Summary: To measure how much “shaping” a rail plan does, don’t look just at static 2030 projections.

In the latest Central Corridor Advisory Group meeting (video here), there was an interesting question of whether the most important numbers that Project Connect should use when evaluating potential rail routes are the data from 2010 or the CAMPO projections for 2030. Kyle Keahey, Urban Rail Lead for Project Connect, framed this decision as “serving” existing populations or “shaping” land use patterns and future growth.

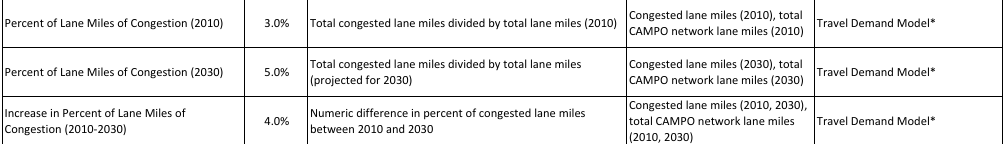

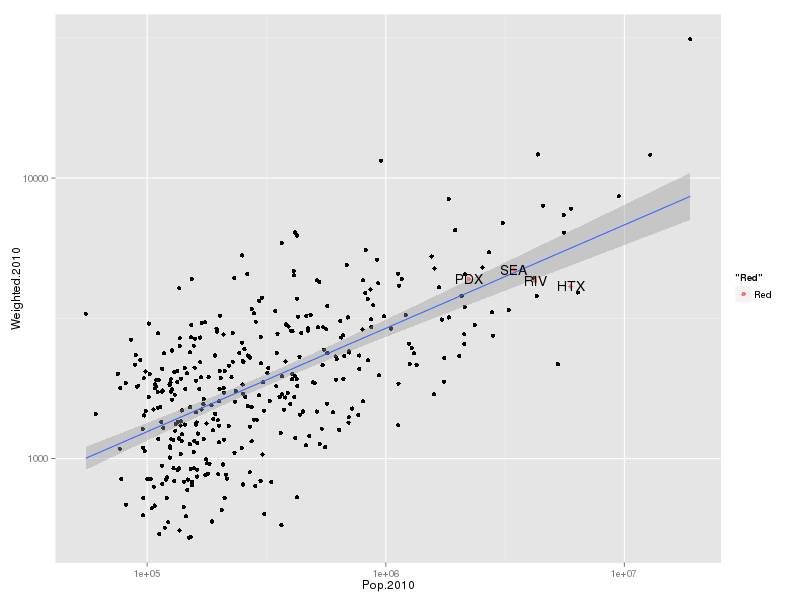

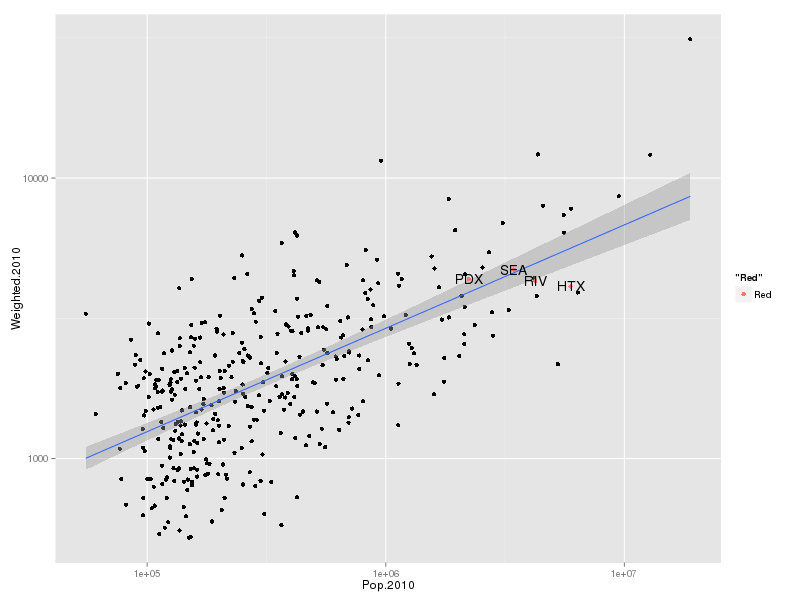

Serving and shaping are both valid but aims of a new rail plan, and each goal might be achieved to a different amount by different plans. However, the way to measure them is not the 2010 data vs. the 2030 projections. The 2030 projections are based on the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (CAMPO) model, which I do not believe included any provisions for rail. Therefore the growth it projects, according to the model, is coming even if we don’t build rail. Building toward that growth is still a mode of serving, just serving a future population, projected to exist even in a no-build scenario.

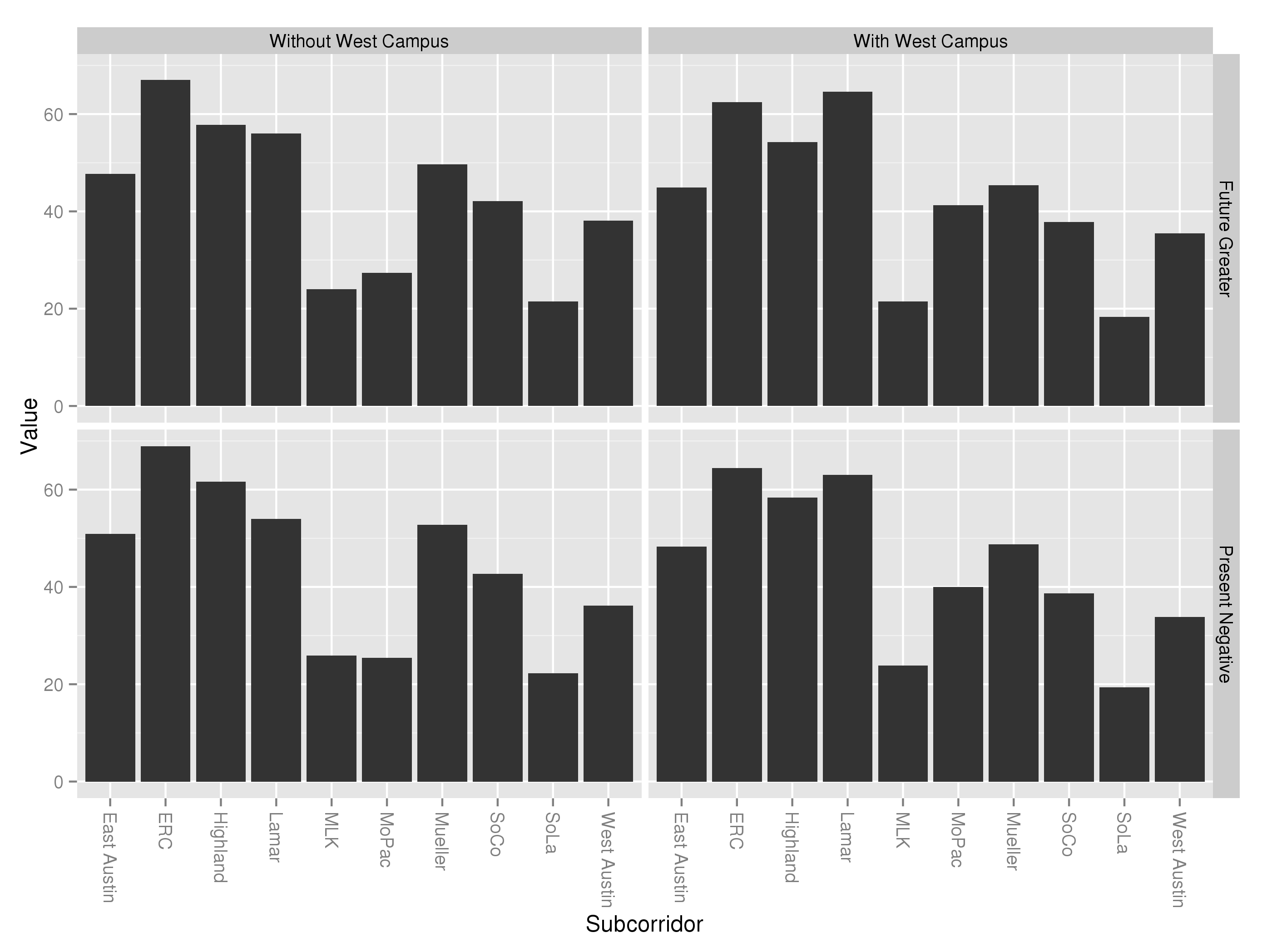

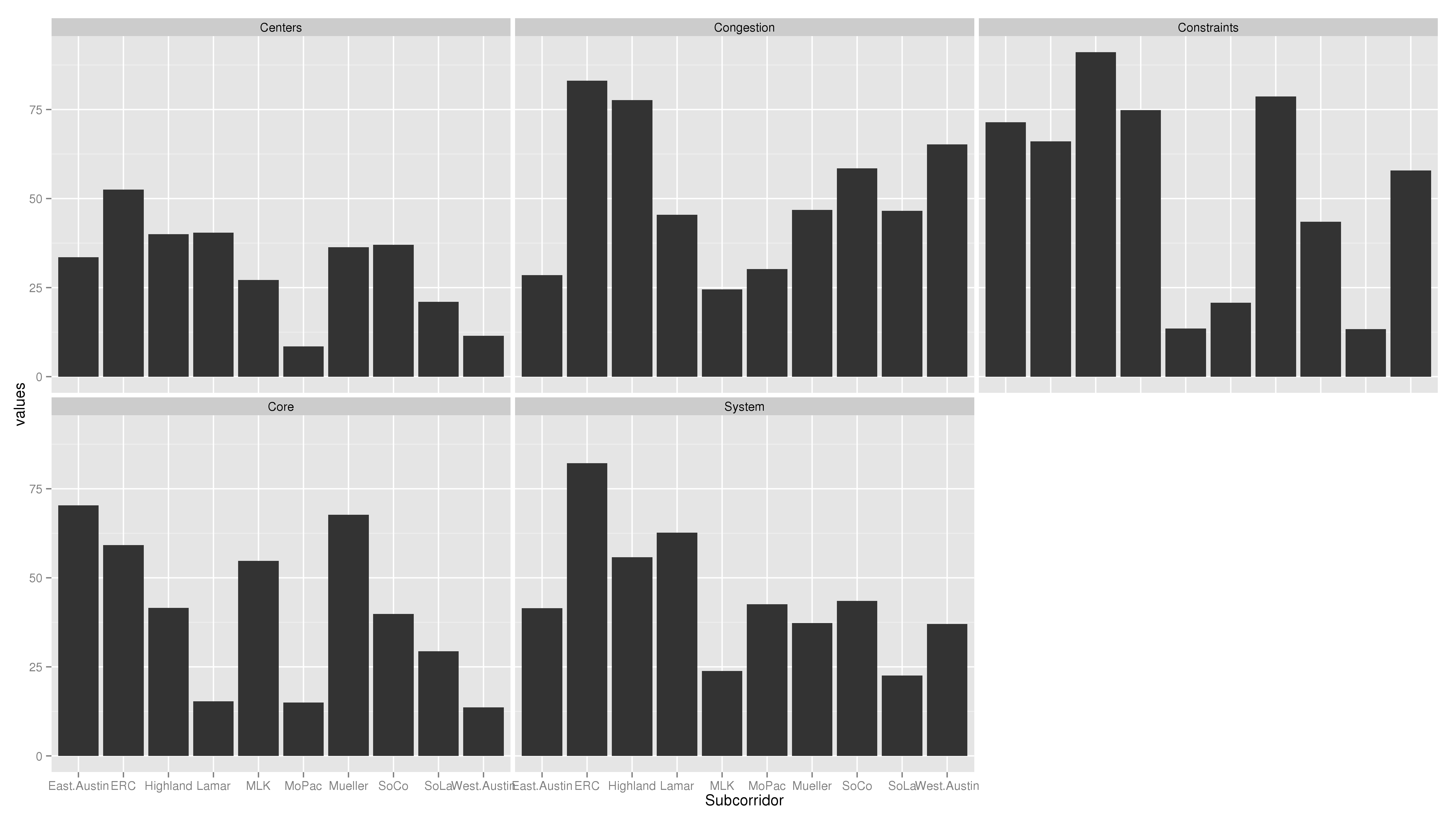

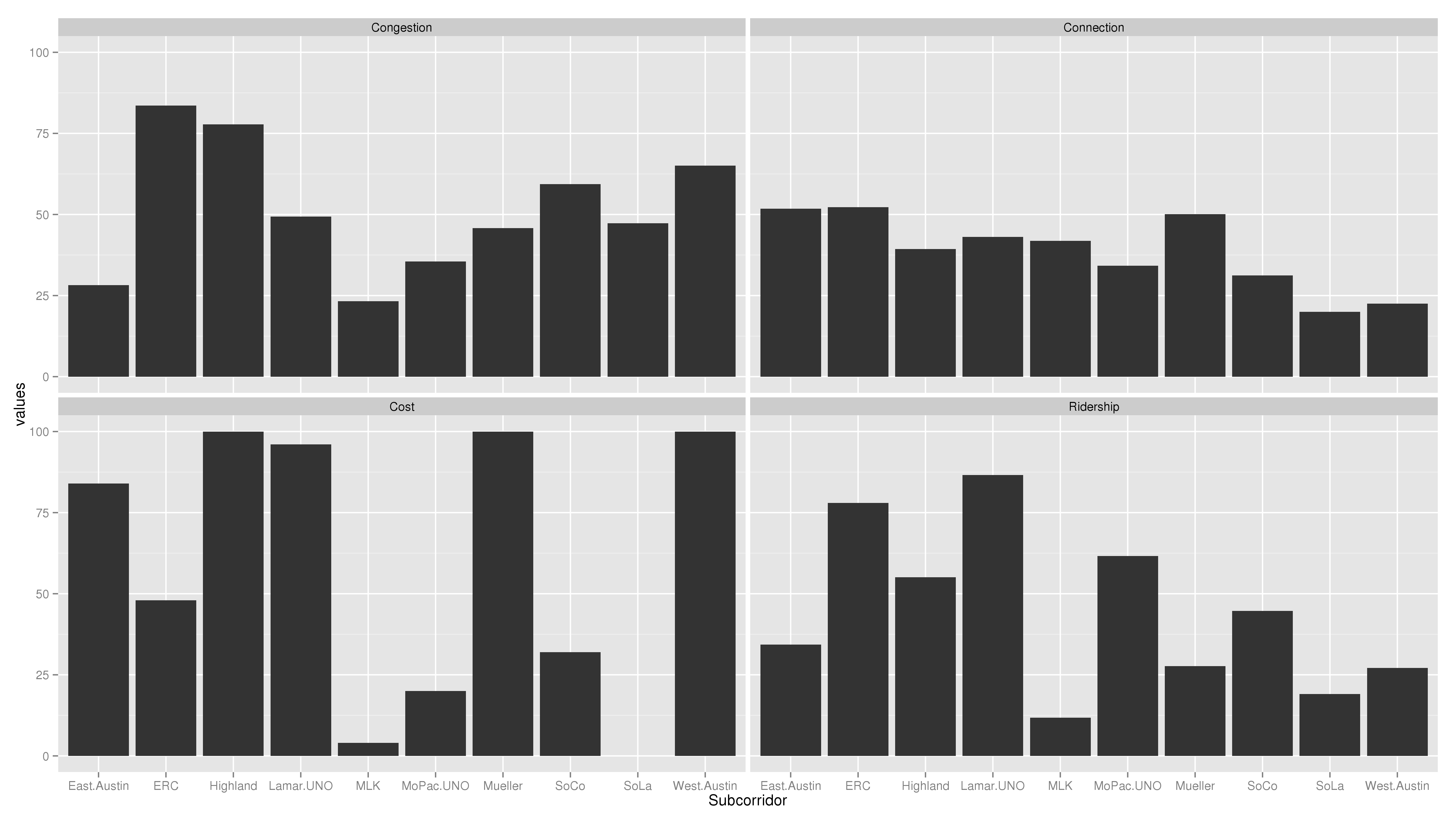

But these projections aren’t set in stone. Areas might grow faster or slower than assumed or even lose population. Sometimes, changes in projected growth can be for reasons that nobody anticipated: Seattle’s Eastside suburbs would probably never have grown so fast if it weren’t for the explosive growth companies like Microsoft experienced. But often, the changes in growth are due to policy decisions. West Campus, for example, experienced explosive growth when the UNO zoning plan came into existence, allowing growth to occur. The East Riverside Corridor plan that City Council passed is similarly all about shaping the nature of future growth along that corridor. The “CAMPO model” (PDF) doesn’t actually consist of one projection, but two: one based on a no-build scenario and one based on a “financially constrained” scenario. By comparing projections based on each transportation plan, CAMPO is analyzing how each plan shapes the future.

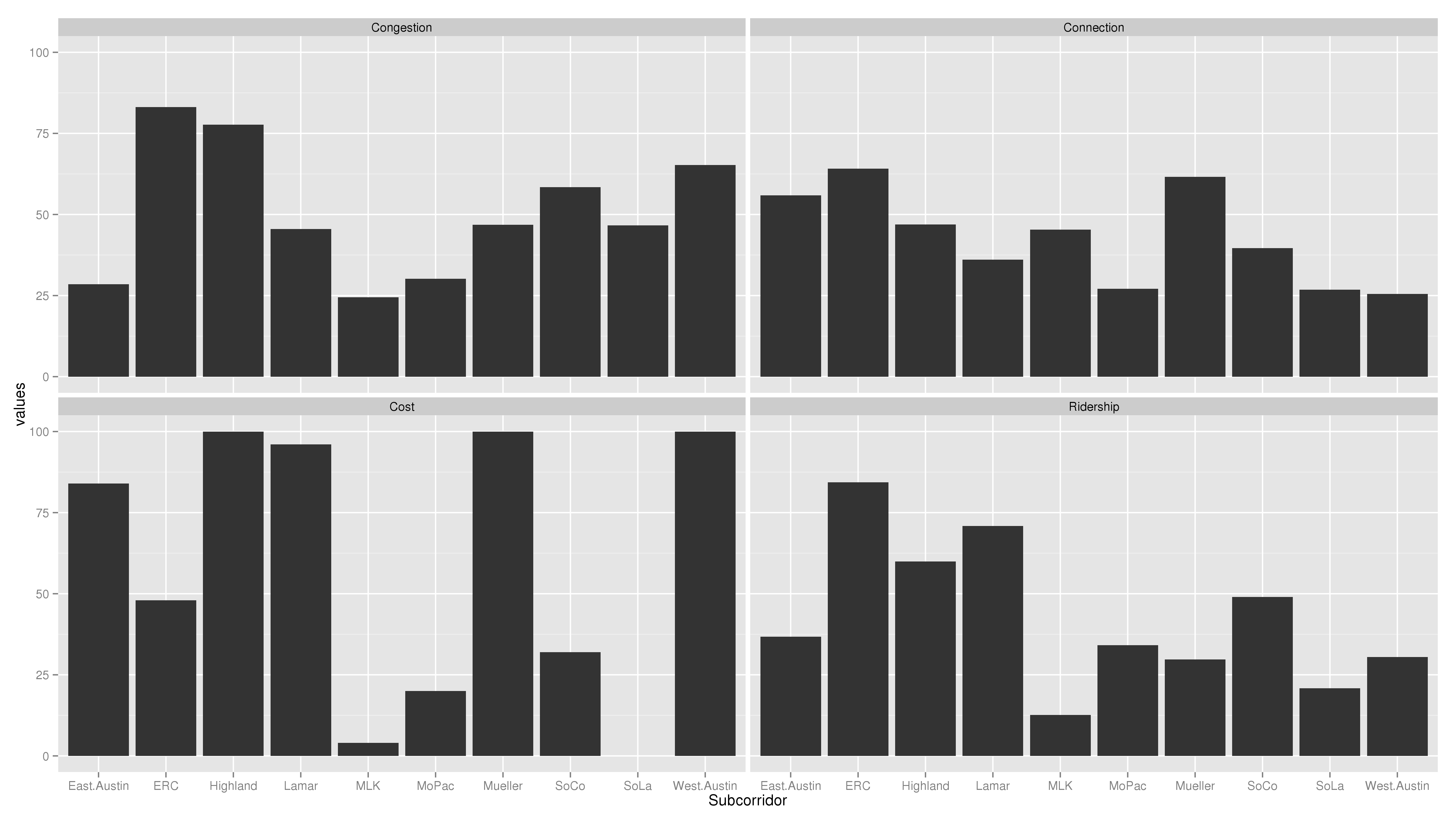

If the Central Corridor Advisory Group is being asked to shape the future and not merely serve, it will need similar alternative projections. There may not be time to perform as sophisticated an analysis as CAMPO does, but it at least needs to be aware what sorts of questions it’s trying to answer. Questions like: if we put rail here, will that result in more people living there? Working there? Living there without cars? The answers to these questions are difficult, but shying away from them or assuming answers because the questions are difficult is not a good way to make decisions.

After all, if we don’t believe that spending $500m on a rail system will change the projected future land use and transportation patterns of our city, we might as well save that money and not build it at all. I think rail is one foundation for shaping the city and that’s why we’re pursuing this process. But that means that, instead of merely chasing one static, no-rail projection of 2030, CCAG should be planning what 2030 will look like.

Rail alone can’t achieve that plan. If a neighborhood is as built out as zoning allows it to be, then frequent, high quality rail service will not draw new residents, merely raise property values and make the area less affordable. That is why I think it should be clear to residents that, if we are planning on building a rail line to your area, that will have to go hand-in-hand with reshaping your area to be amenable to rail, by including high-density zoning, high grid connectivity, and all the other elements that are necessary to make a rail line successful.

Edit: After I posted this, Jace Deloney took to twitter to make some excellent points about this post. Read the storified version here. One point he made was that we should look to serve places “that already have the sort of density & zoning that can support high transit service.” I agree! Sending rail to places where it is needed and that will make the best use of it is the right move! I just want to point out that if you are going to try to shape a place with rail, you should use at least use measurements of shaping that make sense, and not static projections.

The point I was trying to, but failed to make in the final paragraph was not that sending rail to already-built places is wrong–indeed sending rail to already-built places is the best guarantee that by the time you build it, there will be people there–but rather, that your future growth projections should be in line with land use law. If the law doesn’t allow for the kind of growth you are projecting, you are making projections not only about future consumer demand for living spaces, but also about what future City councils will pass. Perhaps that makes sense for a private-sector forecaster, but for the City Council itself to pass the plan, the Council should either go ahead and pass the law that allows for that growth or it should not use that growth in its projections.