On Thursday night, City Council chose to endorse Project Connect doing a detailed study of an urban rail route running from somewhere along East Riverside to somewhere near Highland mall. At the same time, it declined to request a similar study of the East Riverside to North Lamar (via West Campus) alternative. As regular readers of this blog know, my analysis of the data led me to prefer the latter. But Thursday was the last opportunity for West Campus / Lamar’s inclusion in a November bond election. Going forward, I will be focusing on some of AURA’s remaining goals. Today, however, I’m going to look backward and do a little retrospective on things that stick out to me of the previous few months.

Emergence of a new (not “New”) urbanist community

The growing community of folks centered around AURA were often glossed as being “pro-transit” and the debate at Council as representing a “divide in the transit community.” Pro-transit was a term AURA often used ourselves. (I say “ourselves” as I am an executive committee member of AURA.) But I think “pro-transit” has caused a lot of confusion.

An Urbanist Perspective

A better term for this community’s common perspective is urbanist. Not just any urbanism, either, but an urbanism influenced by ideas of market urbanism. This perspective takes on a long list of issues from liberalizing zoning to pricing parking to allowing short-term rentals to improving transit to allowing urban farms. Some of the same folks discussing urban rail were involved in issues like opposing rental registration, extended parking meter hours, or specific zoning cases like TacoPUD. The (market) urbanist perspective generally believes in light-touch city regulations. While urbanists believe there’s too much space around Austin dedicated to parking, the policy tool we reach for is not city regulations against parking, but removing city regulations that require building parking. While urbanists enjoy density, we don’t strive to prevent people from choosing to live in low-density suburban areas. We object to zoning that requires central neighborhoods to remain at low densities, as well as regulations that subsidize suburban living over urban living. Similarly, we tend to think that even in large parcels like the Mueller development, the city should have a lighter touch: lay out a connected street and utility grid and let the neighborhood develop organically instead of master planning a giant community down to minutiae of aesthetic decisions. This is a short, bad treatment of the variety of flavors of urbanism and I have perhaps done a disservice to the majority urbanist opinion on one or more of these issues. But The point I’m making here is that the thing that unites this community is not (merely) our shared love for riding transit, but our shared vision for the future of cities.

Urbanists on Transit

This urbanists’ community’s perspective on transit, while generally far more in favor of it than the average Austin resident, is much more complicated than simply “in favor.” Urbanists tend to fall into Avon Levy’s technical camp, seeing poor-quality, poorly-used, or poorly-managed transit as just as strong an obstacle to good transit as the general anti-transit political climate is. To take my perceptions: I believe MetroRapid is a decent project that found federal money to make incremental improvements to all buses in Austin, even if its badly oversold and may have played a lamentable role in preventing what would’ve been a fantastic rail line on Lamar. On the other hand, I see MetroRail as an inefficient subsidy for suburban living, because Capital Metro spends so much more per suburban MetroRail passenger than it does per urban passenger, and additionally because the vast majority of the MetroRapid MetroRail operational budget is paid for by CapMetro, thus operating in a zero-sum, fixed-pie competition with funding for urban transit. This ties into the general urbanist idea that there’s nothing wrong with choosing to live in the suburbs, but it shouldn’t be so heavily subsidized. The point I’m making isn’t the particulars of the argument on particular lines; the point is that the urbanist community focuses as strongly on the quality of transit as it does on its existence.

Other pro-transit voices feel betrayed

At the Council meeting, I saw many pro-rail folks seem to feel betrayed by, as they saw it, the spectacle of supposedly “pro-transit” people announcing opposition to a transit line (the Highland proposal). Many of the speakers in favor of the Highland proposal emphasized that they were disappointed in the route themselves, but they were team players who believed in transit, no matter where it goes. A statement supporting rail no matter the route was relayed from the Austin chapter of the Congress for New Urbanism, and the sentiment is well-summarized in my friend Stephanie Myers’ column for the Austin Post. The implication was that those who opposed the Highland route were not team players. Outside Council chambers, the discussion was considerably more heated. The word “selfish” was relayed to me as a description of those urbanists who oppose Highland, because we are demanding transit be on our terms alone. A debate on Twitter emerged over whether, should the bond election fail in November, the primary blame for it should fall on AURA, for prolonging the debate over route choice.

Both sides need more communication on urbanists’ goals

But, to me at least, the criticism doesn’t sting very much. When somebody is playing a dangerous game of chicken, in which they pretend to oppose a route they actually support in order to force others to get behind the route they support even more, it’s possible to shame that person into backing down and agreeing to compromise on the first option. But it’s much more difficult to shame somebody about signalling their true opposition to a plan they really do oppose. That, I believe, is the case with the anti-Highland activists. They (we) simply believe the Highland route is a negative for the city*, so we will oppose it. We don’t oppose the Highland route out of vindictiveness or disappointment, but simply because we believe its bad policy. No amount of telling people that they’re selfish or “hurting rail” will get people back on board for what they believe is bad policy. Nobody is ashamed to be the reason a bad project failed.

I do feel bad, though, that AURA’s messaging seemed to have failed to get our position across, leading many people to feel misled. When AURA said, for example, that it stood for a successful urban rail project, I always took that to mean that our goal was to see an urban rail project with high ridership at the center of a walkable, urban central Austin. Although I still think that’s possible if we start on Riverside first, for many of those who spoke at Council, the possibility for a successful urban rail project died on Thursday. Although it’s always dangerous to assume what others think, my impression is that others read AURA’s goal of having a “successful urban rail project” as meaning “passing a bond with money for rail.” Understandably, they feel misled when AURA supporters threaten to vote against a bond, as that would clearly violate what they believed we said we wanted. I believe many would have been able to better anticipate AURA opposition to Highland if they had believed AURA to be a fiscal responsibility watchdog who would only support an urban rail project with anticipated subsidy / ride below $X.

AURA is not a “pro-Lamar group”

Similarly, I believe that many of the people in the Council chambers on Thursday believed AURA to be a “pro-Lamar” group in the same way that the speakers who lived in Mueller were “pro-Mueller” or that two of the other “anti” speakers (Scott Morris and Lyndon Henry) are. While its true that many of AURA’s supporters came to the conclusion that Lamar would be a fantastic location for an urban rail route–some before and some after the release of public numbers–few of us live and work along that route. Zero of AURA’s four executive committee members would take an East-Riverside-to-Lamar route as a commuter. I am the only one who lives near the route, but I live downtown so I’m near all routes under consideration and I work to the west, not north. I struggle to think of more than one non-student member who would be personally served by the route. We supported Lamar because of our belief in its success, rather than because that’s the neighborhood we represent. Despite the fact that inclusion of Lamar was one of AURA’s prime goals for this last Council meeting, we have other goals. I believe I actually heard more support for East Riverside from those signed up “against” the item than from those signed up for! AURA’s goals, stated plainly in the resolution linked above, include a lot of goals that have nothing to do with Lamar and instead focus on trying to make the route as successful (by our use of the term) as possible. I do hope that others who are working with us see those goals and work with us to accomplish them.

Urbanists need a new Organization

For urbanists, I think the real lesson to be learned here is that the time for building an urbanist advocacy organization in Austin is now, if not sooner. There may be far less confusion about the position of the Transit subgroup of #ATXUrbanists than there was about Austinites for Urban Rail Action.

What does “Data-Driven” mean?

The other big area of confusion in the last few days for me has been the issue of a “data-driven process”. There is clearly a large gap between what I took this to mean and what many others involved in the process mean by the same words. Neither AURA nor others fully defined what it means, but I’ll do my best to parse what I see the differences are. My overall impression is that for AURA, data-driven was shorthand for “give enough data and analysis to let the public and decisionmakers make their own, informed conclusions.” For many others, I believe data-driven was shorthand for “make a decision in an unbiased way.”

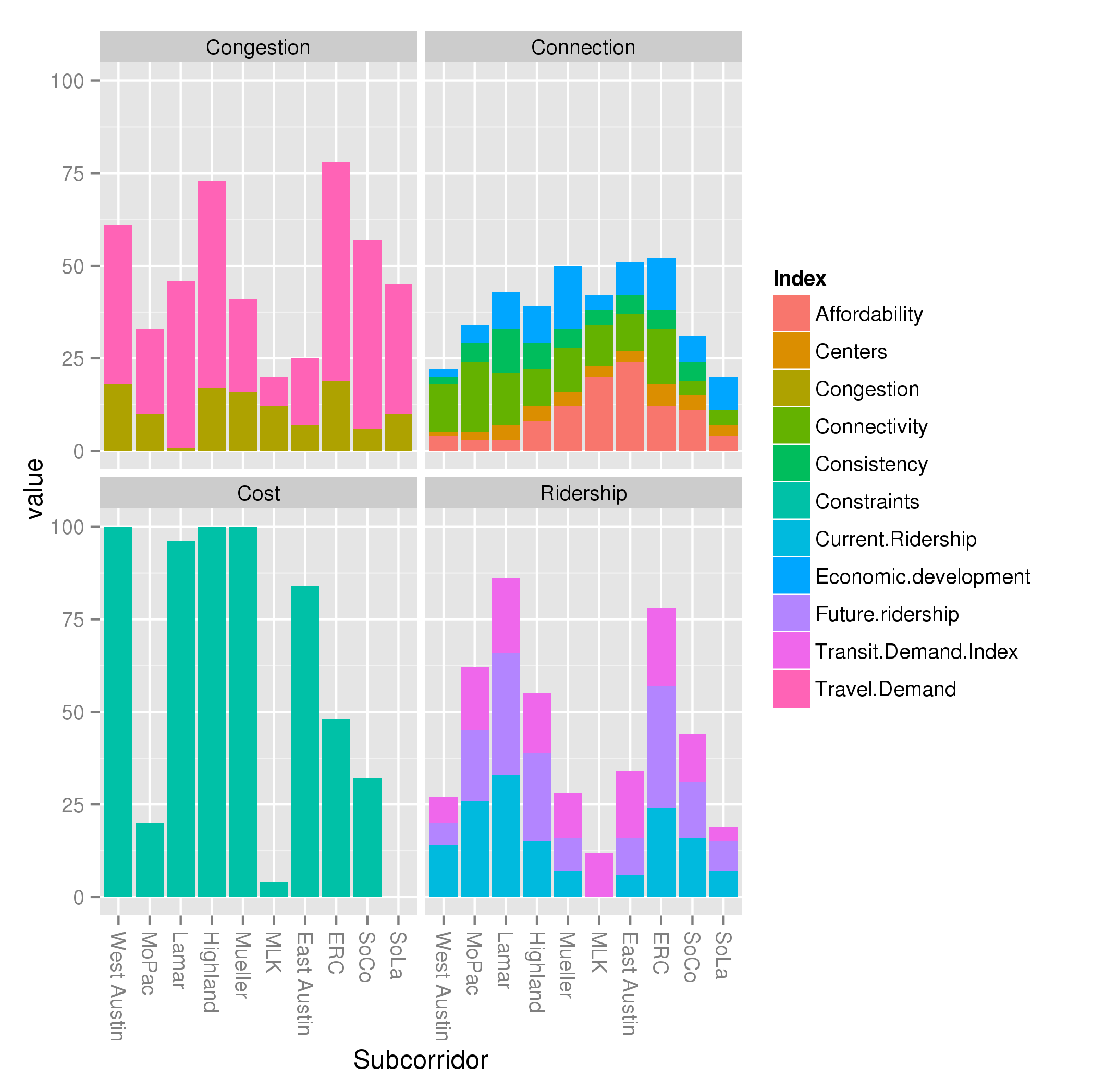

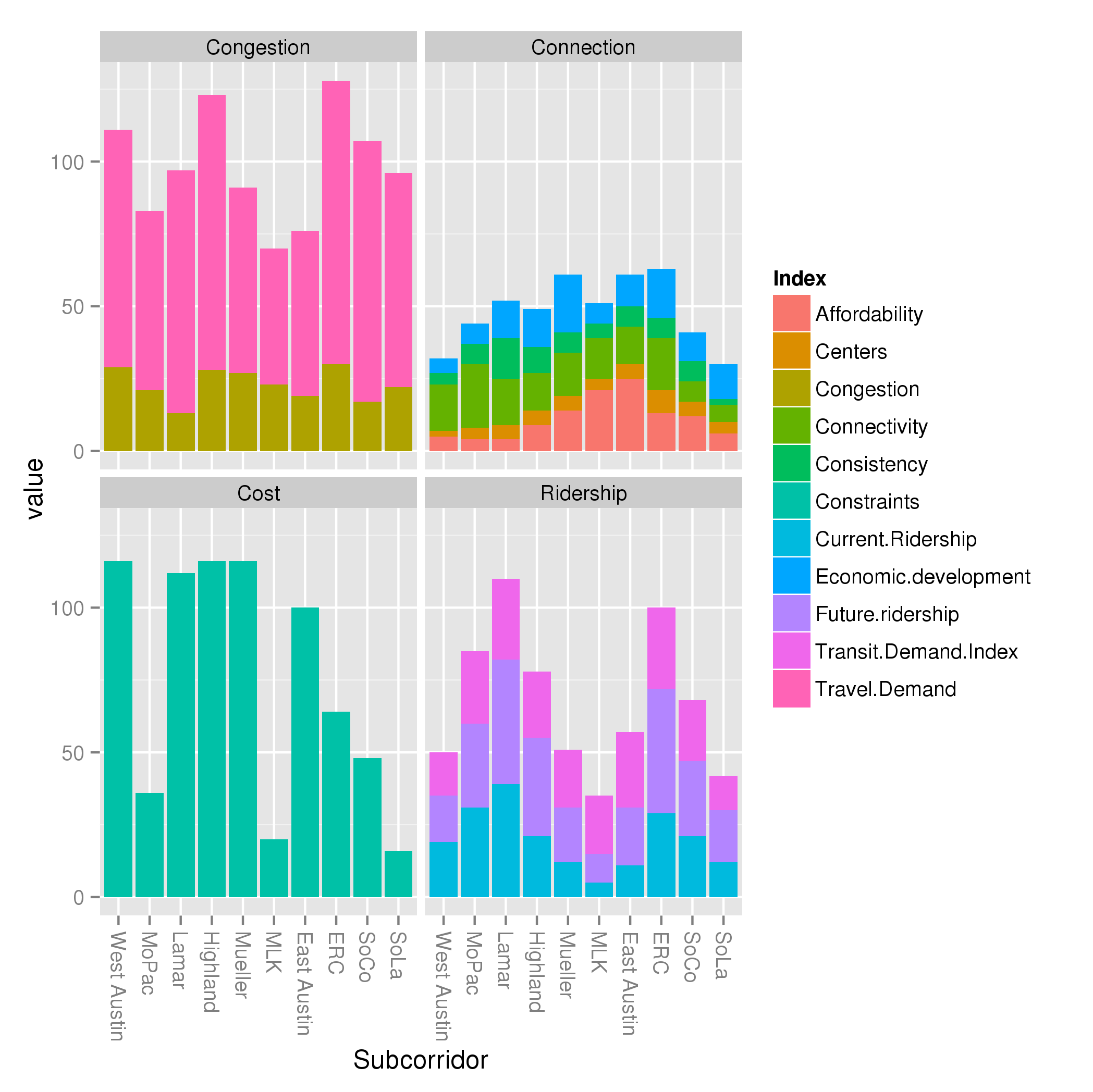

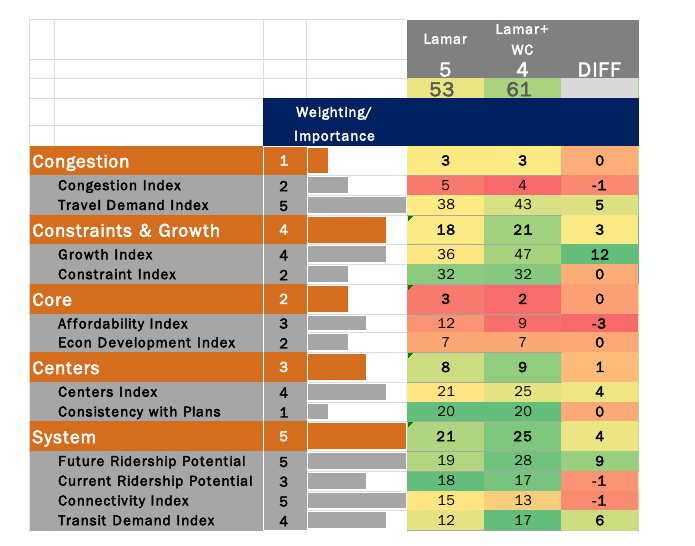

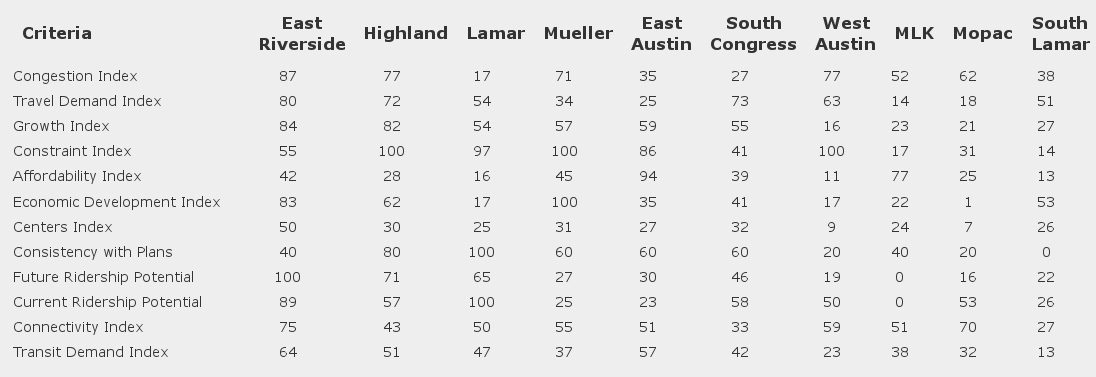

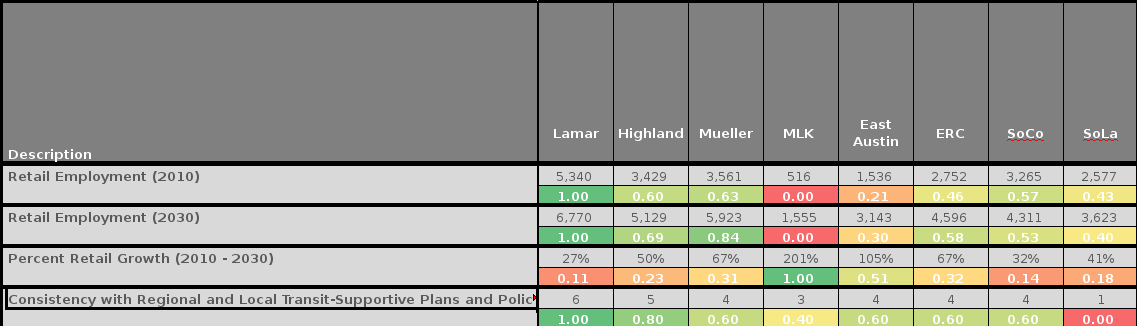

AURA, for example, from before the process even started, requested an iterative process from Project Connect, in which data and analysis were released at checkpoints in formats that the public could play with and draw their own conclusions. This did not happen, at least not as I see it. An extensive dataset with West Campus and no-highway alternatives was in fact released in a format that allowed manipulation, but three weeks after Project Connect’s final recommendation was made and just one week before CCAG was to make its decision. Even then, it took me hours to figure out how to bypass the copy locks on it and I never did manage to figure out how to copy their formulas, though they were not difficult to reverse-engineer and reproduce. Project Connect’s public website, in which they asked people to weight criteria indices themselves, did more to frustrate than inform. Rather than giving the public information about the data driving the decision and then letting them decide, Project Connect sought information from the public and then told them what outcome they should want.

I received some negative feedback for doing an independent analysis of the data. This is a criticism that makes perfect sense in the “data-driven = fair” mindset: the decision had already been made by the time I started my analysis. As there was no evidence (in their mind) the decision was unfair, my decision to do independent analysis was evidence that I in fact was biased, and merely trying to come to my own pre-determined conclusion as sour grapes because my preferred route wasn’t chosen. In the “data-driven = let the public decide” mindset, this criticism is bizarre. The whole point of having a data-driven process was to enable exactly this type of independent analysis. I was merely making good on the promise of being data-driven in the first place.

Similarly, I was surprised to hear many members of CCAG praise Project Connect heavily for the strength of their analysis immediately on receipt of the final recommendation. Not because I thought the analysis was poor, simply because I was still waiting for analysis to be presented. In the “data-driven = unbiased” mindset, the burden on the project team was to show that they really did take all routes seriously, and that their methodology wasn’t intentionally tilted toward a predetermined outcome. The sheer volume of numbers used showed that they really did apply their methodology to many different routes.

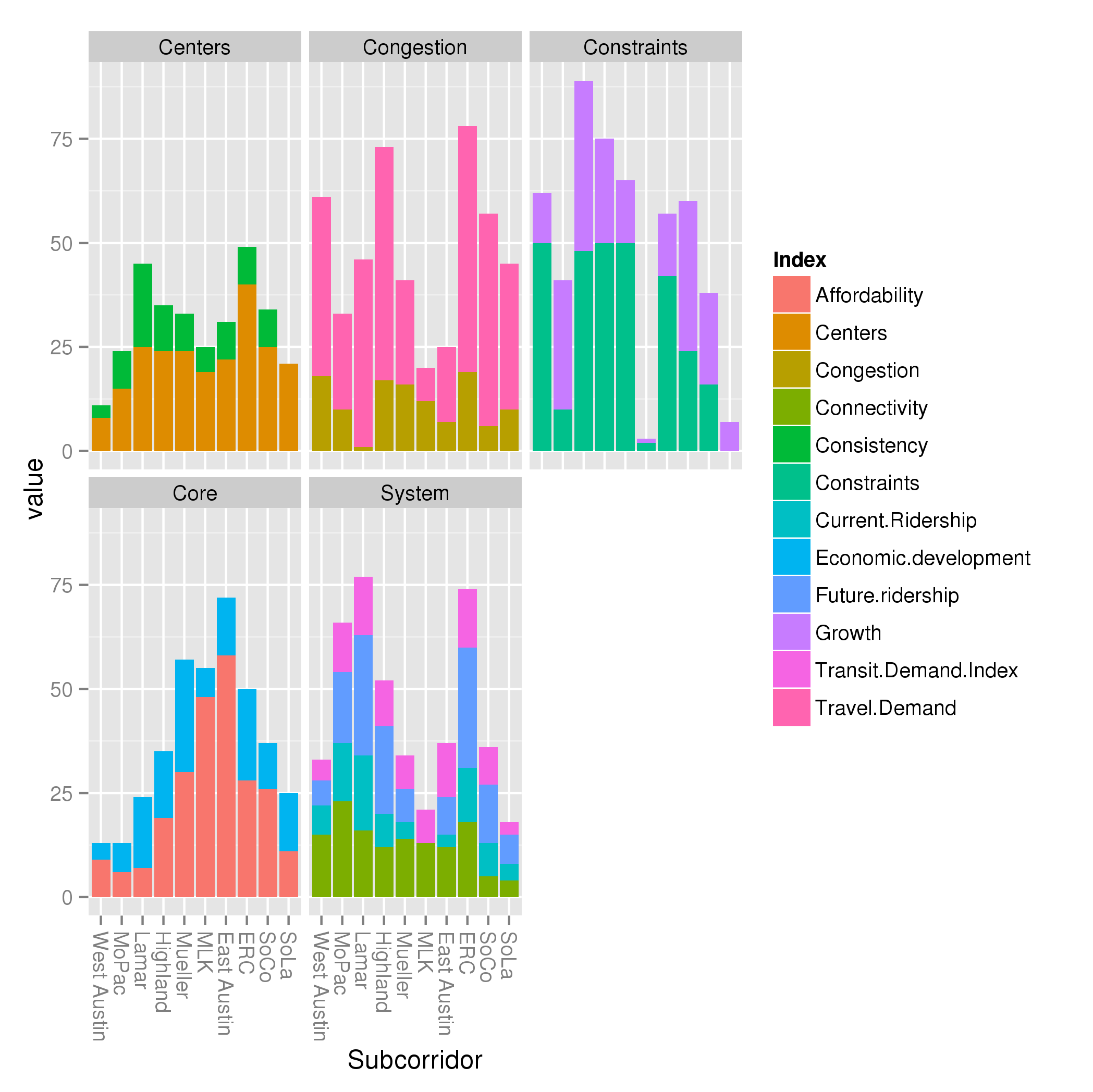

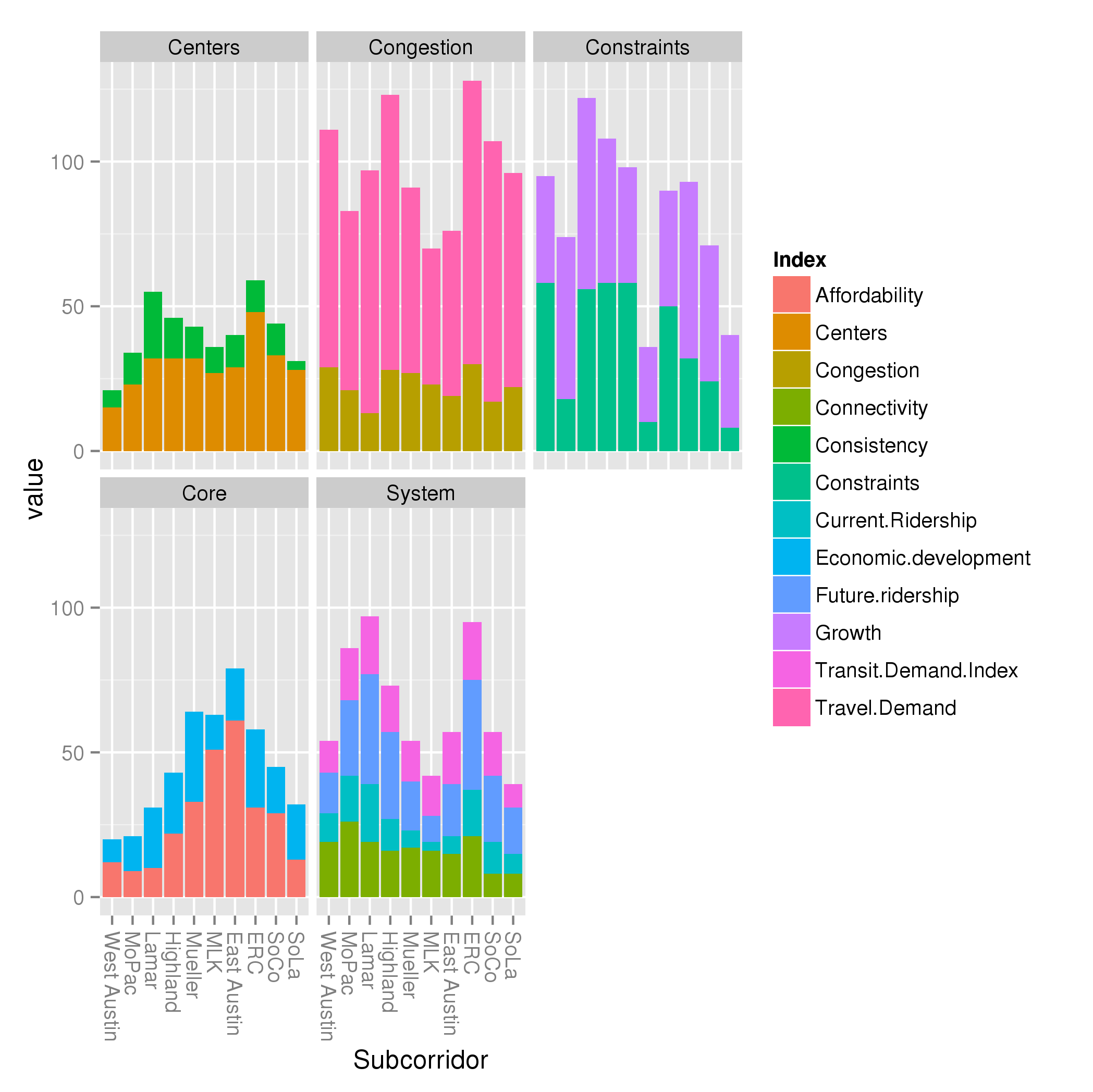

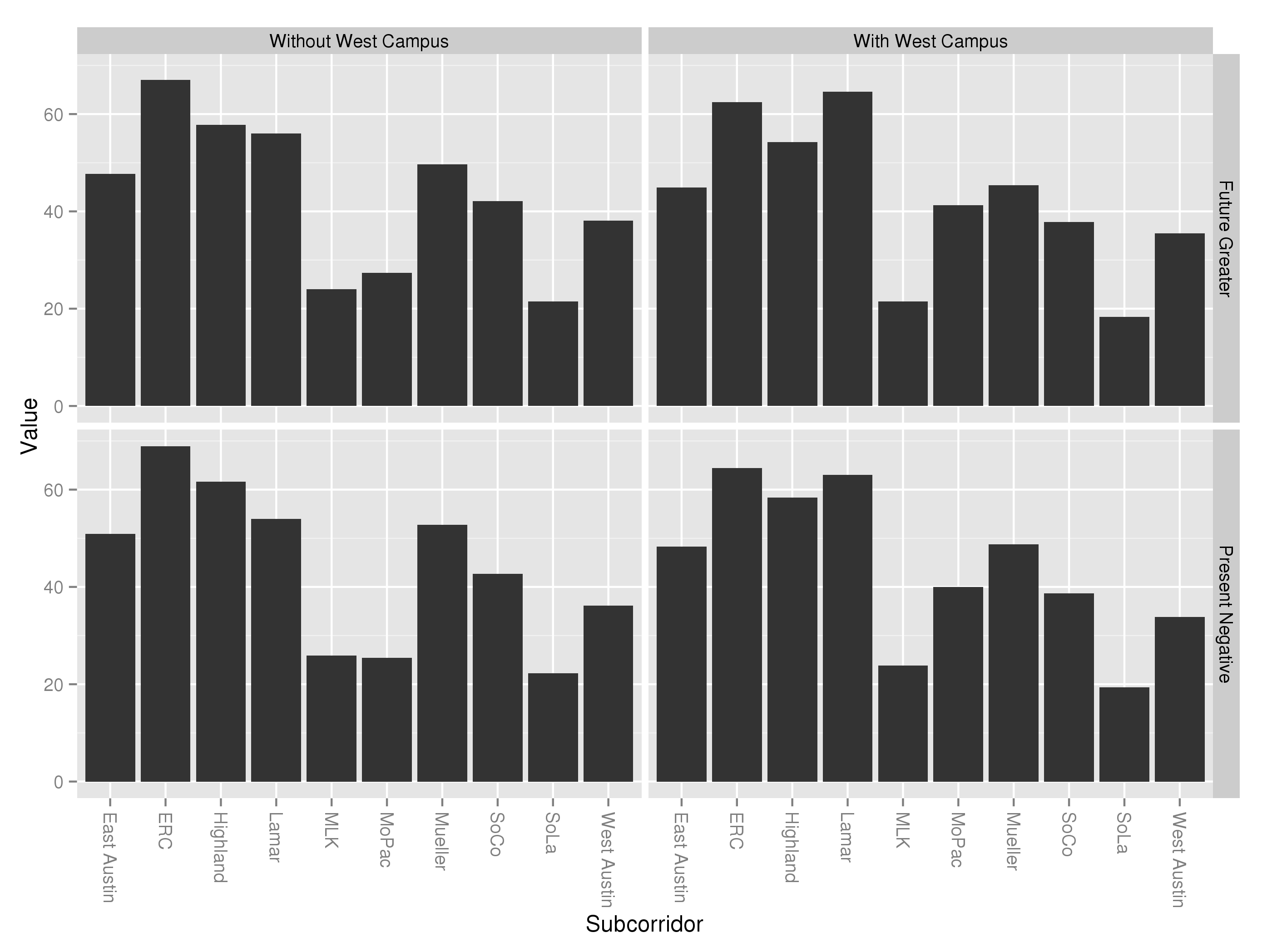

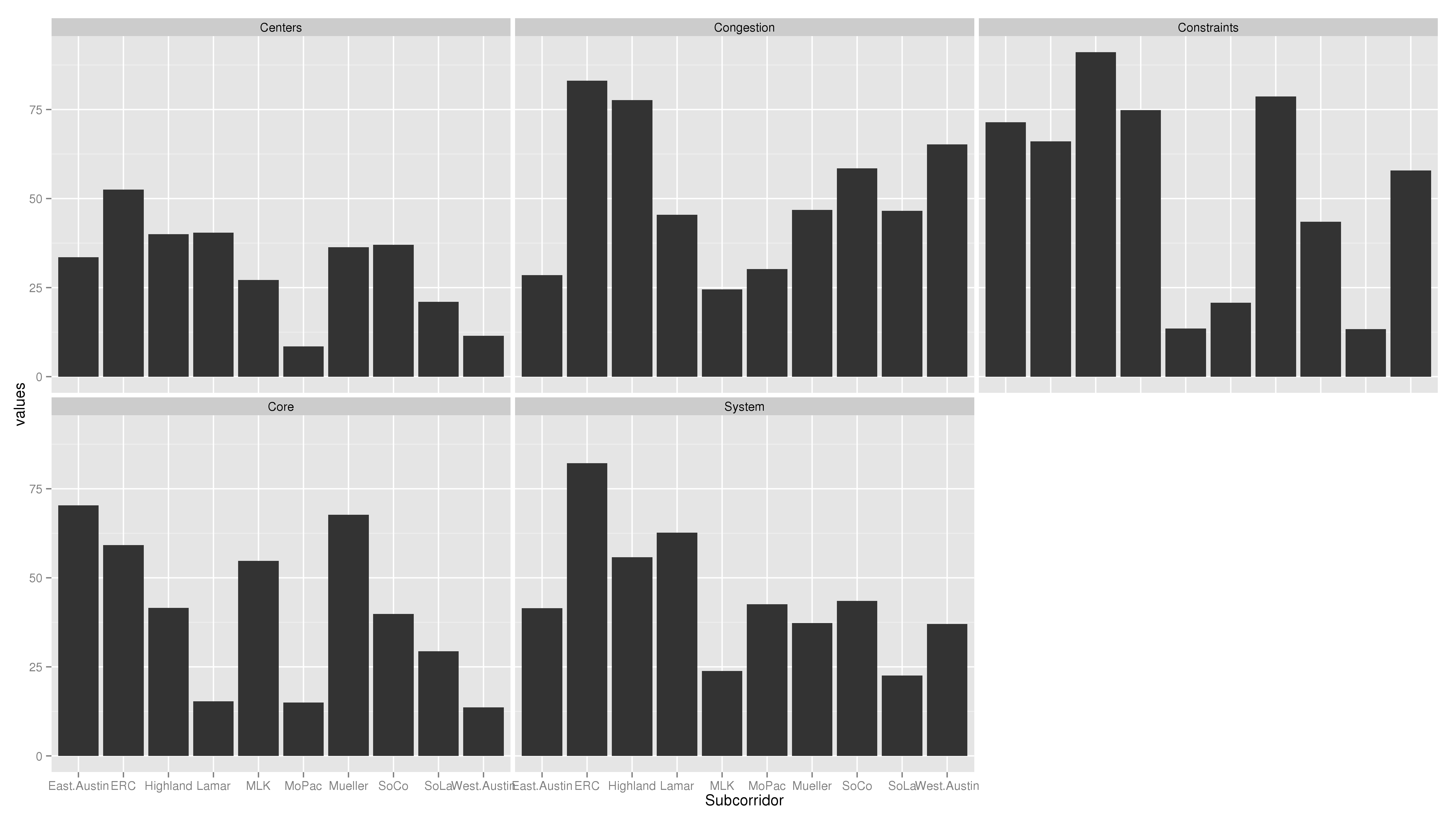

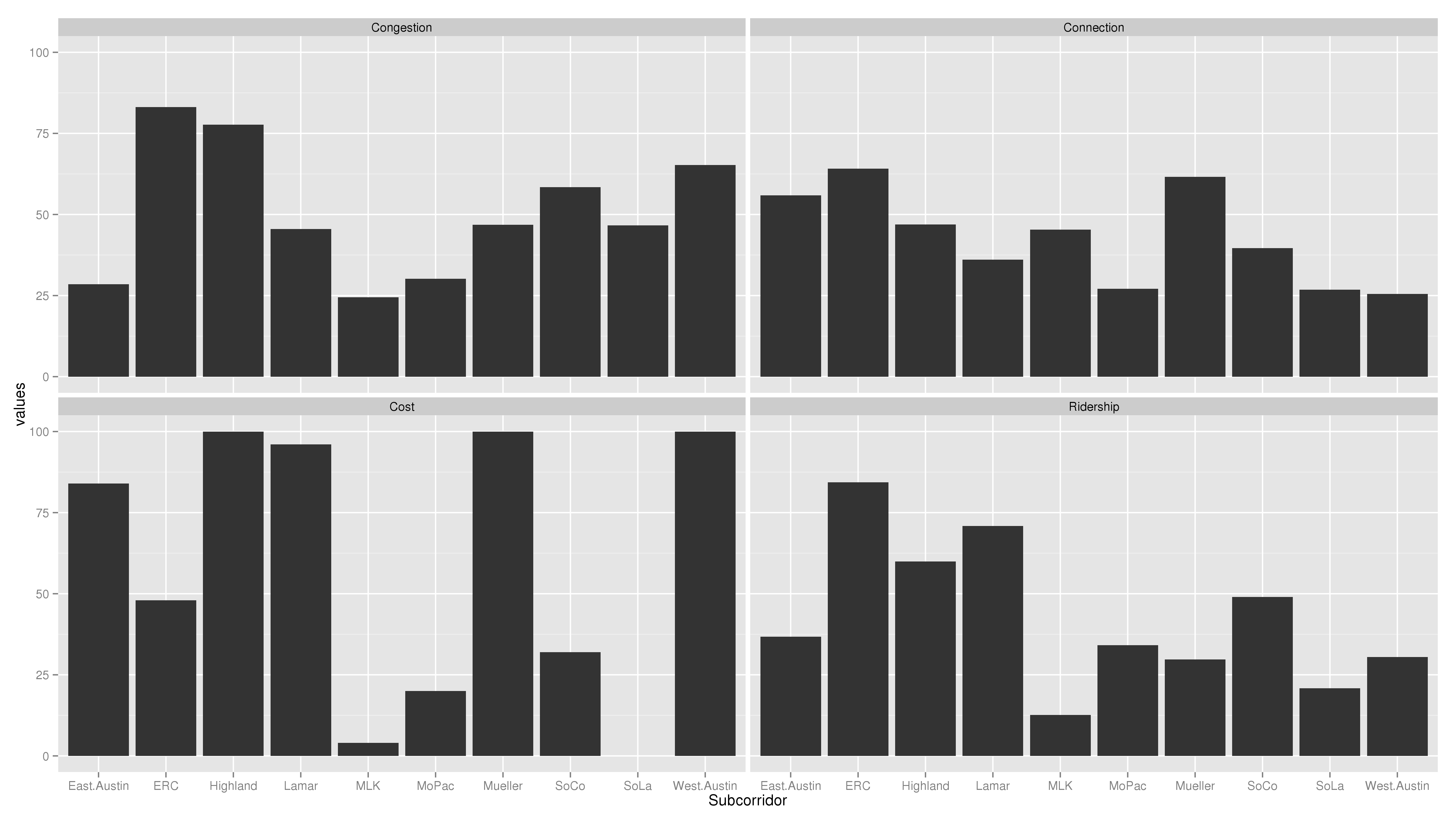

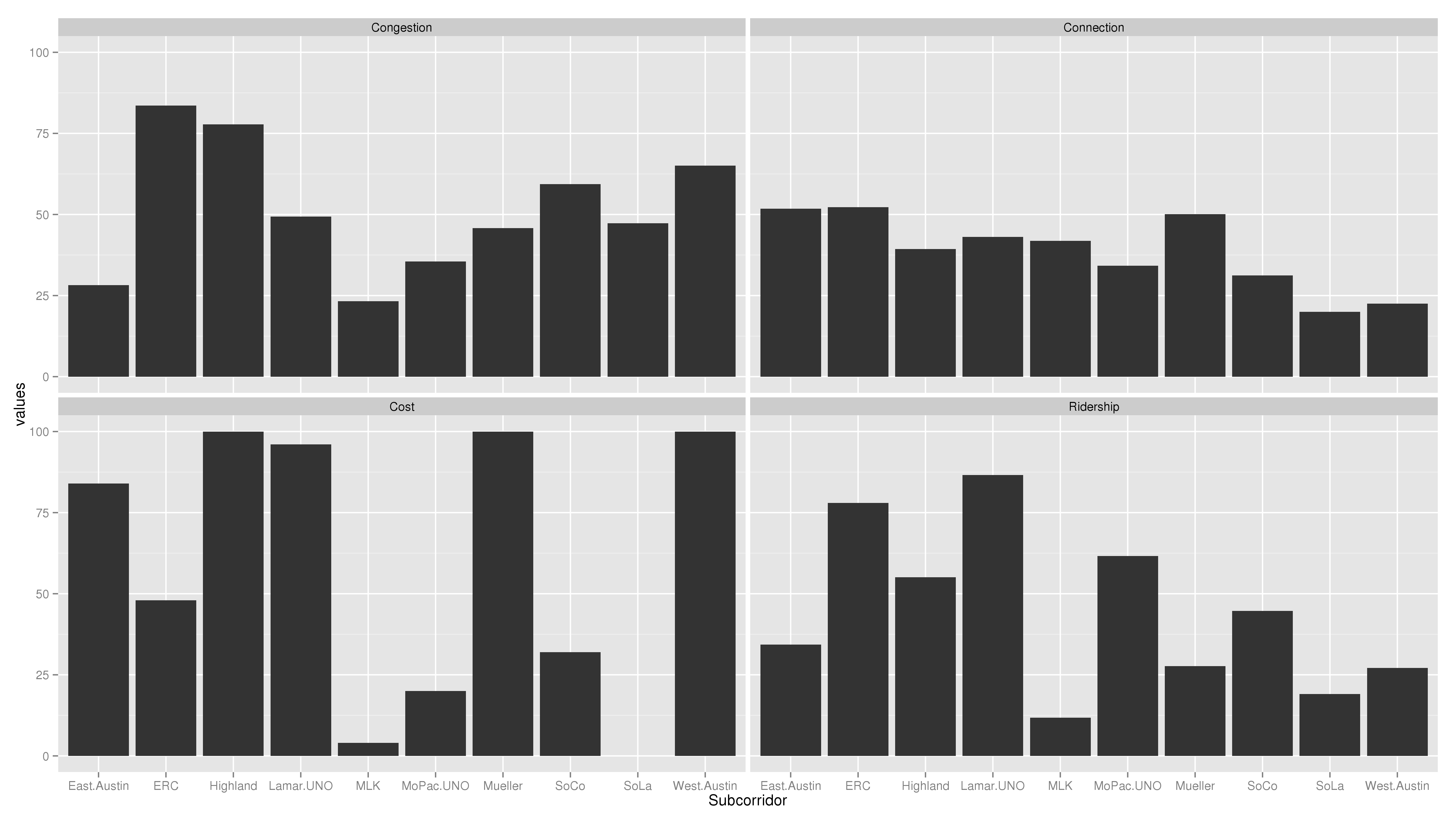

In the “data-driven = inform the public” mindset, though, the important thing is for the staff to prepare enough information that, even if they included no final score or recommendation, the decision-makers would be able to decide for themselves. What route would be best for ridership? What route would relieve the most congestion? How much would they cost to build? These are factors that the project team did consider internally, but I do believe that my cursory 20-hour analysis of the data may have presented far more digestable information about how each route scores on the different metrics than Project Connect did in any report. Project Connect did present alternative weighting scenarios. This fits with the idea of attempting to prove that their weightings were done in an unbiased way. However, I was less interested in divining a final score than in looking at each of the metrics to understand what the numbers meant for how the different subcorridors would differ on the ground.

Again, I think that this is an area AURA needs to be far clearer on. I’m not entirely clear what “data-driven” means in my own head beyond “I know it when I see it” and we have, for the most part, failed to articulate what the advantages of our flavor of the policy would be.

Going forward

I’m very excited for the future of this emerging urbanist community. I have met many fantastic people both in, around, and completely outside the community through this process. The process has uncovered many of this community’s strengths: analytical skills (if I do say so myself), social media presence, and, most importantly, we struck a nerve with a large corps of folks who feel unserved by the current political process. But it has also uncovered many of our weaknesses: we did a much better job of communicating to our supporters than to others in the process, let alone the general public. We lack a solid organization and all the perquisites that come with that. We lack much in the way of support in City Hall. Many of our supporters feel jaded or angry, something that I think comes from being both interested in city politics and feeling unrepresented. These are all things a new urbanist organization can improve on.

* I believe that I find myself more in favor of the Highland route than many of my fellow activists. I share the opinion that it would simply be a terrible project as a first leg. But I do believe that, for similar reasons as Levy discusses here, it could be cost-effective as an extension to a successful Riverside-UT line.