In this video, Council Member Delia Garza argues that downtown density is better for congestion than suburban sprawl, and Council Member Don Zimmerman argues the opposite. I call the argument for Council Member Garza. Here’s why:

Downtown, destinations are closer, reducing travel distance

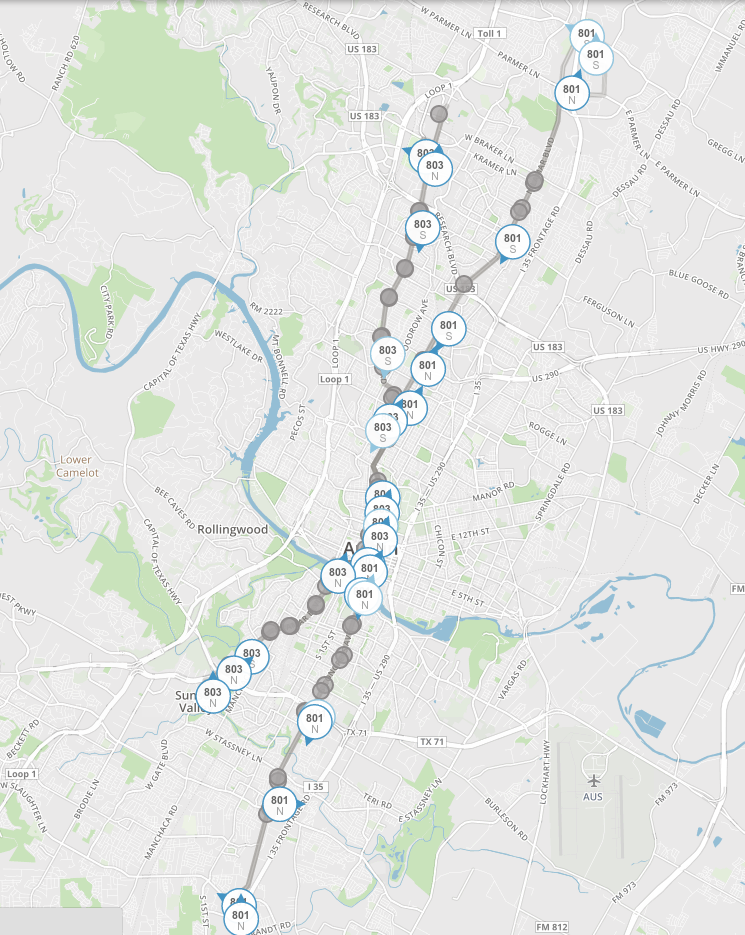

CM Zimmerman is right that one reason suburban development causes more congestion than downtown development is that suburban residents tend to drive into downtown. Austin is a downtown-centered city. More people from the suburbs come into downtown for work, business, and entertainment than vice-versa. Placing them near these destinations reduces travel distance.

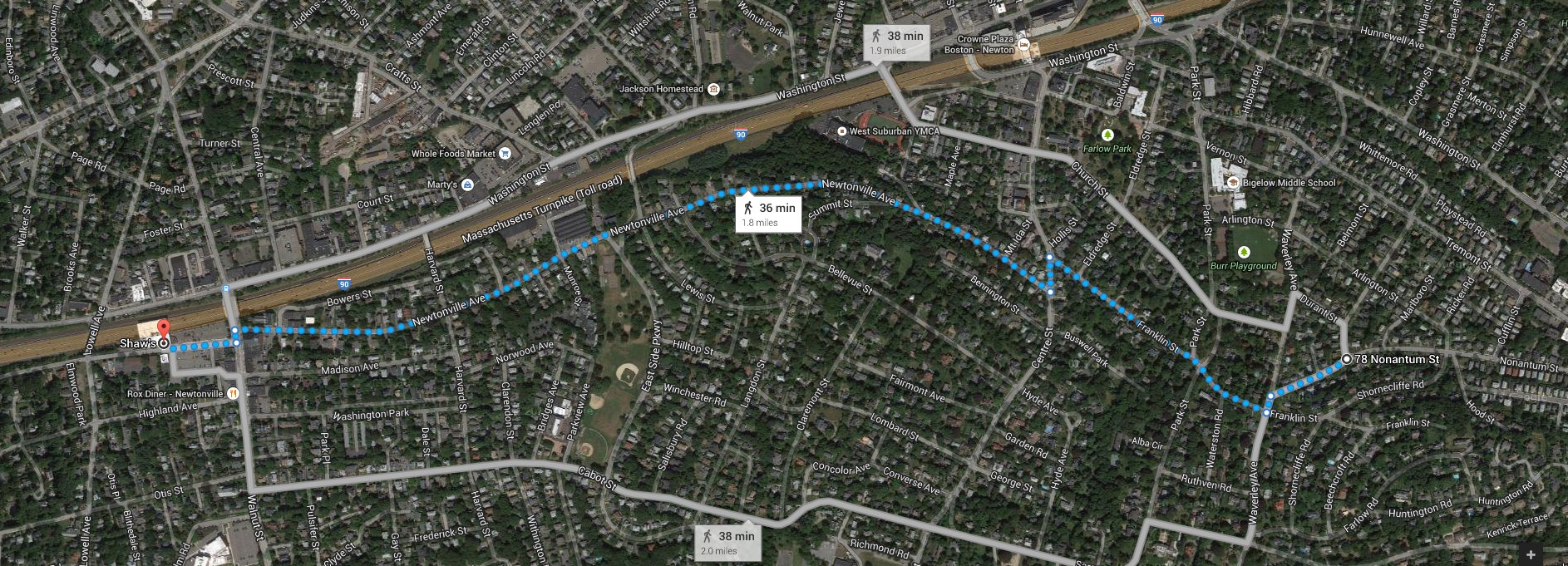

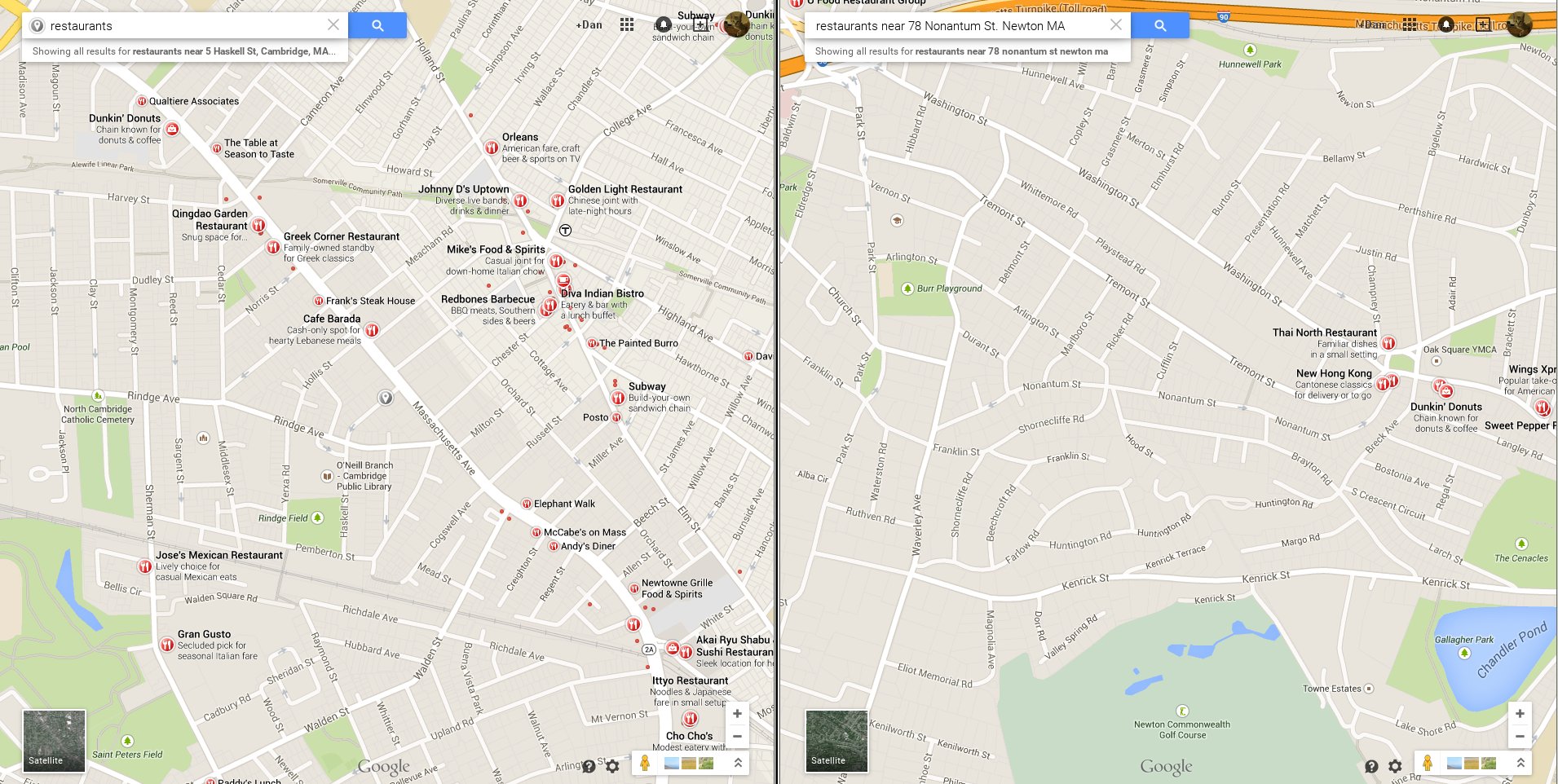

But even if downtown residents stay downtown and people on the fringes stay on the fringes, the dense development pattern downtown results in less distance spent on the roads. I spent the last weekend up on the edge of Austin, in CM Zimmerman’s district. When I stay at home downtown, there are dozens, maybe hundreds of restaurants within two miles of where I live. When I stay in District 6, traveling 10 miles for a simple night out seems normal and 2.5 miles is super close. This isn’t only about coming into downtown; even staying within the suburbs, trips are longer.

Downtown, destinations are closer, allowing more people to walk, bike, and bus

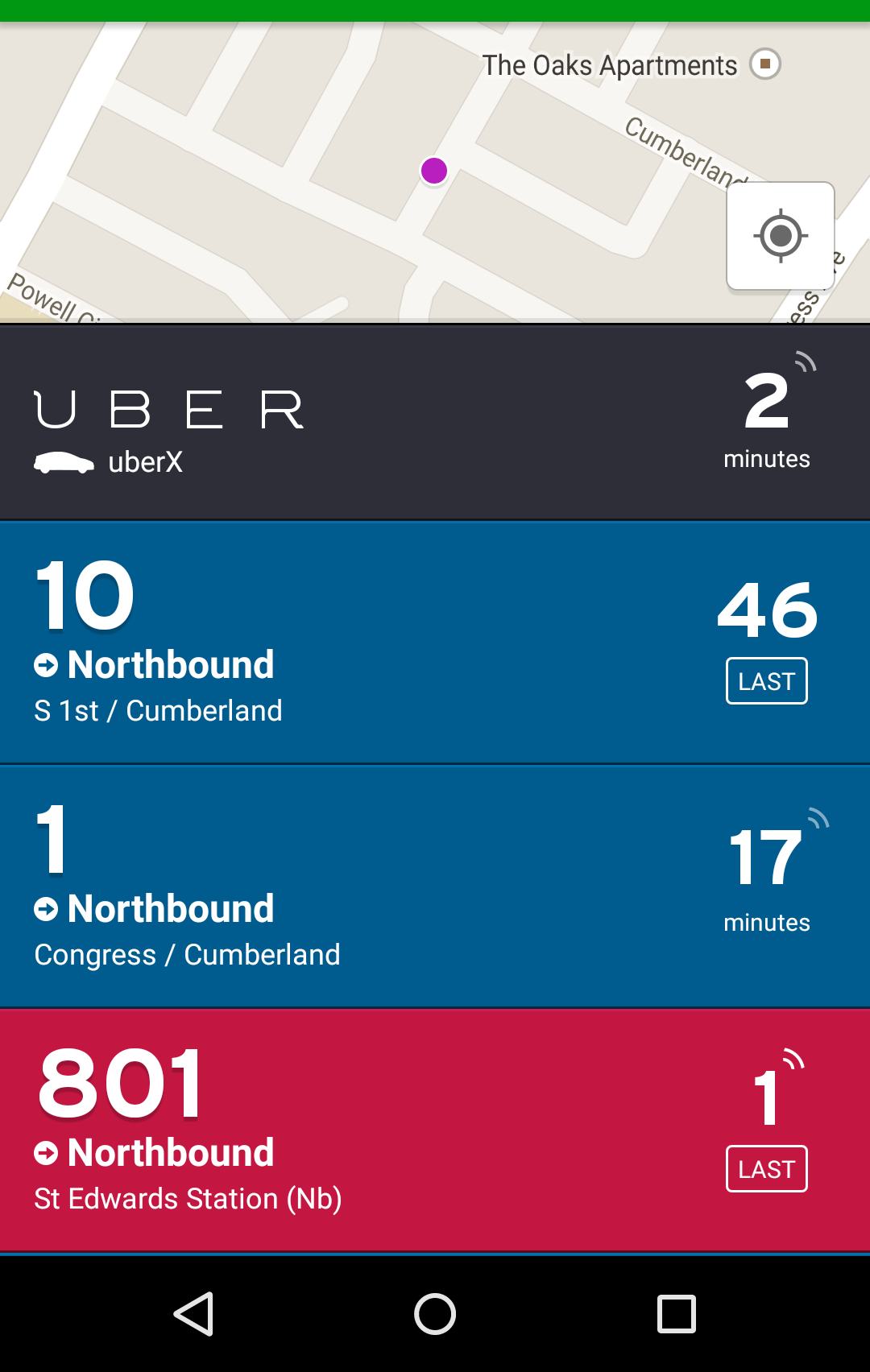

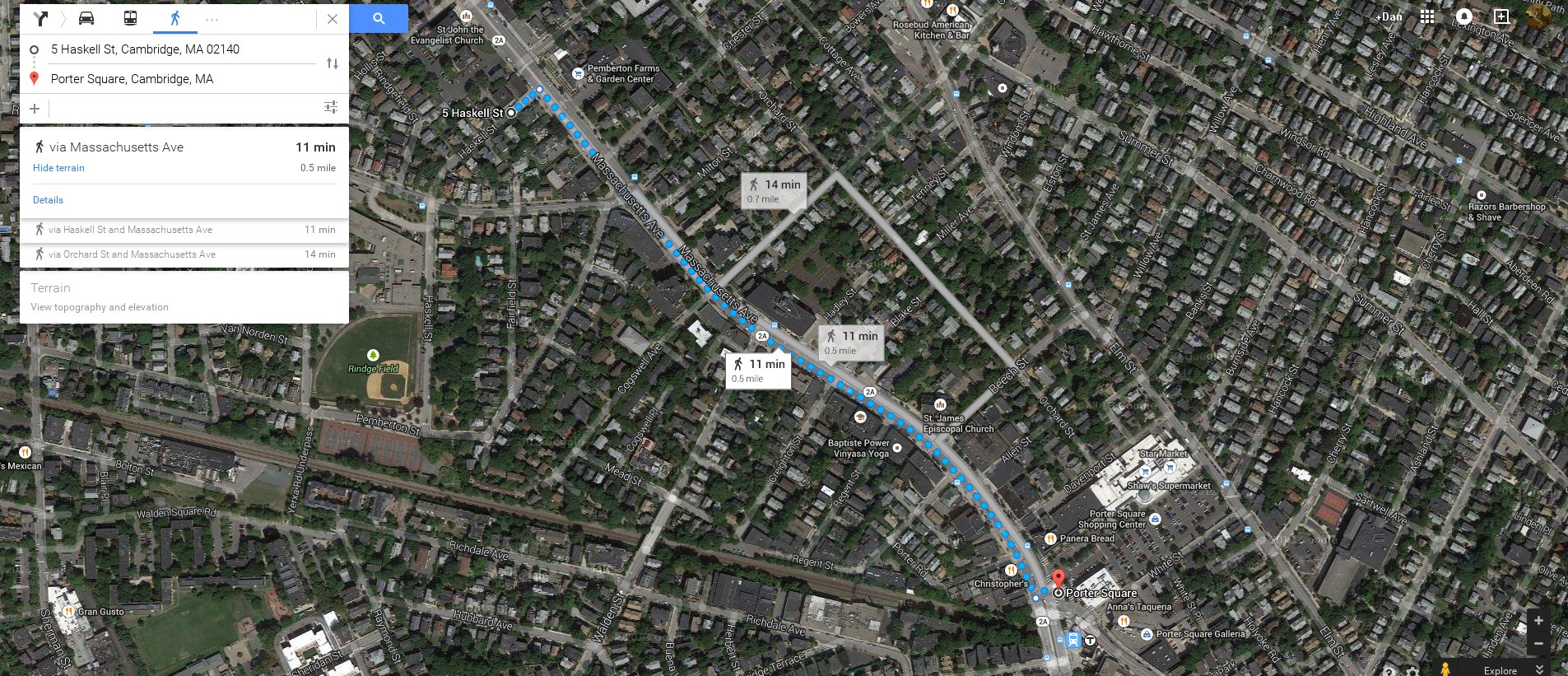

Reducing average trip distance from 20 miles to 10 miles halves the distance that somebody needs to drive. But reducing it from 10 miles to 5 miles doesn’t just halve the distance; it makes it possible for many people to bike instead of drive, using less space on the road. Reducing trips from 5 miles to 1 mile allows even more to bike and some to walk, using even less space. Bus trips are manageable where they’re short and well-served by transit. Downtown, people can choose to do without a car altogether, using very little transportation infrastructure; in the suburbs, this is practically impossible. Even for those who continue to drive cars downtown, some trips can be made on bike, on foot, or on the bus.

Downtown, uses are mixed, reducing travel distance

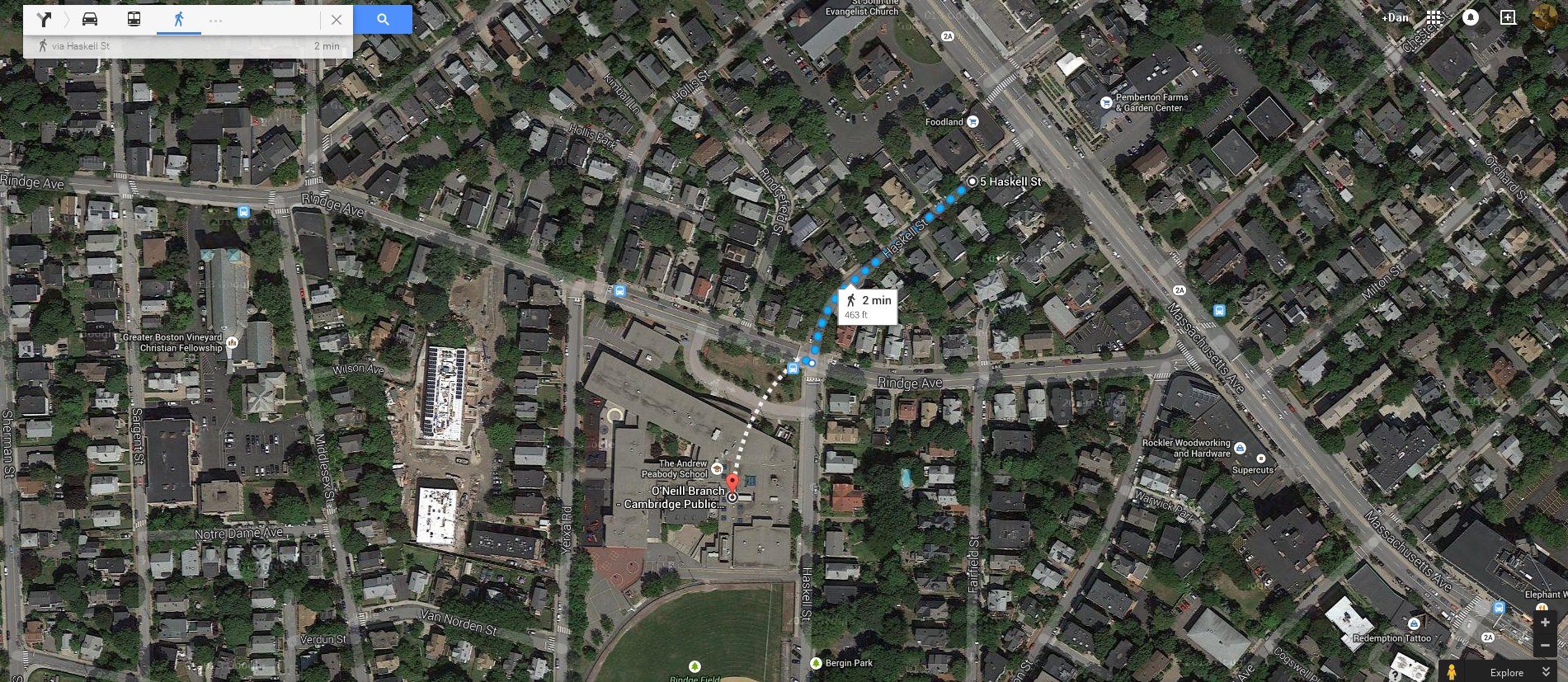

Downtown is denser: more buildings, more residents, more offices, more storefronts. But it isn’t only denser, it’s also more mixed. Whereas in some places in District 6, one would literally have to walk miles to get outside of a residential zone; in downtown, picking up the things you need is often as simple as going downstairs or around the block.

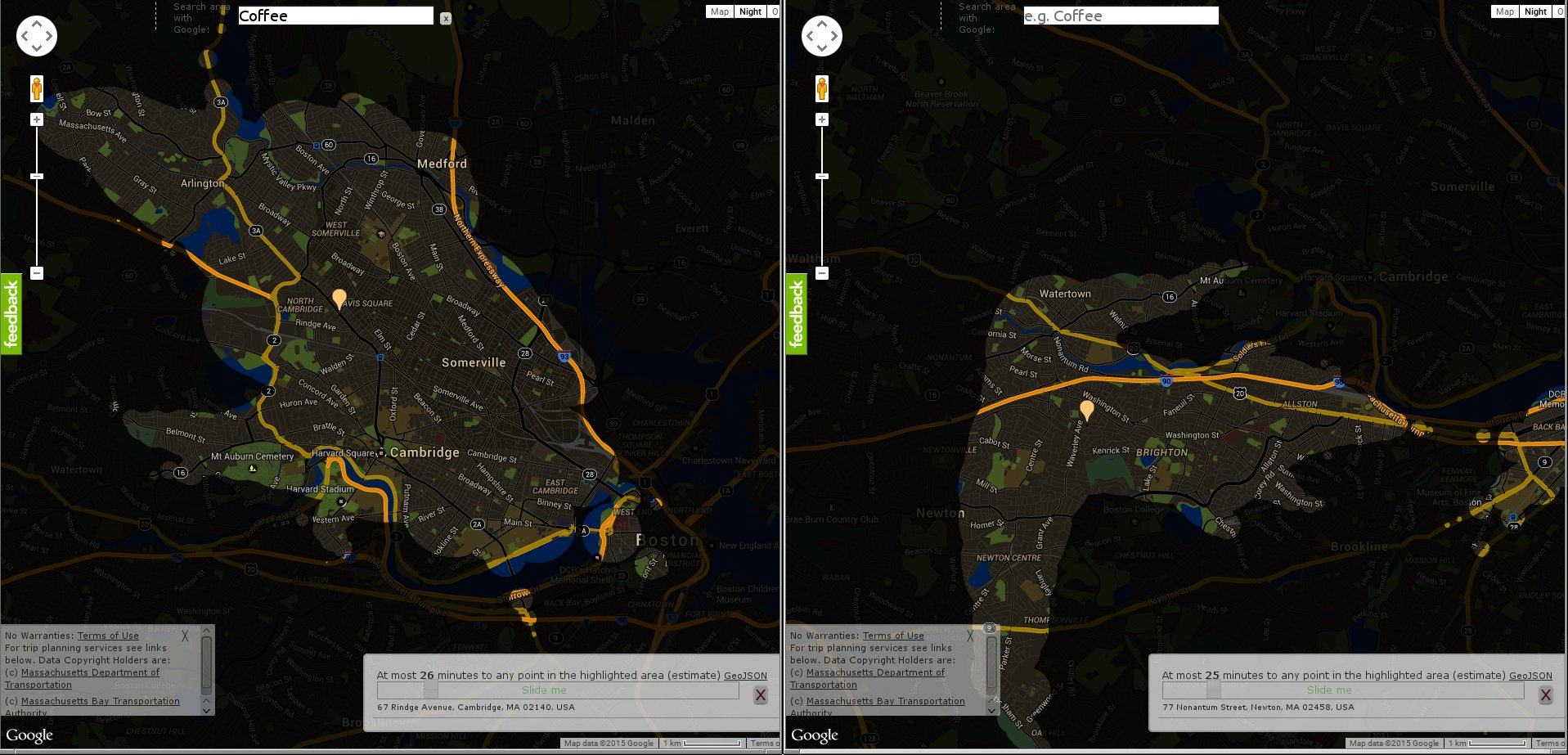

Downtown, uses are mixed, which mixes travel times

If you don’t live downtown and merely drive in and out at peak times, it’s easy to believe that streets downtown are hopelessly gridlocked. The truth is, though, that this is more of a function of people entering and exiting the area at peak hours. The Congress Ave bridge is congested northbound in the morning. South Lamar leaving downtown is congested southbound at night. But even the most congested downtown streets are often lightly traveled at other times of the day and many streets internal to downtown are almost never congested. While adding new residents in the Austonian is likely to add more people to the streets, it’s unlikely they’ll be driving into downtown at 8:30 on weekday mornings or out of it at 5. Instead, they may use their cars for errands or entertainment at times of light traffic.

This argument was framed as dowtown vs. fringe development but those aren’t the only two options

In this discussion, CM Garza and CM Zimmerman were only comparing dense downtown development to greenfield development on the fringes of the city. But those aren’t the only options. Moderately dense central city infill development poses many of the same benefits that high density downtown development does.