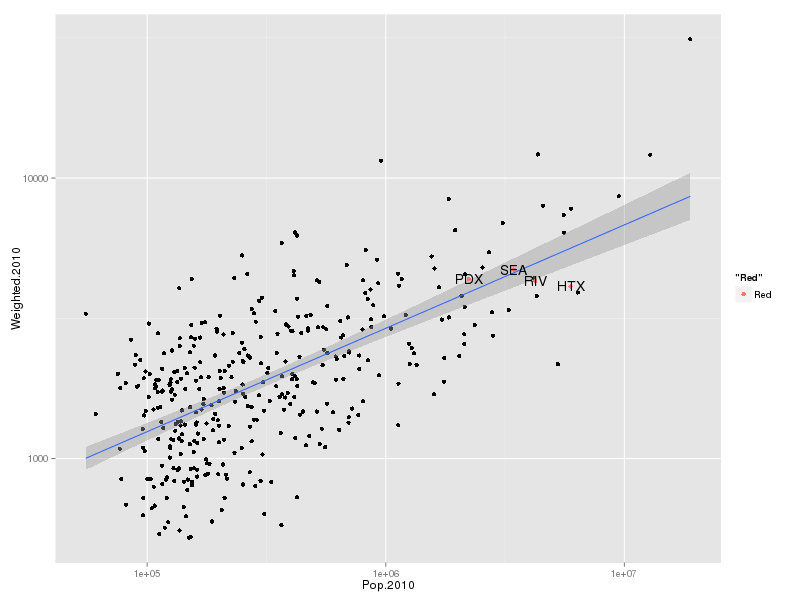

Capital Metro has made an enormous organizational commitment to MetroRail. It is understandable that this has been highlighted extensively, given that MetroRail is not only a new line, but an entirely new type of line. Yet, in the grand scheme of what Capital Metro has to offer, the Red Line remains a small, marginal line. By my understanding, MetroRail accounts for approximately 7% of Capital Metro’s budget, 2% of Capital Metro’s ridership, and an enormous percentage of official Capital Metro communication (hiring and budget announcements excluded). Daily boardings are, by my count, about 1/9 of the flagship 1M/1L bus route. Even if it achieves the full capacity allowed by physical limits, it will never carry as many people as the 1M/1L currently does. It will always remain a relatively small piece of the public transportation puzzle. I know that Cap Metro is proud of MetroRail, but the more I read Capital Metro focusing on it, the more I worry that it is distracting you from the much, much larger MetroBus system.

These fears are especially acute for me as MetroRail serves a very different, less transit-oriented type of customer than I am. MetroRail runs a relatively low-frequency line through relatively low-density parts of the Capital Metro service area. This is not the type of transportation that allows many people to live a transit-oriented life. I do not own a car, and I have deliberately chosen to live and work in areas much better served by Capital Metro (south of West Campus and just west of downtown), where it’s quite possible to get around without a car. And yet, when Capital Metro discusses transit-oriented development—ostensibly development aimed at people like me—it is in the context of MetroRail, a commuter-oriented transportation line! The impression I get from Capital Metro communications is that Capital Metro is far more interested in service to the suburbs than service to the core.

Spin

I am not the first to make this type of distinction between the commuter-oriented MetroRail and the core bus lines. While many people are very enthusiastic about the arrival of rail to Austin, many of the most informed and transit-oriented people in the city have not been. When I attended the annual meeting of the Bus Riders’ Union, the only organized grouping of Capital Metro customers I know of, the Red Line was universally blasted as a waste of money. There’s a community of transportation and urban issues bloggers and blog-commenters in Austin that have made detailed, data-oriented critiques of the Red Line. Reading Capital Metro communications, though, makes it sound as if Capital Metro is completely unaware that MetroRail has ever been criticsed. Certainly, no substantive plans to ameliorate the highlighted problems have been offered.

Instead, modest achievements—and even sometimes failures—are trumpeted as major successes. In one post I found myself resenting quite a bit, the Capital Metro blog breathlessly announced that MetroRail transported 2,800 passengers in a day. [http://capmetroblog.com/2011/11/29/metrorail-motivation/] To people unfamiliar with transportation, this may sound like a large number, but it is approximately 8% of the daily ridership of Houston’s MetroRAIL or 20% of the ridership of the #1 bus. (Correct me if I’m wrong; there are not similar breathless posts about #1 bus ridership.) However, even at that relatively tiny number of riders, MetroRail failed to scale, being forced to scramble buses for stranded passengers. And the buses beat the train to the destination! To somebody who is used to riding the normally efficient and effective bus, the facts read as a catalog of failures, not as the amazing achievement the blog tone implies. I want to know what Capital Metro is going to do to fix the problem of an expensive train line failing to scale to even 20% of the ridership of a bus line and failing to outperform buses scrambled to the scene.

I know that the point of providing the Capital Metro blog is to perform public relations on behalf of Capital Metro. But there is no reason it needs to be so relentlessly cheery. You can have an honest discussion about real problems with service and what you are attempting to do to improve on them. In the tech industry, for example, providers of essential services often write long posts honestly discussing their own failures. (See, for example, http://aws.amazon.com/message/65648/) I believe that adopting a similar, honest tone to your blog, not just discussing what you see as Capital Metro’s greatest successes, but also discussing what areas are poorest served, what parts of your service are breaking the budget, etc., would be well-received. Instead, I get the feeling from the tone of the posts in the Capital Metro blog that no matter what happens, it will be spun as a success. So why should I trust anything Capital Metro has to say?

Participation

I have participated in Capital Metro’s ideas website. I have added three ideas of my own and participated in many other discussions. No Capital Metro employee has responded to any of my ideas, except to mark it as “acknowledged,” whatever that means. Very, very few ideas have been marked as accepted on the whole site, and of those that have been, most have merely been ideas Capital Metro had already implemented or planned on implementing independently. Even fewer ideas have been explicitly rejected. Instead, they languish uncommented on and to all appearances unread.

The core of a participation system is a pipeline whereby ideas can reach engineers and decision-makers who can give feedback on them. This can be done on any number of platforms, from email to Facebook to websites to suggestion cards to face-to-face meetings. The platform itself is only a tool for facilitating the user-to-decision-maker communication. What it feels like Cap Metro has done instead is to work very hard on the platform but not at all on the core communication. This is worse than nothing. I do not want you to request my input if it will go unread or uncommented on. It’s a waste of my time. What I suggest you do is either dedicate resources to responding to these ideas or shut down the platform for soliciting them. Maybe you can only respond to the top 5 ideas per month; that’s fine. But don’t solicit feedback and then ignore it. It’s insulting.

Information

Similarly, whenever Capital Metro makes changes to its service, it provides a data-less batch of justifications for these choices, and then solicits input. The #5 route was cut back on weekends and the #1 expanded, and we were offered the explanation that this was driven by ridership levels. Was this a good choice? If I use the #5, probably not; if I use the #1, probably. That is as good as feedback can possibly be with the information provided. When you solicit feedback without providing information, the best thing you could possibly do is ignore it, because why would you want to listen to uninformed opinions? Either provide enough numbers to justify your decision quantitatively or cease looking for input on these decisions.

In general, I find that the most quantitative, numbers-oriented analyses of Capital Metro service comes not from Capital Metro, but from bloggers, such as Chris Bradford and Mike Dahmus. There’s no reason this should be! You have the numbers while the bloggers are often merely doing their best to recreate or estimate. You can make public the reasoning that went into these decisions in perfect detail. If this isn’t something you want to do, then you should stop presenting the service changes as open for discussion. Without the numbers that went into your decision, the discussion is a waste of everybody’s time.

Conclusion

I love Capital Metro. My whole way of life depends on it. It gives me freedom similar to how many 16-year-olds feel about their cars. This is why I want to participate in the ongoing discussion about Capital Metro services. And that is why I have been so excited that Capital Metro has made such a commitment to participate in social media and so many communications platforms. But somewhere along the way, your strategy has gone wrong. You have invited participation on a million platforms, but actually participating leaves me feeling unheard and hollow. You offer many cheery blog posts, but little solid information. I feel far more estranged from your organization than I was to start with. That is the bad news. The good news is that means you have a lot of room to improve. I sincerely hope you do, and am more than willing to work with you if you wish to work with me.

Yours,

Dan Keshet