I’ve previously discussed the difference between two kinds of affordable housing: the mandatory kind (means-tested, reduced rent programs) and the market kind (housing that is inexpensive on the open market). In the Burnet / Rockwood case (history: 1, 2), however, there were really three concepts of affordable housing under discussion: lowering market rents, providing selective rent reductions, and providing deeply affordable housing for the very poor.

Zoning

Councilmembers’ approach to zoning, in their own words, part 2

Last month, City Council took up one of their first large zoning cases, a proposed apartment complex near Burnet Road. Many of them used the opportunity to expound not only on the case in question, but some of the principles behind their decision, and I duly blogged those takes. Zoning changes require 3 “readings” (i.e. 3 different votes). If there’s no disagreement, all 3 readings can happen on the same night. But in this case, there was disagreement, so they only passed the vote “on first reading,” and this last Thursday, revisited it. If you’re interested in the background and outcome of the decision, check out Liz Pagano’s take in the Austin Monitor. Me, though? I’m interested in hearing what the Council Members had to say about their approach to zoning.

District 10 Council Member Sheri Gallo

Gallo here notes that the majority of Austin rents, neighborhood associations don’t always do a good job representing them, and it’s the responsibility of City Council to look out for all residents, not just the organized ones. Readers of this blog will be familiar with both the renting and neighborhood association ideas.

Here, Gallo gives her opinion that the reason why rents have risen in Austin is an imbalance of supply and demand, and suggests more housing supply is needed to stop price increases. This, again, is familiar territory on this blog.

District 3 Council Member Pio Rentería

CM Rentería, similar to CM Gallo, believes that raising supply will stabilize prices.

District 4 Council Member Greg Casar

Casar offers a number of ideas here. First, he discusses a “filtering up” mechanism, where, if new housing doesn’t get built, old (or “vintage”) housing can become more expensive, giving as an example housing his brother lives in in Los Angeles.

Another two ideas that Casar argues for are that: 1) building housing is in and of itself, a “community benefit.” 2) There is an additional “economic integration” community benefit to having some portion of that housing be mandated Affordable Housing. Neither of these ideas are new to council. Nevertheless, it’s interesting to hear both of them in the same speech. Frequently, the “economic integration” argument appears on the side of somebody arguing against denser zoning. In this case, though, Casar appeared to be arguing for greater density as a mechanism for making more Affordable Housing economically viable for the developer.

Mayor Steve Adler

I publish this not because Adler offered much background on his approach to zoning here, but because of the previous rarity of seeing a Council Member ask a developer to consider greater density on a site. (Sorry, I accidentally cut the video short; the developer said yes, he would consider it.)

District 2 Council Member Delia Garza

Garza offers two items of note: 1) delays in the development process add to the costs of housing, and 2) Austin is a high-demand city, and when there isn’t enough housing supply in richer areas, this adds to gentrification pressures in poorer areas.

District 8 Council Member Ellen Troxclair

Troxclair offers a bit of a procedural take, arguing that Council’s way of using zoning as a negotiation tool encourages parties to take extremist positions. She appears to have misspoke when she said she couldn’t support MF6; she voted, as she did in the previous reading, for the higher-density MF6 and against the lower-density zoning.

The Developer

Finally, we hear from the applicant, C.J. Sackman, the developer of the project. I’m including this testimony not because his views will have lasting impact on the Council the way that Council Members’ do, but because they’re broadly representative of developers’ views.

The Rest

CM Pool (District 7), CM Kitchen (District 5), and CM Houston (District 1) emphasized that, because there was disagreement between a neighborhood association objecting to the project and the developer and because the two hadn’t fully negotiated, they wanted to pass a lower zoning category on 2nd reading only, to pressure the two sides to negotiate. CM Zimmerman (District 6) thought there had been enough testimony, and moved for the decision to be made for the higher zoning category on 3rd reading. Mayor Pro Tem Tovo (District 9) voted with Pool, Kitchen, and Houston. In her testimony, Tovo focused on whether the developer could have provided steeper discounts on the Affordable Housing apartments, to target a poorer population.

What Compact and Connected Means to Me

On March 23, I presented at the CNU Central Texas City Matters 20×20 panel on the subject of “Compact and Connected” and what that means to me. The format of the presentation called for a ton of pictures. This post is adapted from my presentation. Thanks to the great team at CNU for prompting me and pushing me to put this together.

To me, Compact and Connected means independence and an opportunity for personal growth. I’m rare in Austin as somebody who is eligible for a driver’s license but doesn’t have one. This is the story of how that came to be, and how much the places we live affect who we are.

I grew up in Newton, MA, a gorgeous but expensive Western suburb of Boston. My house, an 1890 Victorian, would fly through the historic landmark commission in Austin, but was typical of the city block I lived on. The place had many of the amenities that school-aged parents wanted: good schools, large lots with green lawns (9600sf), an acclaimed public library, and easy freeway access to downtown Boston.

Although all of our parents had moved there for the schools, to myself and my 15-year old friends, we as children were frequently bored. The first thing we wanted to do when we were old enough was get a driver’s license. To us, a driver’s license meant freedom. Freedom to see our friends on our own schedule, to go to restaurants, to go to parks, to go into Harvard Square and listen to street musicians. Freedom to explore our world.

For me, though, it was not meant to be. About the time I’d be going for my learner’s permit, I became ill. That meant two dramatic things that made a profound impact on my life for decades to come: 1) I was unable to learn to drive, and 2) I missed too much school to graduate in four years, and took a fifth year doing an alternative learn-from-home program.

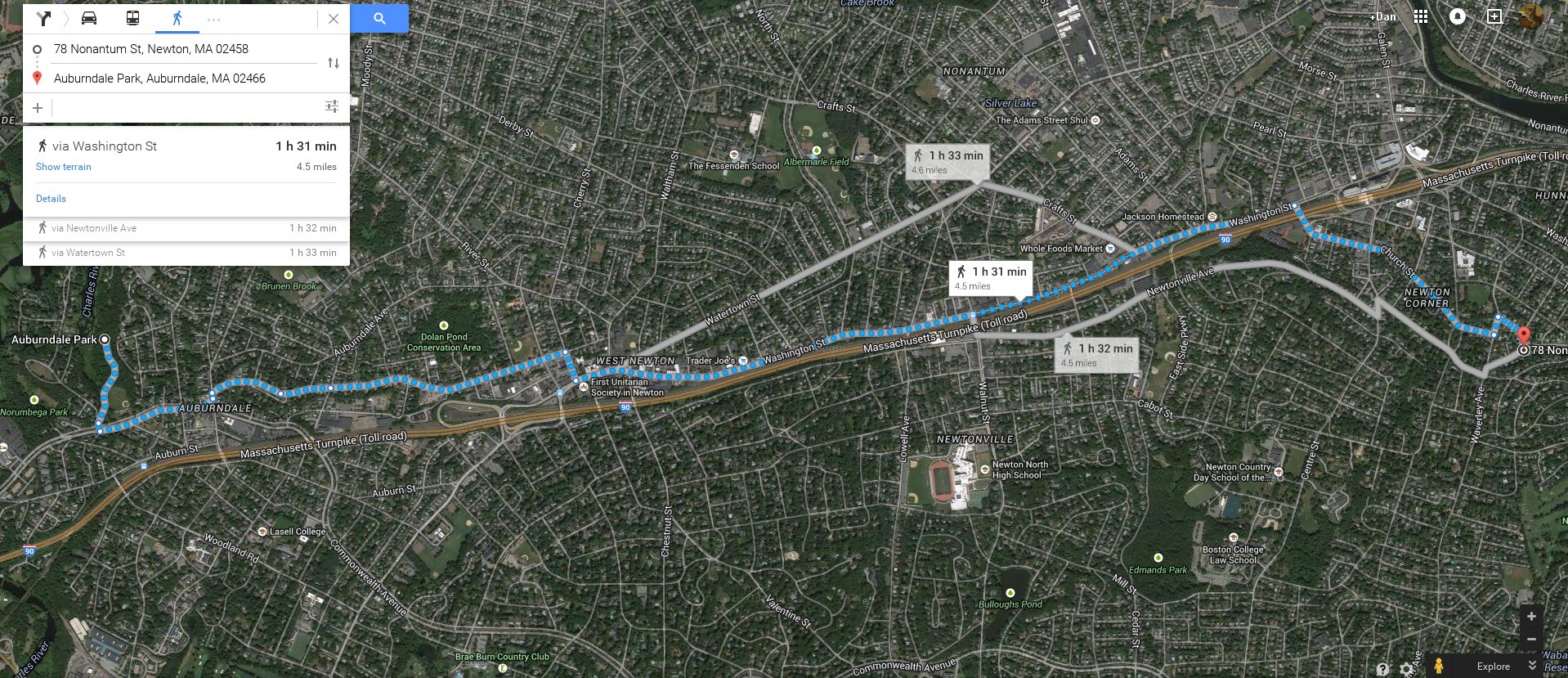

During that fifth year, I felt the sense of deep isolation that car-oriented cities create. Newton was built centuries before the automobile, but the last trolley lines had been torn out decades before I was born and the city had been remade over the decades to accommodate cars. It would take me 3 hours to walk to one of my closest friends’ house and back.

The closest grocery store was 35 minutes there and a lot longer than that walking back carrying groceries.

That acclaimed public library was 45 minute walk. The only commercial cluster near me didn’t offer much (pizza and a convenience store is all I remember) and closed early. Despite living in what truly was one of the most desired places in Boston, I literally couldn’t feed myself, couldn’t see old friends or make new ones, find any sort of job, or continue my education without being 100% dependent on my parents and their cars.

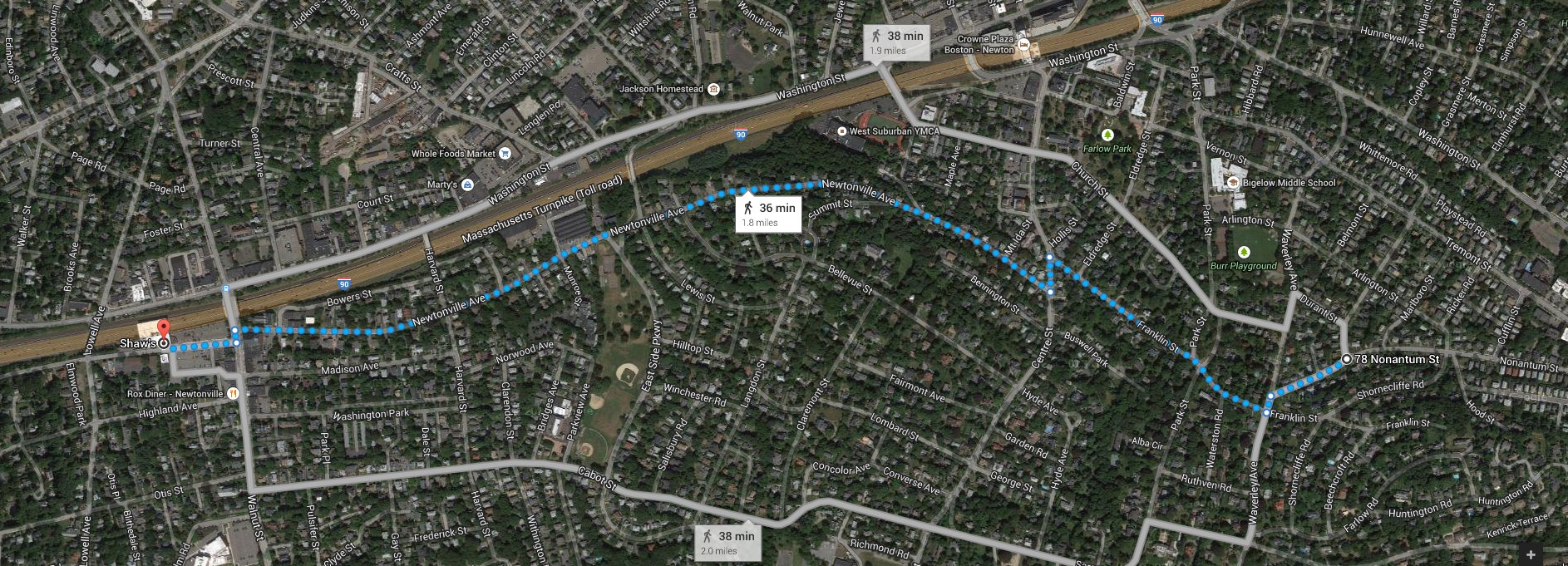

So, about two weeks after I graduated high school, I moved into the compact, connected community of North Cambridge. What do I mean by compact and connected? Compact: Instead of living in my parents’ 3,100sf home, I lived in a 500 sf studio apartment in a modest 24-unit corner complex.

What do I mean by compact? The houses along my new street were closer together, and multiple families shared a single house.

And just as the distance between people’s homes was more compact, so too were the distances between my home and the places I needed to be. There was a grocery store 10 minutes walk from me.

There was a smaller grocery store with high-quality produce literally across the street.

While the public library was a bit more “compact” than Newton’s, it was literally 500 feet from my home, and I would stop by sometimes multiple times in a day.

So, for me, compact meant the independence to be able to feed myself, take care of myself, and get an education. So, you might be asking, how does this apply to everybody else? Not everybody finds themselves in a situation where they can’t drive. For them, does it matter whether you can get somewhere in 10 minutes on foot vs. 10 minutes in a car? If you drive, you already have the independence to take care of basic needs, even car-oriented places like Newton.

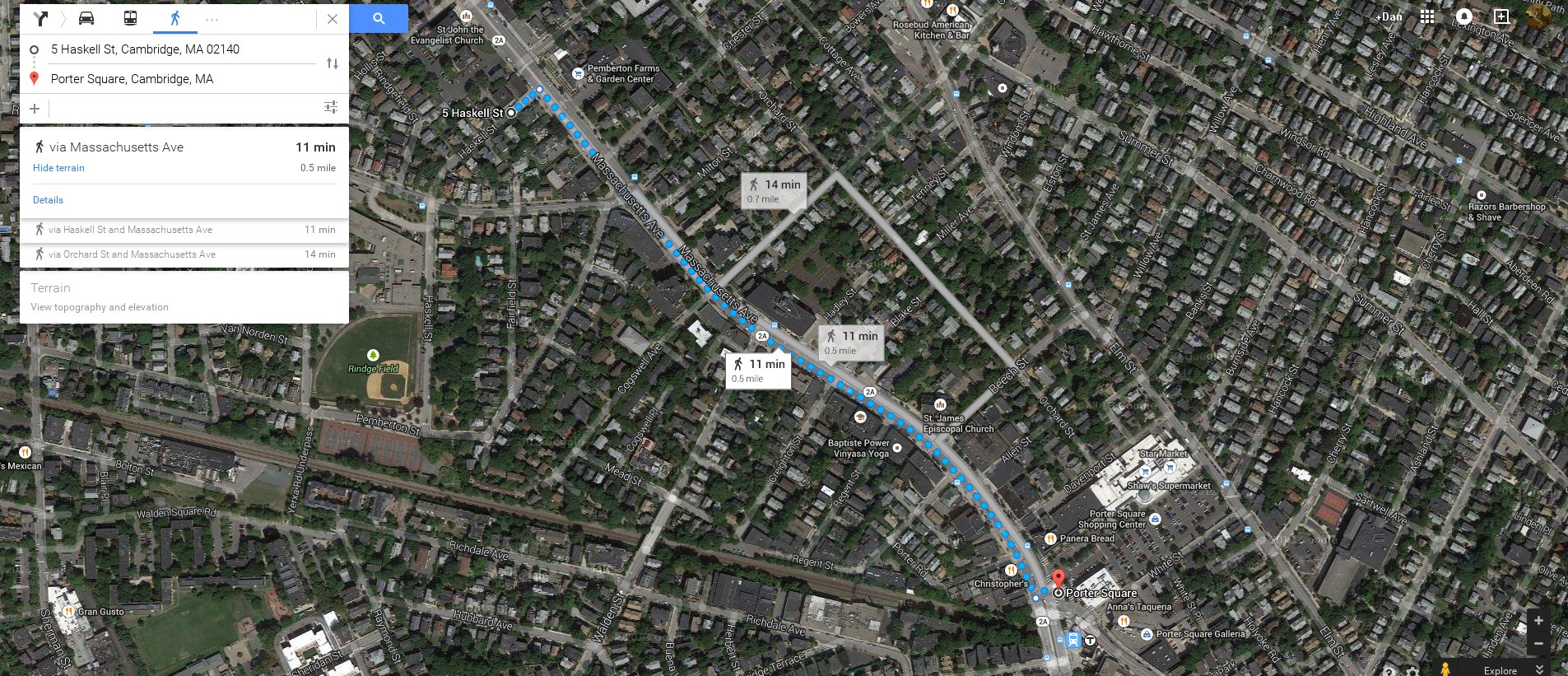

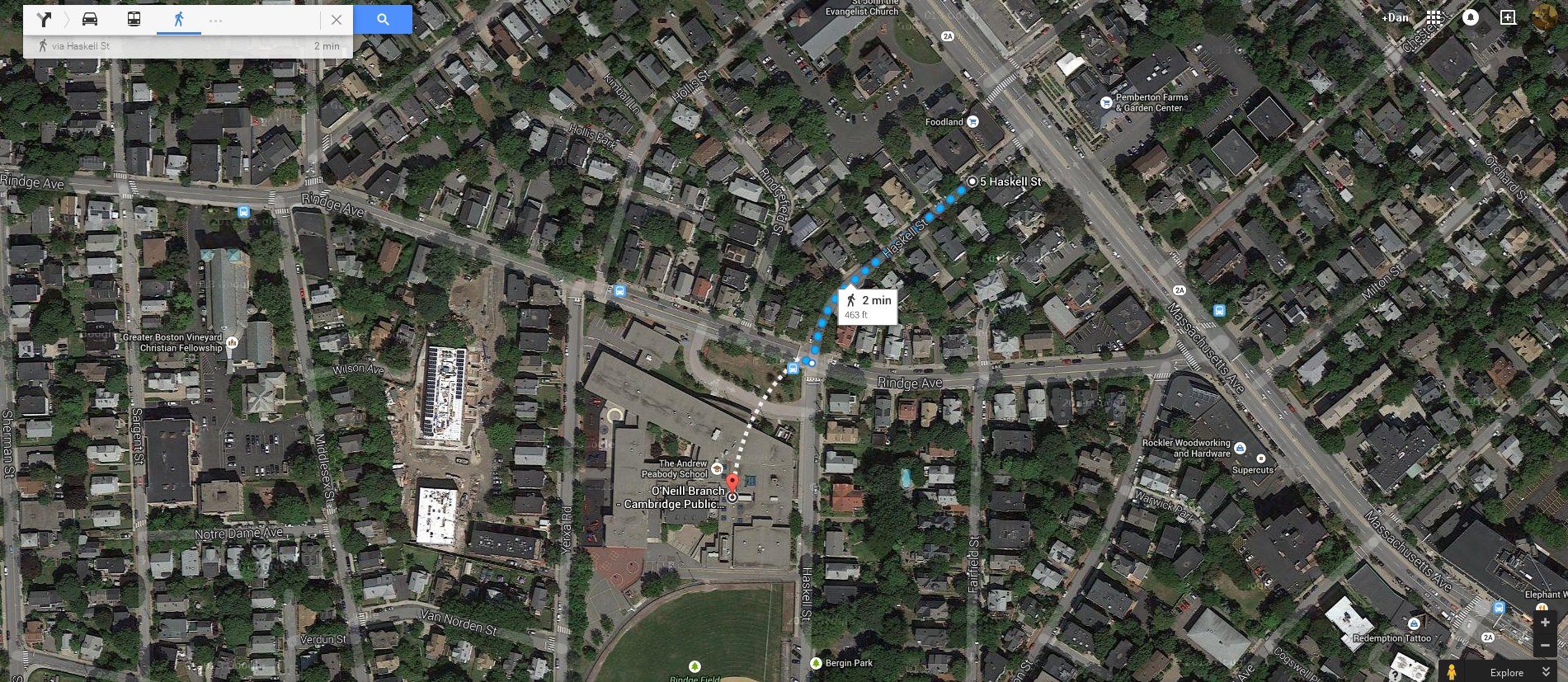

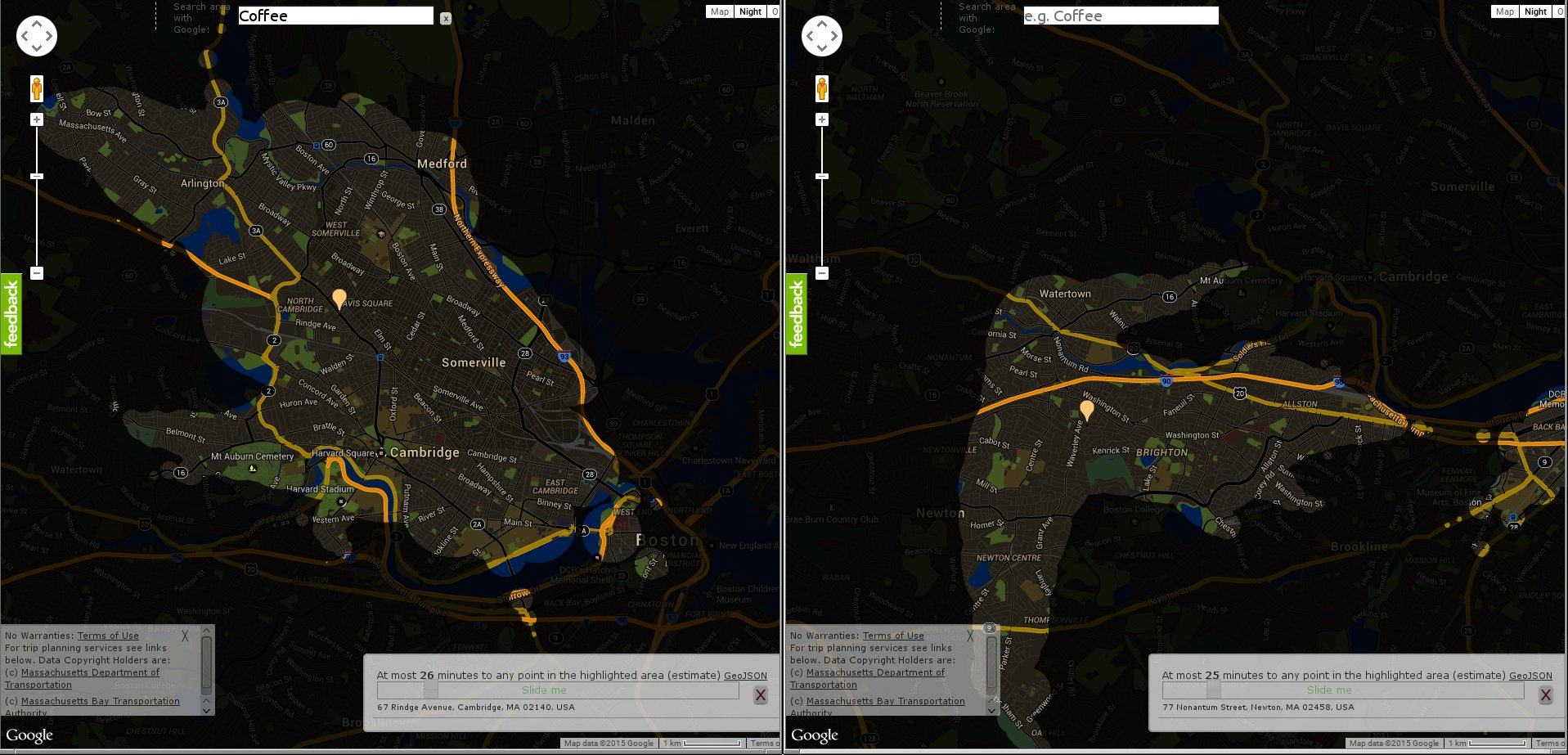

That’s where connected comes in! Newton and North Cambridge were both on public transportation routes. Here is a visual of places I could quickly reach on public transportation from my homes:

Cambridge’s density allowed for more frequent, better public transportation, that had a geographically broader reach than that in Newton. But that’s only a tiny portion of the story. Because Cambridge was built densely, with things closer together, that geographical reach translated into way more destinations. Here, for example, are the restaurants nearby each of my homes:

Note not only how many more there are in Cambridge, but the variety. By moving to Cambridge, I exposed myself to Tibetan, Bengali, and Nepalese food, to a little Japanese-oriented mall, and to specialty book stores. I got heavily involved in local political movements of all flavors, and heard dozens of languages spoken on the street. Perhaps most importantly, I was able to take night classes in Computer Science at a local college and find a starter job in the tech industry, without which I wouldn’t be employed as a computer programmer today.

I’m no longer the isolated kid I was, and I’m sure I could make a fine life for myself in the suburbs. But, for me, compact will always means independence, and connected will mean personal growth and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

A Very Positive Development

As Austin Contrarian documents, Council Members Riley and Spelman, and Mayor Pro Tem* Cole, have introduced a very positive item on the agenda for Thursday’s City Council session. The item would allow buildings to 1) waive “minimum site area” rules and 2) waive minimum parking requirements when they build apartments less than 500 square feet on either Core Transit Corridors or in Transit-Oriented Development zones.

Quick glossary (and readers, correct me if I’m wrong):

- The minimum site area is essentially a cap on the number of units an apartment complex can have per acre.

- Minimum parking requirements are rules requiring a certain number of parking spaces per apartment. The exact requirement varies based on the number of bedrooms in the apartment.

- Core Transit Corridors are essentially big streets like Lamar or Burnet. You can identify them by the presence of large apartment complexes.

- Transit-Oriented Development zones are special zoning areas near transit stations that allow developments with less parking (to take advantage of their proximity to transit) in exchange for some special design requirements.

The reason this is such a big deal is that, as Austin Contrarian says in the link above, minimum site areas and minimum parking requirements are some of the biggest impediments to providing homes in Austin. If developers weren’t required to build parking for every lot, they could create targeted developments to people who don’t own cars. Even if currently there are few people who would be willing to go without a car, the developers can still make money by reducing the price because they won’t have to pay for the extra land for parking. The reduced price for a nice, centrally located apartment might lure some people to give up their cars.

On its own, this change will not bring a construction boom or affordability to Austin. As I discussed, only allowing density on select streets greatly limits opportunities for building. The same logic that makes it useful to get rid of minimum parking requirements on the Core Transit Corridors themselves should apply to areas near the CTCs as well. After all, most people who don’t have a car can walk a block to the transit corridors as they can get a unit on the exact street itself. Even if those streets weren’t upzoned to multi-family, eliminating parking requirements would allow many more people to build Accessory Dwelling Unit–also known as granny flats, garage apartments–small “extra” units on a Single Family lot. Indeed, the same logic that says that minimum parking requirements aren’t needed near transit should apply everywhere. Few people may want to live far from transit without a car, but if somebody wants to, more power to them.

Similarly, the same logic that says that a unit less than 500 square feet could benefit from reductions in parking minimums could just as easily apply to units greater than 500 square feet. 500 square feet is plenty for many single people, but reducing parking requirements for larger units might allow more families currently priced out of the core to ditch a car (perhaps one of two cars or perhaps both if their circumstances were right) and move to a more central location.

Still, this really is a fantastic development, both because of the direct effect it would have and because of the way it focuses on some of the real issues: onerous minimum site area and parking requirements getting in the way of building transit-friendly, centrally-located housing. I urge you to write City Council and express your support for Item 40, your thanks to Riley, Spelman, and Cole for sponsoring it, and a request that Leffingwell, Morrison, Martinez, and Tovo support it as well.

One last explanatory note: the Item itself is not an ordinance. It is merely a request that staff write an ordinance and bring it to Council. This is actually the second stage in the process; the first was a resolution sponsored by Council Member Spelman asking staff to study the issue of microapartments. Even if this item passes Council on Thursday, there will still be a long way to go before it becomes law.

* For those not in the know, “Mayor Pro Tem” is essentially “vice mayor.” Both the mayor and the Mayor Pro Tem are councilmembers with equal vote weighting as any other councilmember. City Council etiquette dictates that you always refer to and address the Mayor and Mayor Pro Tem as such, though, and not merely as “Council Member.”

The Affordable Housing that Bonds Give, Policy Takes Away

In November 2013, Austin voters passed a 10 -year, $65m housing bond. I never thought this bond would do much to affect affordability; Austin is expensive because it’s like a game of musical chairs with more players than chairs. Compared to the size of the game, the bond was tiny*.

But just three months later, the Austin city council is threatening to take away any possible affordability gains by, at a stroke, eliminating one of the major options for affordability in the city: sharing a house or duplex with enough friends to bring prices down. (To read more on the issue, see this facebook event.) To stretch the musical chairs analogy a little far, it’s as if the city has decided that, even though there are thousands of people on the outside looking in, unable to find chairs, the best option right now is to reduce the number of friends allowed to share a bench. The results of this ordinance will be to scatter some of those who want to share houses to currently affordable parts of the city, raising prices there, and price others out of the city entirely. Taken together, the net effect of the bond and ordinance will be to: 1) raise taxes, 2) use that money to fund quality-of-life issues for the squeaky wheel homeowner minority in university-adjacent neighborhoods. If you, like me, feel like this is a really bad idea, I encourage you to take action, writing to City Council or speaking in front of the Council.

* The city says that the previous bond of about the same size funded 2,409 units over the course of its 8 year life or approximately 300 new units per year, in a city of 850,000 people. By contrast, the private market added 11,834 units in 2013, according to the Census Bureau. Screenshot here; data here.

Zoning: the Central Problem

Zoning is the central question for Austin, affecting virtually every issue we touch on. In previous posts, I’ve argued that the path to walkability is upzoning of central Austin neighborhoods near downtown and UT. I’ve also argued that upzoning is what’s needed to make Austin affordable. And the much-debated densities for the urban rail route are largely defined not by physical geography, but zoning geography.

Yet it’s a question I am only beginning to educate myself about. When Chris Bradford wrote his letter to City Council opposing the Highland route for urban rail, he was able to get much more specific than I have been:

In 2008, the City upzoned hundreds of tracts on Core Transit Corridors throughout the urban core for Vertical Mixed Use on the premise that these streets would be the focus of our transit investment and thus particularly suited for dense development… It is thus remarkable that Project Connect’s planners managed to choose the only sub-corridor — Highland — that lacks either a current or future Core Transit Corridor connection to downtown or UT.

Getting to know Central Austin zoning

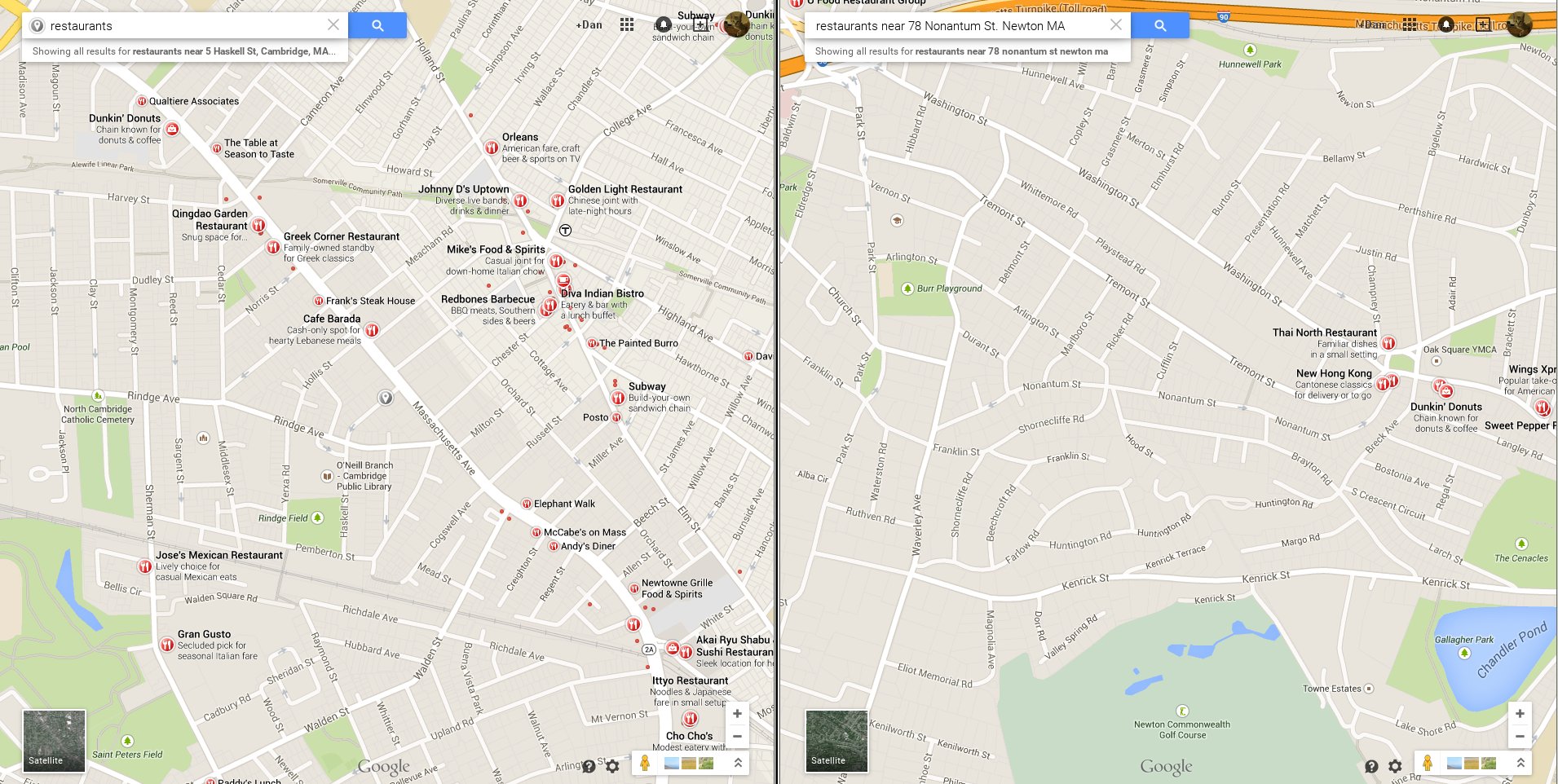

So I sought out some maps to give some visual clarity to Chris’ point and found them here. The first map shows current and future Core Transit Corridors and the lots zoned for Vertical Mixed Use (VMU) along them:

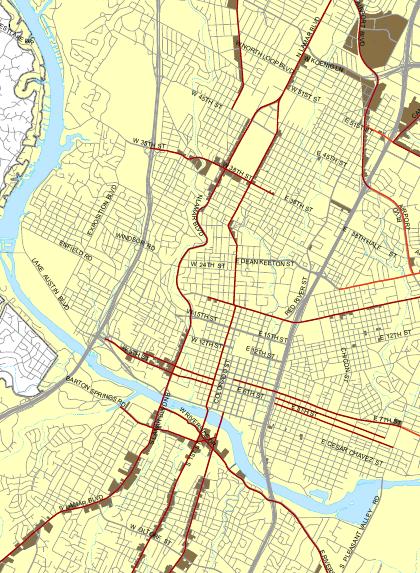

There is indeed VMU zoning along South Lamar, South Congress, North Lamar, Guadalupe, Burnet, Airport, and Riverside. But, as Chris mentions, there is a big, transit-corridor-free, mixed-use-free gap north of UT, between Guadalupe and I-35, precisely where Project Connect is planning to run a train. Based on this map, you might think that South Lamar is the best corridor for transit, followed by South Congress. These are the streets with the most VMU zoning along them. But VMU isn’t everything. For a more complete look at what the zoning for these streets looks like, we turn to the general zoning map:

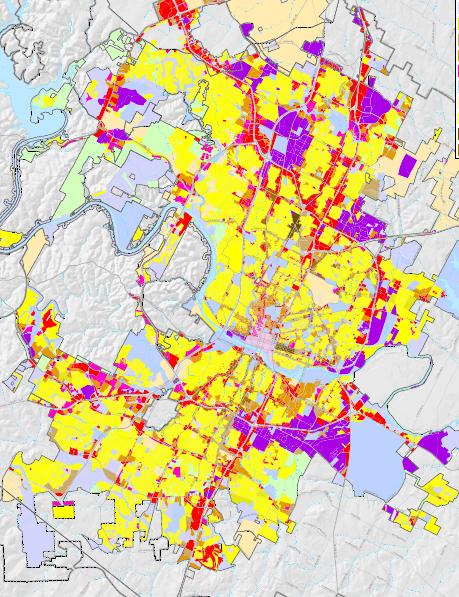

This map is all of Austin. It’s hard to see specifics, but I include it to make the general point that Austin is largely zoned single-family (SF). In much public discussion, people focus heavily on new condos or on commercial areas, but I believe this is largely because that’s the interesting part of Austin. In terms of land area, it’s tiny. Now here’s a much smaller portion of that map, showing a small, central area of Austin:

A few things jump out:

- Despite talk of central Austin becoming unrecognizably dense, a majority of central Austin by area is reserved for people to live in not-dense single-family housing.

- VMU areas around South Lamar and South Congress are largely confined to those streets themselves. Just one parcel away from major streets, you are no longer allowed to build multi-family housing, let alone tall or dense mixed-use buildings.

- There are three areas in Austin with real penetration of multi-family housing into a neighborhood and not just a major street: Downtown, East Riverside, and West Campus.

- The stretch of the proposed rail line in the Highland subcorridor from UT to Airport Blvd is zoned for low-density single family housing.

Single-Family Sea as Impediment

Zoning touches on most issues Austin faces. But with these maps in mind, I think we can get more specific: one of the major zoning problems Austin faces is the sea of low-density single-family housing surrounding Austin’s islands of high residential density. Upzoning downtown- and UT-adjacent neighborhoods to allow more than SF homes could help solve many of our problems:

- Transit Ridership We are a decent-sized city and should have no problem siting a rail line through density, where it will be used. Yet to hop from downtown to the business and political class’ preferred site of future density (Highland), it would have to go through a sea of low-density single-family housing.

- Housing Affordability There is ample land on which enough new housing could be built to satisfy the rich, the middle-class, and the poor. Even if the new housing is expensive, it would lower overall rents in a game of musical chairs. But it wouldn’t have to be expensive; building affordable housing is much easier when every home isn’t required to provide expensive amenities like personal gardens or yards, and homes (apartments or condos) can share walls and foundation.

- Tax Affordability It’s also cheaper for the city: expensive amenities like sidewalks and utilities can be provided cheaper the more people who share them.

- Transportation Affordability Housing built in central Austin is close enough to job centers that household transportation expenses could be eased by requiring fewer cars to achieve the same or better mobility. And fewer cars means less overall traffic.

Building islands of density surrounded by seas of single-family housing loses many of the benefits of the density, while retaining its costs. This is a point similar to that made by Jeff Wood in his endorsement of the Guadalupe-Lamar route, where he calls for the creation of a single large employment district that isn’t separated by low-density areas. And it really would be easy to do anywhere in Central Austin. West Campus isn’t denser for natural reasons (e.g. better soil, less hilly), but policy ones: the city passed UNO, allowing more housing to be built. Given the enormous demand for housing, any downtown-adjacent neighborhood that the city removed SF shackles from would see growth.

What I’m NOT Saying

1. I’m not saying all SF housing is terrible and should be gotten rid of. As I have said before (and again), I respect others’ preferences for living not only in single-family housing, but single-family neighborhoods (that is, neighborhoods that exclude/outlaw multi-family housing). When my last roommate and I parted ways, I moved to a small downtown condo and adopted a cat; she adopted dogs and moved a few miles away from downtown to find a place she could afford a fenced-in yard. I would no more tell her she’s wrong to want a garden and yard than I would expect her to tell me I’m wrong for wanting a cat. And, as you can see from the larger map, Austin the city (let alone the suburbs) is not remotely in danger of seeing single-family housing go extinct. To a first approximation, all of the housing areas of Austin are single-family housing areas.

2. I am not saying we should remake all of Central Austin to resemble downtown, with its soaring skyscrapers. As fast as Austin is growing, we would still run out of people to put in them before we got even close to that point. Even the relatively dense neighborhoods of West Campus and East Riverside are largely without downtown’s skyscrapers, and opening up more land area to denser building would satiate demand without every building going 20 stories high.

3. I’m not saying the city should demolish single-family homes. People who live in single-family homes close to downtown can go right on living in them; they just will now have the option of building more on their land or selling it to somebody else who wants to (or selling to somebody who doesn’t want to). The one thing they lose is the right to forbid their neighbors from building.

Politics

We are moving to 10 single-member districts and one at-large mayor (10-1) soon, a system that Chris Bradford worries will lead to “ward privilege” (Councilmembers granting each other carte blanche to veto development within their own district). Mike Dahmus describes a system similar to this already happening within one of the city’s most influential citizen groups, the Austin Neighborhood Council (ANC), where outer-Austin neighborhood associations support central Austin neighborhood association’s decisions about central Austin neighborhoods in solidarity, even if the outer Austin neighborhoods might be better served by central Austin densifying.

But I’m less convinced than ever that there are hard-and-fast rules about local politics. At least 9 out of the 11 incoming city Councilmembers will be new, due to term limits. A tiny fraction of voters vote in local elections and an even tinier fraction understand the full range of issues. A dedicated organization focused on understanding and changing local politics in an urbanist direction could make a tremendous difference. As the leadership of AURA has found, there is a hunger within many communities for this type of politics. Developers make a poor counterweight to neighborhood politics and a true grassroots coalition that wants to see dense development in central Austin could change things enormously.