So this happened last night (since deleted):

And this too:

Residential Permit Parking is ostensibly to allow residents to find street spaces near home in areas where parking is super competitive. In practice, though, few residents park onstreet during restricted hours and most of the parking goes unused.

It’s a phenomenon very easy to spot near the South Congress commercial strip:

Residential permit parking 1-2 blocks from S Congress. This is waaay underutilized. pic.twitter.com/NzomYZ5an7

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) May 11, 2015

But it happens all over the city, wherever we create resident-only zones. Clay Avenue off Burnet:

@DanKeshet Looking north on Clay Ave just north of Houston. RPP says no parking anytime without permit pic.twitter.com/KYTPaHjgtQ

— Mary Pustejovsky 😷 (@mpusto) January 4, 2015

A few blocks west of that, Montview Avenue, also off Burnet:

On Fortview, near Manchaca. Note how the unused parking starts where the residential zone starts.

On Daniel Drive, one street over from Barton Springs Rd:

Some RPP zones in Mueller (all via Mateo Barnstone):

And near South 1st (again via Mateo Barnstone):

Do you have pictures of street parking going largely unused once designated as residents-only? Tag them with #NoParkingInRPP on twitter or add them to the discussion on the Austin on Your Feet facebook page.

If you watch enough zoning hearings, the testimony begins to sound pretty repetitive. That novel argument you’re making? The Council members have heard it a million times before. Here are 9 of the things we hear most often at zoning hearings, illustrated by cats.

Those 1,000 times you sat on your couch to support developments far away from you surely counterbalance that one time you came out to oppose your neighbor’s development.

If you’re opposed, just tell us why; don’t go on about how you’re not a person that opposes things.

The city notifies neighbors and registered civic organizations about upcoming permits. Developers seek out people they think might be affected. But it’s hard to know who is going to care and notifications are often thrown out. Don’t feel left out! If you’re at the hearing, you’re being heard. Just say what’s on your mind.

The city notifies neighbors and registered civic organizations about upcoming permits. Developers seek out people they think might be affected. But it’s hard to know who is going to care and notifications are often thrown out. Don’t feel left out! If you’re at the hearing, you’re being heard. Just say what’s on your mind.

Usually said while proposing somebody build more parking. If you want that reality to ever change, you have to accept building less car infrastructure.

Land development is a business. Like all businesses, sometimes you make money and sometimes you lose money. You just try to make sure that you make enough money on the winners to cancel out the losers. Focusing in on the fact that the developer is hoping to make money makes your testimony sound more like you oppose out of spite than a particular reason.

Land development is a business. Like all businesses, sometimes you make money and sometimes you lose money. You just try to make sure that you make enough money on the winners to cancel out the losers. Focusing in on the fact that the developer is hoping to make money makes your testimony sound more like you oppose out of spite than a particular reason.

If council members haven’t learned economics by now, they’re not going to learn it from your three minute testimony.

If council members haven’t learned economics by now, they’re not going to learn it from your three minute testimony.

For all the mean things people sometimes say about developers, a lot of folks seem to fashion themselves amateur land developers, with a keen eye on exactly what types of businesses will succeed or fail. As it turns out, those things coincide perfectly with the things they personally enjoy.

That entitles you to one vote, just like everybody else. Now tell us what you came up here to say.

That entitles you to one vote, just like everybody else. Now tell us what you came up here to say.

Respecting people for volunteering time making plans doesn’t mean those plans should never change. Now tell us your reasons for or against this particular change.

Respecting people for volunteering time making plans doesn’t mean those plans should never change. Now tell us your reasons for or against this particular change.

Different people have different needs and desires! Just because you don’t like a particular thing doesn’t mean nobody would like it.

Yesterday, City Council voted to make it easier to build a backyard cottage (aka ADU, granny flat, garage apt, etc). Read the details at the Monitor. Here’s the lessons I took from the debate:

The granny flat resolution was introduced by Greg Casar, whose main claim to fame before City Council was as a labor rights activist. It was supported by the Republicans on City Council: Zimmerman and Troxclair, as well as Sheri Gallo (who has previously run as a Republican) [edit: I previously listed CM Gallo as a Republican, but now I’m not so sure] and three other Democrats: Adler, Rentería, and Garza. The four democrats who supported are definitely not “conservative” democrats in any meaningful sense. To understand land use politics, it’s best to set aside party labels.

This granny flat resolution was backed by urbanist organization AURA. It was originally introduced by urbanist Council Member Chris Riley. And it was seen past the finish line by CM Greg Casar.

But CM Casar didn’t come to the Council on a land use campaign with platform planks about zoning or parking restrictions; he was elected to Council on a platform of social justice and equity. Increasingly, though, he and other Council Members have seen many urbanist policies as boons for social justice.

This Council has not always been easy to predict. But this granny flat resolution was the second highly-contested land use case that took a long time to negotiate, but ended up in the same 7-4 vote. The interesting question to come is whether this group of 7 will start to see itself as a bloc and introduce more pro-housing ordinances, knowing that they probably have the votes to pass them.

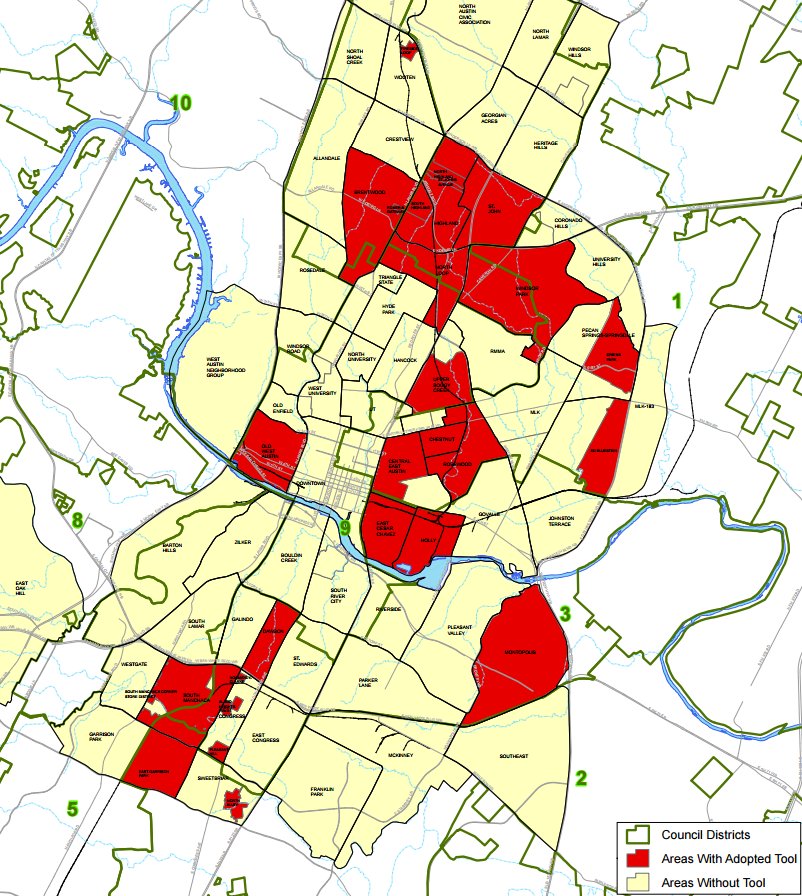

One of the major objections to this plan from CM Kitchen was that, by passing new ordinances, City Council was usurping the role of neighborhood planning teams. This was frequently an effective tact in the previous Council, where all 7 Council Members were elected at large and all feared alienating the politically active planning team members.

But while neighborhood plans were of clear importance to CM Kitchen and MPT Tovo, many of the Council Members in the new council pushed back, seeing neighborhood plans as an exclusive tool of the central city, not available to many areas further from downtown or to those who have busy lives and can’t participate.

Minimum parking regulations are one of the hardest, most expensive pieces of building homes, especially smaller, more affordable homes. Yet, they are also politically hard to change, in part because most adults in the city drive.

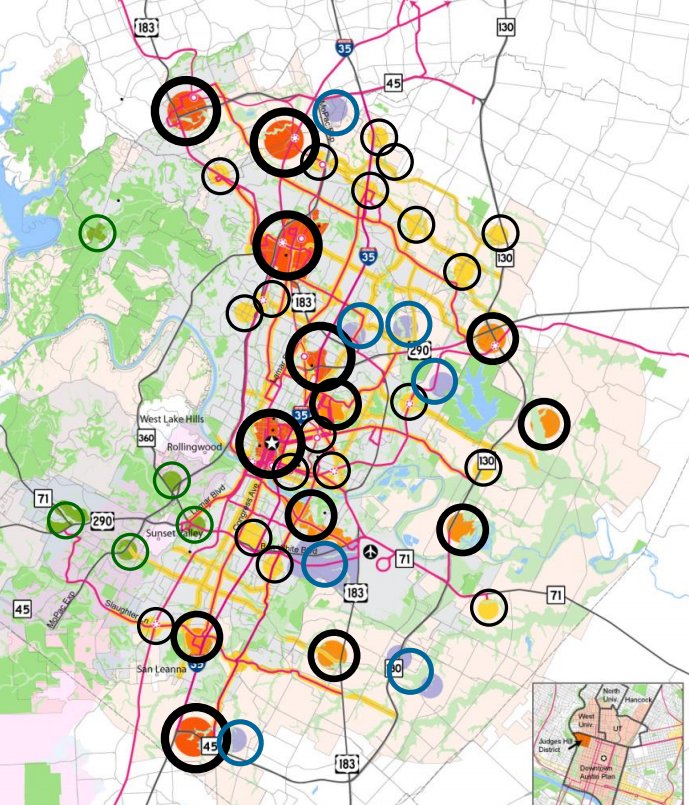

To solve this chicken-and-egg problem, the Imagine Austin plan envisioned activity corridors, along which there would be better transit service. In this resolution, Council made use of those planning corridors by reducing parking requirements along them. This may point the way toward more parking requirement reductions for other types of housing near these corridors.

The Austin Convention Center is considering expanding to another 3 blocks downtown. Here’s 6 reasons to be skeptical:

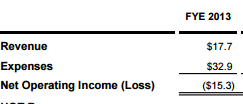

Even though the convention center doesn’t pay rent like a normal business, it loses stacks and stacks of money: $15.3m in 2013. It takes skills to run a business well enough to pay downtown rents. It takes special skills to run a rent-free business downtown and lose twice as much money as you make!

Even though the convention center doesn’t pay rent like a normal business, it loses stacks and stacks of money: $15.3m in 2013. It takes skills to run a business well enough to pay downtown rents. It takes special skills to run a rent-free business downtown and lose twice as much money as you make!

The only way the Convention Center can balance its budget is to take the lion’s share of the city’s $9 tax on every $100 that every single tourist spends on hotels in Austin–whether they’re in the very small minority here for a convention or the vast majority here to listen to music, visit family, do business, go to Lake Austin, watch a UT game, or any other reason! A case can certainly be made that we should tax visitors to pay for things many visitors want but don’t make much money–parks, music, arts, museums. But we spend the vast majority of our tourist taxes on just one thing–the convention center.

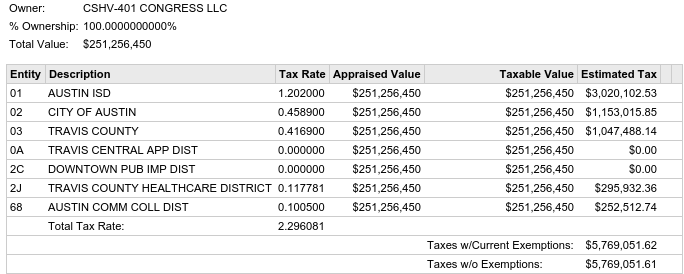

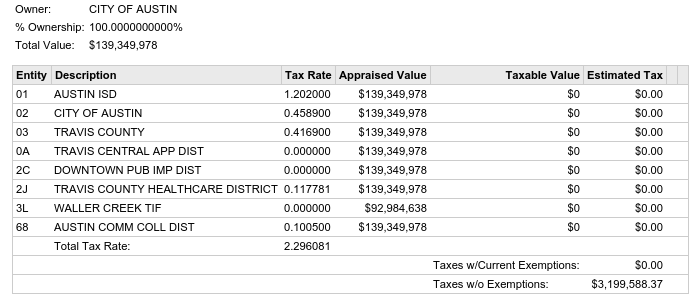

Unlike the Convention Center, most downtown buildings pay huge sums on property taxes:

If the Convention Center takes even more blocks off of the tax rolls, that could pull millions more dollars in potential taxes away from the city, the county, and Austin schools. That’s a property tax break EVERY SINGLE YEAR that we will be using to subsidize the convention industry.

If the Convention Center takes even more blocks off of the tax rolls, that could pull millions more dollars in potential taxes away from the city, the county, and Austin schools. That’s a property tax break EVERY SINGLE YEAR that we will be using to subsidize the convention industry.

When people come to conventions, they spend money at hotels, bars, and restaurants. That’s good–it puts people to work and generates tax dollars. But downtown condo dwellers and office workers not only spend money on lunch and cocktails, they also spend money on legal services and dentists and furniture and everything else, not to mention taxes that pay for schools and streets and parks. Is the economic activity generated by conventions more than that generated by other uses? Enough more to justify giving tax incentives? Do we lose any non-convention tourism business because of the costs of our hotel taxes? Are there better uses for our tourist taxes than more convention center? The analysis doesn’t even ask these questions, let alone try to answer them. C’mon guys! You’re asking City Council and taxpayers to invest $400m in a money-losing business and your business case doesn’t answer the most basic questions.

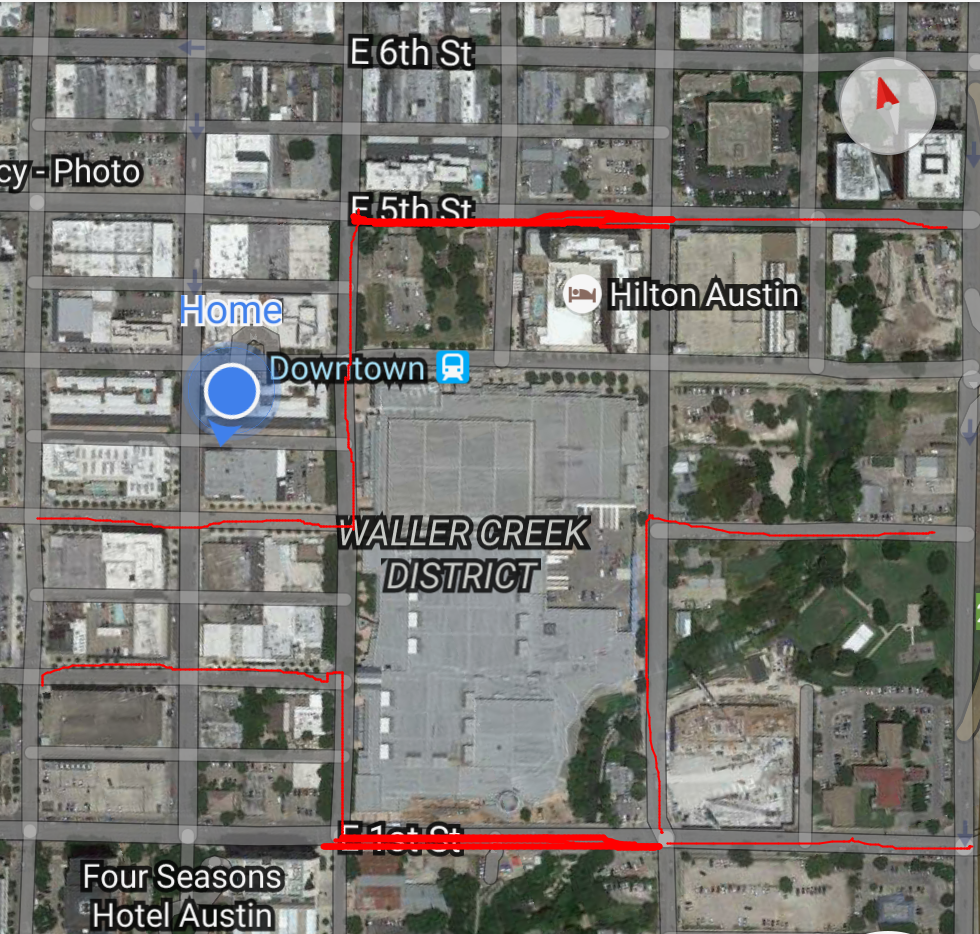

Most buildings downtown are pretty small and reserve their disruptive traffic (trash collection, loading/unloading) for alleys. Some buildings, like the W or the JW Marriott, take up a full city block, which forces disruptive traffic into the street itself. The Convention Center one-ups even these buildings by shutting down 7 combined blocks of 2nd St, 3rd St, and Neches, forcing all nearby traffic onto crowded streets like Cesar Chavez, 4th, 5th, Trinity, and Red River. Like channelized water with nowhere else to go, traffic on Cesar Chavez regularly floods. The new plan mostly envisions keeping Trinity open; it needs to go much further to keep all existing streets open.

Most developers downtown don’t just make a nice new building, they spruce up the area around them a bit too. The Independent condo tower is extending out the Shoal Creek Trail and building a pedestrian bridge. The 70 Rainey apartments are fixing up a park on the lot next door to them and building a wall covered in plants so neighbors have something pleasant to look at. The Convention Center has built one of the ugliest walls in all of downtown, helping to make Palm Park one of the most unloved and forgotten parks in the city. They say they’ve learned their lesson and they want to make the expanded section better. It would be a lot easier to believe them if they cleaned up their act first and put some real money toward fixing up Waller Creek and Palm Park and maybe trying to figure out some way to undo the ugliness of their current building. (Full disclosure: I’m affiliated with the awesome Generation Waller, but I’m speaking for myself.)

Really, not as much as this article makes it seem. But if the convention center authority wants us to believe their goal is improving the city, not securing their budget, they need to seriously step it up:

When the convention center was expanded in 2002, the world was a very different place. Downtown was filled with many low-value, low-intensity uses like surface parking lots and auto lots. One more low-slung ugly building fit in just fine. But now, the city is not approaching the convention center hat in hand desperately looking for jobs and downtown activity. The alternative to a convention center expansion isn’t a dead downtown; it’s a downtown Austin that continues to be one of the most prosperous, livable, desirable places to be in the entire state of Texas, radiating tax dollars out to fund the city. The Convention Center needs to understand this and improve their offer.

In addition, the days when the public was happy to give tax incentives to big businesses to get new jobs are over. Unemployment is scraping bottom in the city of Austin and City Council is rejecting hotel jobs (like the East Cesar Chavez hotel) even when they aren’t subsidized. Multiple bonds for 9-figure public projects like this one have been rejected by the public, for better or worse. An expansion plan that looks like a solid business plan for a money-making business will look an awful lot better to the incentives-wary Council members and public than red ink forever on an ever-growing budget.

The Texas Facilities Commission has produced a radical new document [warning: HUGE], outlining the ways they want to completely overhaul our state capitol. Check out some of their new ideas:

The major theme of the 2014 Austin elections was affordability and a major theme of City Council since then has been defining the word. Long-time readers of this blog are no stranger to tussles over the definition. Michael King took on the subject in the Austin Chronicle, taking aim at the Statesman’s editorial board and their false equation of affordability with “low property taxes”. I agree with King’s take here; the “taxpayer advocate” advice to cut, cut, cut has all the wisdom of a business leader saving money by eliminating the sales or R&D departments. Public spending can obviously sometimes offer public benefit.

But the part of the back-and-forth between the Statesman and the Chronicle I find most interesting is the question of growth. The Statesman states plainly that Austin’s growth “is not paying for itself,” while King offers the case that “growth does pay.” I’m a little irked by the question: we build homes for new people because they need homes, not merely because we can benefit as a city. But I think we can shed more light by changing the question a bit to: “What growth pays for itself?”

CMs Garza and Zimmerman had a debate I blogged about which kind of development imposes more burdens on the city: downtown towers or suburban sprawl?

In order to answer the question, I’m going to break the costs down into three types: building hard infrastructure (streets, sidewalks, water pipes), staffing soft infrastructure (police, firefighters, parks staff), and costs (externalities) we impose on one another through proximity.

The details of these questions can get pretty complicated, but I think the broad sweep actually isn’t tremendously complicated. For the most part, infill development–putting new buildings in places where there are already a lot of them–imposes lower costs and brings higher benefits to existing residents, while greenfield sprawl–expanding the city outward by putting new buildings in places where there haven’t been many before–imposes higher costs and brings fewer benefits to existing residents.

To the extent that new buildings can make use of existing infrastructure without having to add anything new, this obviously costs the city less in the short and long term. If an old commercial building on Burnet gets replaced with a vertical mixed-use building that holds both a commercial shop and some apartments, the new combined building will benefit more people and pay more in taxes. If that can happen all while the new residents are using existing water and sewer lines, buses, electricity substations, etc., this is essentially free tax money to the city. If some of the new infrastructure needs to be replaced but some of it can be used intact, then we have a partial discount.

But even if all of the infrastructure needs an upgrade, it is still cheaper to provide it in the urban core. Replacing 10 miles of aging water pipes in order to handle new capacity (as happened in West Campus to accommodate the UNO boom) means that you have 10 new miles of water pipes to maintain. Adding 10 new miles of aging pipes to handle new greenfield sprawl means that you have 10 new miles and 10 old miles of water pipes to maintain.

The same is true for many of the city’s resources. Placing new families near existing parks means more kids get to play in the park. Placing new families far from existing parks means that for those kids to have the same opportunities, we will need to build and maintain more parks.

Soft infrastructure is less clear. Until recently, the Austin Police Department based its recommendations on a constant ratio of 2 officers per every 1,000 people in population. This would result in the same costs no matter where growth occurs. If we are to gain (or lose) from growth, we may have to research new policies that change as the profile of our city changes.

There are certainly costs associated with dense living: more people using the same roads can slow us down; more conflicts over uses of the same park means you may have to reserve the volleyball court in advance. In part, this is the flipside of better resource utilization: a park that only serves a few people will always be available when those people need it, but its costs are spread out over fewer people. The price of having the roads or parks to yourself is paying for more roads and parks.

But there are mitigating factors here. When buildings are close together, people don’t need to drive as far to get to their destinations, reducing the amount of traffic per person. On top of that, destinations that are closer together allow for more travel modes to become practical: walking, bicycling, taking the bus. This can set up a positive spiral: the more people who take the bus, the more frequent the bus can come, making the bus more practical for more people.

Even the analysis above is only cursory: except for those lucky enough to own the last house they’re ever going to buy, the major affordability issues we face are private, not public: mortgage payments or rent, not taxes. A measure to require all new buildings downtown have a pink granite facade to contextually match the Capitol would have enormous private costs but little direct effect on city expenditures.

But focusing in on the public costs, as the Statesman and Chronicle are doing here, we still need better questions than “should we grow?” We will grow as a city if our children want to live here, if friends from Dallas, Victoria, or Round Rock stick around after graduating UT or ACC, and if more folks like me who grew up in the Northeast decide they’re done with winter.

Similarly, the questions we have to ask ourselves about affordability are not simplistic ones about whether taxes go up or down. We can cut taxes and postpone spending for a short period–or redirect taxes in the short term from homeowners to renters and business owners, as this Council has opted for. But ultimately, if we build roads we need to maintain them. If we want a city that doesn’t have potholes, we need to pay for it.

To truly tackle affordability, we need to get beyond the short-term fiscal questions and move into the long-term structural questions about how the shape of the city affects the costs of building and maintaining it. The question is not: “Should we grow?” The question becomes: “How should we grow?” Should we grow together or should we grow apart?

I’m honored to have today’s guest post from friend-of-the-blog Boone Blocker. Boone is an active citizen in the transportation field, having served on the city’s Urban Transportation Commission and CapMetro’s Access Advisory Committee. Boone was Rider Zero for UberACCESS; he brings his user’s perspective on the new service that provides mobility for people with mobility challenges:

Around the world and in our own community of Austin, people with mobility challenges have been and continue to be left behind by the current antiquated taxi system. These rides are unreliable at best and exclusionary at worst. Under the model which exists today, drivers frequently break off from trips and paying customers are left stranded with no idea if their driver is actually coming or in what timeframe they might be arriving. As an answer to this very real problem, an innovative alternative to the old tired system recently arrived on the local scene: UberACCESS.

UberACCESS is a first of its kind, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, on-demand, fully wheelchair accessible service. Instantaneously upon successfully requesting the ride, the passenger is alerted with the driver’s name and picture and additionally the type, color and picture of the vehicle. The passenger is also provided with the driver’s contact information if they need to relay any trip information and can carefully monitor the pick-up vehicle’s block-by-block movement and ETA as it approaches the pick-up location.

UberACCESS is empowerment in the face of hopelessness. It provides freedom and independence from the tyranny of transportation on someone else’s terms. It allows everyone to fully participate in all facets of our vibrant culture. We all see the world from different points of view and when a broader cross-section of our community is represented, we are able to forge new ideas together to break through the malignant status quo.

As we travel together in this brave new world of transportation, the inclusion of innovative companies and an engaged citizenry are imperative. This free-thinking environment produces solutions to problems which once seemed impassible. It’s equally as vital to have a flexible regulatory framework provided by the City, which affords companies the space to create and the citizens a clear conduit to provide our feedback for the necessary on-the-ground refinement of the products. We find ourselves on the precipice of a long overdue transportation revolution and we must do our utmost to ensure it benefits us all, not just the entrenched few.

A very small percentage of Austinites are homeless. During the January 2015 count of homeless individuals in Austin, a total of 1,877 homeless residents of Austin were found, or roughly 0.2% — 1 in every 450 Austinites. Yet, homelessness is a problem with an extremely wide reach. The knock-on problems that come from our inability to end homelessness emanate out in so many ways it can be hard to even be aware of all them. These are just a small sample:

I like to pick out videos from city proceedings which people explain the philosophies behind their actions. District 4 Council Member Greg Casar took the occasion of an appeal of a Conditional Use Permit denial for the use of Springdale Farms as an event space to discuss what he sees as the broader causes and cures for gentrification in Austin. The video is from ATXN, clipped by friend-of-the-blog Tyler Markham. The transcript is from the City of Austin. I have added formatting and light editing for readability.

Mayor, briefly, I think that you lay out very well the conditional use permit issue. Let me take a step back. In my mind there’s two very glaring facts about this situation in this case. The first is what you described very well: there is the issue at hand about one specific property, one specific conditional use permit and parking requirements needed, the noise mitigation, what is a compatible use on this piece of commercial property in this one narrowly tailored case. If it was just about that, then I think it would very simply be just another one of the many cases we see in a rapidly urbanizing city where uses start knocking against one another as we grow both residentially and as our businesses grow.

But what’s also glaring to me is that there’s a second obvious fact that clearly many people in the community, whether they’re nearby neighbors or people concerned about what’s happening in our city. This case is about something much more than that to many in this room for many different reasons, but especially some of the folks that came and spoke today in opposition. It means something about the racial and class divides in our city, about displacement occurring in our city, the change that is bringing some benefits to our city, but causing other detrimental effects as well. And that is a serious part of this conversation and the feeling that some folks think this would not be approved were it in another part of town.

My vote will be based on the first obvious fact, will be based on the merits of the conditional use permit, which is why I will vote for this. But I feel like it’s incumbent on us to acknowledge the second piece of this and to understand. I believe a lot of the folks that came and spoke before us have very legitimate concerns about whether or not this is a space that they feel is truly for that community. I’ve spoken with lots of people on both sides of the issue that live in the nearby neighborhood but I think it’s important for supporters of the farm and the owners to acknowledge and take seriously the concern that folks have brought up about whether they really feel like this space is for them and a community asset. I recognize that there have been attempts to do so but it seems clear to me that there’s still work on that front to be done.

People have brought this up as a cause of gentrification. I don’t see it as much of a cause compared to the ruthless global real estate market and our failed urban planning principles and racist institutions that we still deal with every single day, but I think the folks that have brought this up as a symbol or as a symptom of that kind of gentrification do need to be listened to and should be listened to. I ask every single one of you whether you’re on one side of this issue or another to participate in the broader policy debate about investing in affordable housing, even if it’s going to cost all of us a little bit of money. About rewriting and redoing the way we do our planning so that it’s not just up to some neighborhoods to absorb change, that there should be no such thing as a gated community that does not change. To talk about smaller living spaces because whether you like it or not and whether you agree with me on this or not, I see a city with rising land prices and I say the only way we can get people to be able to stick around in the central city is to find ways for us to live smaller and to use more transit and to invest in different kinds of housing

Stick around for the budget session right after this because we have temporary employees here at the city that don’t have healthcare and aren’t protected by our living wage standards and it’s that kind of a conversation that we need to engage in and it is the kind of conversation that when we’re talking about mixes of uses and different kinds of spaces in other parts of town that you hold us accountable to being able to support those when the noise is contained and when the parking is required and all of the sorts of things that I think was hammered out in the hard-fought compromise that makes probably no one happy. So I call on my colleagues to take that issue seriously and I appreciate the conversation this has begun but it’s got to be about way more than one small zoning case.