With the completion of the runoffs, Austin’s next City Council is set. Although it falls short of the densificatron the Austin Chronicle mused about, it is being widely hailed as the most urbanist-friendly council in recent memory. How did we get here? Well, I’d like to believe it’s because the world is coming to understand that building awesome, compact cities is the only way for humans to prevent catastrophic global climate change. In fact, I do believe that. But there’s also some structural, political reasons. Let’s listicle.

1) Higher turn-out elections

It’s no secret low-turnout elections favor Republicans and development skeptics. In 2016, development-friendly candidate Sheri Gallo led development-skeptic Alison Alter on election day 17,569 to 12,943, coming within just 634 votes of winning the 50% needed to avoid a runoff. But by the time the low-turnout December election came around, Alter won out 9,481 to 5,339. It’s possible there were some voters who changed their minds but more likely development-skeptic voters were just more motivated to turn out in December. Development-skeptic candidate Laura Morrison said her strategy was to force a runoff, where the smaller, more development-skeptical electorate would favor her.

Showing up to vote for the runoff at the same location where you early voted and finding this sucks a little bit. pic.twitter.com/H7rZfcGf2k

— David Whitworth (@dcwatx) December 11, 2018

But while our two-part runoff system means we have some low-turnout ballots, it used to be much worse. Prior to 2014, we elected City Council in May elections rather than November ones. The transition to higher turnout elections has brought out a broader group of voters with a broader set of issues, less animated by opposition to development. This trend could accelerate if Texas, like Maine, adopted instant runoffs, in which voters state their second (and third and fourth, etc) choices at the same time they select their first choice, allowing a runoff without forcing voters to come out twice. However, Ed Espinoza on Twitter tells me it may take a change to state law in order for this to happen:

It was an opinion by then-Secretary of State Henry Cuellar.

— Ed Espinoza (@EdEspinoza) December 13, 2018

2) 10-1 gave more representation to underrepresented populations open to development

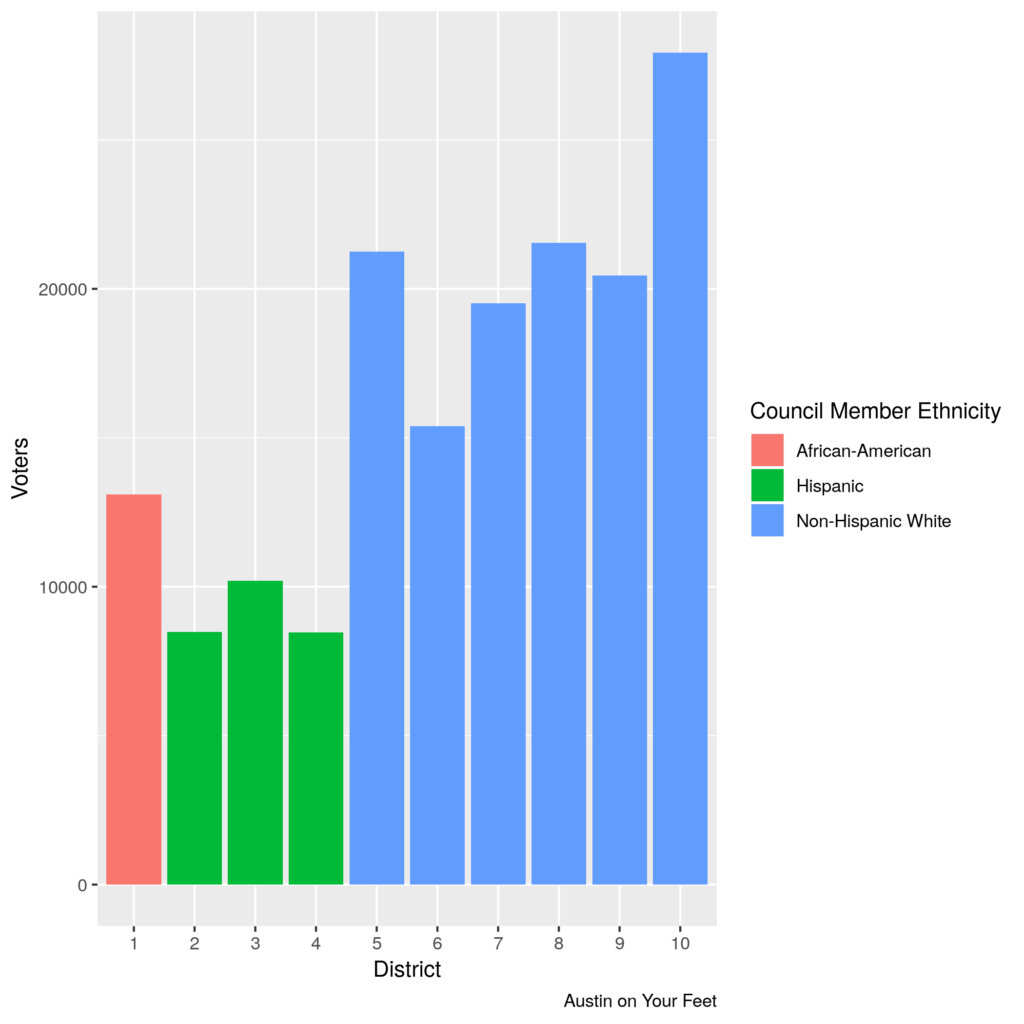

Both before and after Austin switched from seven at-large Council Members to ten single-member districts and one at-large mayor, the vast majority of votes in Austin have come from the richer, whiter parts of town. Here, for example, are the total number of voters in each district in the 2014 city council elections, as well as the racial / ethnic group of the Council Members who have represented that district:

All districts were made to have roughly equal numbers of people living in them. But not all of those people vote! There were more than three times as many votes cast in 2014 in wealthier, whiter District ten than in poorer, more Hispanic Districts two and four. This difference is driven both by the number of eligible voters and by voter participation rates. When all Council Members were elected at large, this meant that the votes of the areas and populations that turn out at lower numbers were diluted among the votes of the areas that turn out at higher numbers. Since 10-1, these areas are represented at a proportion to their populations, not to their voting rates.

Of course, it isn’t a given that “population that votes in great numbers” or “white” are anti-development or “population that votes in lower numbers” or “non-white” are pro-development. Ora Houston of District 1 was a consistent development skeptic, while Jimmy Flannigan of District 6 and Sheri Gallo of District 10 have been more development-friendly. But generally, the electeds and the electorate in the less white districts have proven to be more open to development than the whiter, more voter-rich districts–and this is true in other places outside Austin as well. Indeed, if you look at the five districts with the fewest votes in the 2014 election (one, two, three, four, and six), these districts will be represented by some of the most development-friendly Council Members on Council in 2019.

3) 10-1 created new, geographically based sources of legitimacy

Prior to the 2014 switch to a district-based council, all Council Members were elected by an electorate from across the entire city. When we were considering the switch from at-large Council Members to geographical districts, there was something of a debate on what was likely to happen between two of my friends and fellow bloggers, Chris Bradford of Austin Contrarian, who feared that this would create a system of ward privilege, and Julio Gonzalez of Keep Austin Wonky, who was a bit more sanguine. At the time, I leaned closer to Chris’ argument but so far, Julio’s predictions have turned out to be more accurate. On issues that affect a single council district, Council Members definitely defer to the district Council Member in some ways; often, the Council member whose district is most affected will speak first and longest on a case. On cases where other Council Members don’t have developed opinions, they may choose to vote with the district Council Member. But Council Members have also shown a lot of willingness to vote their consciences.

Indeed, there’s a sense in which geographical districts have actually reduced ward privilege. When the Council was elected at large, they often gave a significant amount of deference on zoning cases to leaders of the nearest neighborhood associations. While neighborhood associations are unelected, they were still often seen as a good pulse of what voters thought in that district. Now, with single-member districts, some neighborhood associations still have a large amount of sway where voters elected a Council Member that agrees with them. But in other Council districts, anti-development forces have had to handle a diminution of their authority as they put their preferred candidates to the electoral test and lost.

Nowhere has this been clearer than District 3, where Pio Renteria has won two straight elections over his sister Susana Almanza. The siblings have been on opposite sides of neighborhood politics for decades; Council Members trying to get the pulse of East Austin sentiment sometimes used extremely imperfect proxies like how many people showed up to debate an issue at City Council. Now, with voters choosing Renteria twice, there is little reason for other Council Members to value Almanza’s voice over Renteria’s.

Where from here?

Politics has a way of going through pendulum swings. It’s possible that norms of ward privilege will emerge over the course of years. It’s possible that I’m overreading the factors above and luck has played a large role in the formation of the Council. After all, the same District 1 that elected development-friendly Natasha Harper-Madison also elected development-skeptic Ora Houston. But it’s also possible that these changes in Austin’s electoral system have led to a real structural shift in politics that could have big implications as Austin becomes closer to a big city.