For all of you reading this shortly after it’s been posted, no context is necessary. But in case anybody ever goes back and reads this months or years from now, here’s the situation as I write this. Most folks in Austin are working from home on account of the global pandemic COVID-19. Dining areas in bars and restaurants are closed. Yesterday, 18 positive tests for the virus in Austin were added to the 23 existing ones. 2020’s edition of SXSW was cancelled and a large chunk of SXSW, Inc’s workers were laid off. So many other workers are being laid off in Austin and around the country and world that people are starting to ask whether the economic collapse will look more like the Great Recession or the Great Depression. Cap Metro has reported a nearly 50% drop in ridership and has dropped service to mostly Sunday-levels. I could go on and on but suffice it to say the situation isn’t looking good.

Politics

West Campus Two Point Ohhhhh Yeahhhhh!

I may have written about West Campus a time or two before. But this time I come not to praise West Campus, but to bury it — in new developments! On Thursday, October 3, Austin’s City Council will consider the biggest changes to the rules that govern a good chunk of West Campus (known as UNO or the University Neighborhood Overlay) since they were initially passed in 2004. The proposed changes would:

Economic Development without Tax Breaks

Economic development incentive deals — tax breaks to companies for bringing jobs to a city — have had a pretty bad run of news in Austin and beyond. Amazon’s HQ2 headquarters search earned a mile of negative attention for every inch of excitement even before they gave up on a deal with New York.

In Austin, economic development deals have been controversial for a while.

A Christmas wishlist for Austin’s next City Council

Austin’s new city council is shaping up to be the most development-friendly Council in recent memory. What kind of agenda could we expect or hope to see from the new City Council? Here’s what’s on my holiday wishlist.

Reform before Rewrite

CodeNEXT is dead. One reason it failed is that it combined two separate but related goals: increasing density and improving design. How dense different parts of Austin should be is a subject of intense debate. By contrast, the best ways to design Austin given a certain level of density is debated mostly by professionals. To the extent that the public debated design elements at all, the arguments sounded an awful lot like the only thing most people cared about is how these design elements affect yield. Looked at it this way, CodeNEXT was doomed to fail. It’s impossible to write coherent design guidelines when the public takes intense interest in them but evaluates them solely based on how much housing (or other buildings) they produce.

We must at least try to separate the issues of density and design. Improving the presentation of the code, the process of getting building permits, improving our streetscapes; all important issues that need a collaborative process informed by technical know-how. On the other hand, the question of whether we build a city that sprawls outward or soars upward is one with a lot of public input from the kinds of people who vote in municipal elections. It’s a question that has divided the electorate to the point of dividing communities like environmental groups and neighborhood associations. This is not an issue we can hope to just keep talking about until we find common principles. We don’t need to be nasty in how we debate the issue but we need to recognize that dumping these political questions on to staff and community engagement is doing more to cause rifts than heal them, without providing meaningful benefit. So, for my Christmas wishlist, I hope that our City Council takes a bold leap of faith and does the job they were elected to: settle political issues. That means making real movements on density even without the comfort of a completely undivided city. My real wish here is that come next Christmas, Austin can stop debating whether we are a place that welcomes new residents and start moving on to debating how we welcome new residents.

How could we do that? Here are some ideas:

Build up commercial streets

Austin has seen a number of new apartments (usually built on top of new shops or restaurants) on commercial streets like Burnet, Lamar (North and South), and South Congress since it first started allowing such buildings in 2004. They’re not my personal favorite housing style; I prefer to live on side streets with less traffic noise and pollution. But there’s no doubt that they’ve been a very popular type of new housing. They produce new homes for a lot of people who need them and they’re very easy to serve by transit, as streets with shops are already our most common bus routes. The new buildings are required to follow design guidelines that make the city more walkable, by doing things like limiting the number of driveways that interrupt sidewalks.

Here are three items on my wishlist to build on the VMU program’s success:

- Allow apartments on more streets. If a bus goes there, it should allow VMU.

- Allow apartments on all parcels on a street. Austin’s VMU ordinance made a political deal where it agreed to limit the program to certain parcels, which well-informed members of the public willing to sit through long meetings got to decide on. But that was 10 years and $1000/month in rent increases ago. It’s time to fill in the missing teeth and allow more properties to rebuild.

- Apply it to “Centers” as well as “Corridors.” This was an idea from the city of Austin comprehensive plan “Imagine Austin” that envisions a few more neighborhoods not dissimilar to West Campus with fewer undergraduates or Seattle’s Ballard (click through on the tweet to see the whole walking tour):

Self-guided walking tour of Ballard, one of Seattle's urban villages. Here's a conventional grocery store tucked under apartments, wrapped around parking. pic.twitter.com/dKEcyG6Acg

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) September 4, 2018

Allow more missing middle housing

“Missing middle” is the idea that there’s not a lot of ways to live in Austin that fall between a house surrounded by yard on all sides and an apartment complex with a leasing center with little bowls of candy in the waiting room. In other cities, you get lots of housing types in between: triple-deckers in Boston, greystones with up to 6 apartments in Chicago, or row houses in virtually every city the entire world over. Missing middle housing types can be employed on busy commercial streets; many cities have rowhouses interspersed with shops. But it really shines as a way of allowing more people to live on the calmer, quieter side streets where adults and children both are safer walking.

Redesigning Austin around missing middle housing is going to take a lot of work. We have effectively destroyed so much of our missing middle heritage that Austin’s Historic Preservation Officer proposed landmarking a fourplex as a rare example of a bygone housing type. But there are some items on my Christmas wishlist that are ready to ship today:

- Remove restrictions on subdividing buildings. If you’re allowed to build a mansion for one family to live in, you should be allowed to build that same mansion split into multiple apartments. This wouldn’t affect the health and safety regulations, nor would it affect regulations that affect the form of a house. It would simply take advantage of the fact that many of our houses are built too large and could accommodate more people with an extra stove and a wall between two sides of the building.

- Reduce minimum lot sizes. Austin requires unusually large amounts of land, measured in both area and width, in order to build a house or apartment building. Austin’s oldest and most beloved neighborhoods were built before that rule and have many lots with housing on smaller lots. Requiring so much land was a mistake and we should drop it sharply.

- Treat missing middle like houses not mega-complexes. Austin has a different set of rules for getting permits to build houses versus getting permits to build large buildings. While both types of buildings are required to follow zoning rules, large ones have to go much further in proving that they’re following the rules. This doesn’t have a huge effect on mega-complexes, which are always going to require complex permitting. But the additional paperwork can make it simpler to build an upscale mansion than a simple fourplex.

End Parking Requirements

Requiring that every house, apartment, store, school, daycare, and bar have its own parking places is crazy stupid. It encourages people to get an extra car even if they could get by without it, it adds crazy large expenses to everything we build, and it makes the city ugly as heck. Once you realize how much of a city is built the way it is just to provide huge amounts of parking, you’ll feel like you’ve just put on the goggles from They Live:

Parking requirements aren’t one of those “we just disagree on the right amount” ideas. They’re always wrong and the best thing we can do is eliminate them entirely. But if that isn’t on the shelf at the mall, some good alternatives could be:

- Eliminate parking requirements near buses and trains.

- Eliminate parking requirements in special districts like TODs and West Campus.

Expand Downtown and West Campus

The downtown/UT campus area is a special place, different from any other part of Austin and in some ways any other part of Texas. Austin has one of the largest percentages of jobs in its central business district, understood in this case to extend all the way up to UT. Although this can cause problems with car traffic when many people commute in from around the city surrounded by their steel cages, it’s a huge advantage for running transit. These areas are both doing very well but threatening to run out of room as they get built up. So what would I love to get to fix this?

- Rezone more of downtown to CBD or DMU, the two zoning districts special to downtown.

- Expand West Campus’ special zoning to more parts of West Campus.

- Expand the “inner West Campus” zoning district that allows taller buildings to more of West Campus.

Start working on Comprehensive Zoning

Design and density go best together. A comprehensive rewrite of our land development code could be far easier to achieve once the Council has set the policy direction clearly. But no matter what, it’s going to be a long process. When CodeNEXT died, many people from within the development and homebuilding industries actually let out a sigh of relief as they felt many of the areas outside the public interest weren’t well-enough examined. Outside of the pressure cooker of setting the city’s direction on density, real progress can be made on the more technical aspects of the code. Let’s start.

Election reflection: three big changes that have affected the makeup of Austin City Council

With the completion of the runoffs, Austin’s next City Council is set. Although it falls short of the densificatron the Austin Chronicle mused about, it is being widely hailed as the most urbanist-friendly council in recent memory. How did we get here? Well, I’d like to believe it’s because the world is coming to understand that building awesome, compact cities is the only way for humans to prevent catastrophic global climate change. In fact, I do believe that. But there’s also some structural, political reasons. Let’s listicle.

1) Higher turn-out elections

It’s no secret low-turnout elections favor Republicans and development skeptics. In 2016, development-friendly candidate Sheri Gallo led development-skeptic Alison Alter on election day 17,569 to 12,943, coming within just 634 votes of winning the 50% needed to avoid a runoff. But by the time the low-turnout December election came around, Alter won out 9,481 to 5,339. It’s possible there were some voters who changed their minds but more likely development-skeptic voters were just more motivated to turn out in December. Development-skeptic candidate Laura Morrison said her strategy was to force a runoff, where the smaller, more development-skeptical electorate would favor her.

Showing up to vote for the runoff at the same location where you early voted and finding this sucks a little bit. pic.twitter.com/H7rZfcGf2k

— David Whitworth (@dcwatx) December 11, 2018

But while our two-part runoff system means we have some low-turnout ballots, it used to be much worse. Prior to 2014, we elected City Council in May elections rather than November ones. The transition to higher turnout elections has brought out a broader group of voters with a broader set of issues, less animated by opposition to development. This trend could accelerate if Texas, like Maine, adopted instant runoffs, in which voters state their second (and third and fourth, etc) choices at the same time they select their first choice, allowing a runoff without forcing voters to come out twice. However, Ed Espinoza on Twitter tells me it may take a change to state law in order for this to happen:

It was an opinion by then-Secretary of State Henry Cuellar.

— Ed Espinoza (@EdEspinoza) December 13, 2018

2) 10-1 gave more representation to underrepresented populations open to development

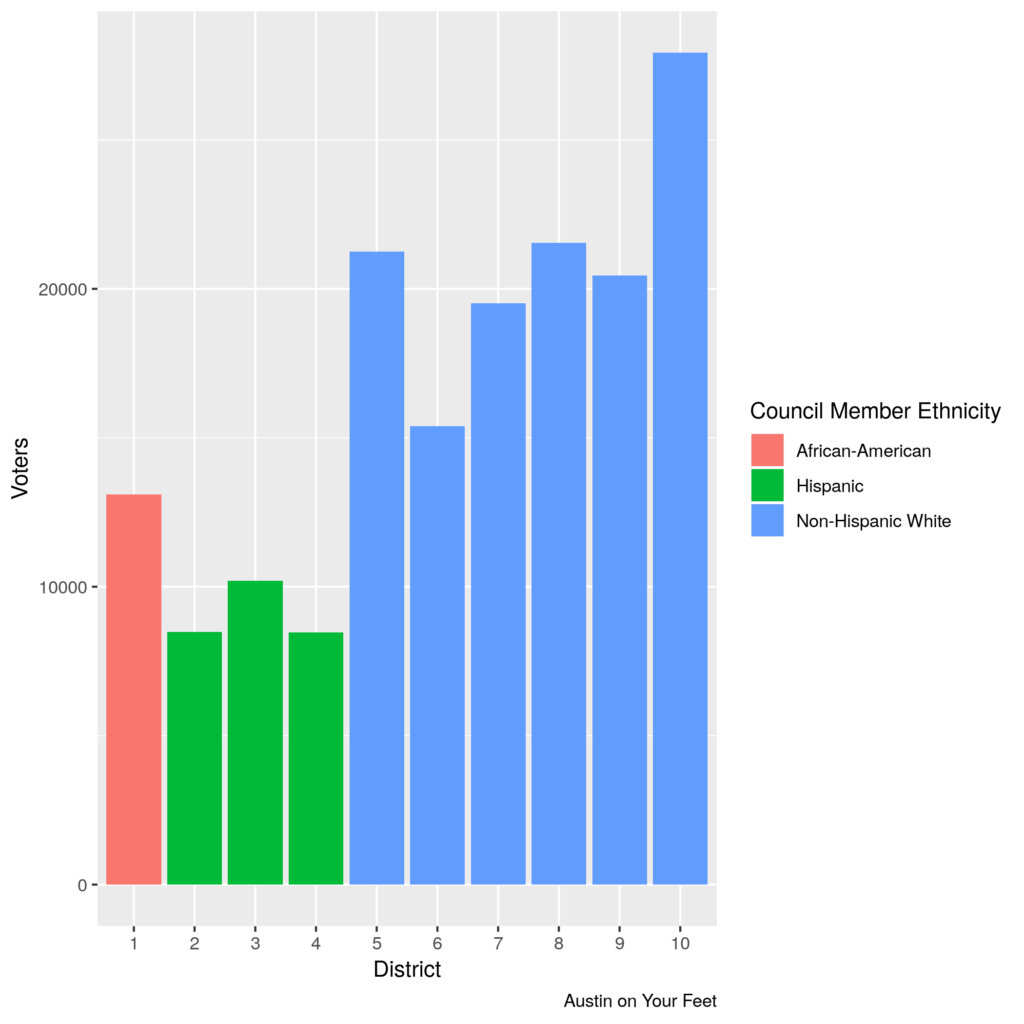

Both before and after Austin switched from seven at-large Council Members to ten single-member districts and one at-large mayor, the vast majority of votes in Austin have come from the richer, whiter parts of town. Here, for example, are the total number of voters in each district in the 2014 city council elections, as well as the racial / ethnic group of the Council Members who have represented that district:

All districts were made to have roughly equal numbers of people living in them. But not all of those people vote! There were more than three times as many votes cast in 2014 in wealthier, whiter District ten than in poorer, more Hispanic Districts two and four. This difference is driven both by the number of eligible voters and by voter participation rates. When all Council Members were elected at large, this meant that the votes of the areas and populations that turn out at lower numbers were diluted among the votes of the areas that turn out at higher numbers. Since 10-1, these areas are represented at a proportion to their populations, not to their voting rates.

Of course, it isn’t a given that “population that votes in great numbers” or “white” are anti-development or “population that votes in lower numbers” or “non-white” are pro-development. Ora Houston of District 1 was a consistent development skeptic, while Jimmy Flannigan of District 6 and Sheri Gallo of District 10 have been more development-friendly. But generally, the electeds and the electorate in the less white districts have proven to be more open to development than the whiter, more voter-rich districts–and this is true in other places outside Austin as well. Indeed, if you look at the five districts with the fewest votes in the 2014 election (one, two, three, four, and six), these districts will be represented by some of the most development-friendly Council Members on Council in 2019.

3) 10-1 created new, geographically based sources of legitimacy

Prior to the 2014 switch to a district-based council, all Council Members were elected by an electorate from across the entire city. When we were considering the switch from at-large Council Members to geographical districts, there was something of a debate on what was likely to happen between two of my friends and fellow bloggers, Chris Bradford of Austin Contrarian, who feared that this would create a system of ward privilege, and Julio Gonzalez of Keep Austin Wonky, who was a bit more sanguine. At the time, I leaned closer to Chris’ argument but so far, Julio’s predictions have turned out to be more accurate. On issues that affect a single council district, Council Members definitely defer to the district Council Member in some ways; often, the Council member whose district is most affected will speak first and longest on a case. On cases where other Council Members don’t have developed opinions, they may choose to vote with the district Council Member. But Council Members have also shown a lot of willingness to vote their consciences.

Indeed, there’s a sense in which geographical districts have actually reduced ward privilege. When the Council was elected at large, they often gave a significant amount of deference on zoning cases to leaders of the nearest neighborhood associations. While neighborhood associations are unelected, they were still often seen as a good pulse of what voters thought in that district. Now, with single-member districts, some neighborhood associations still have a large amount of sway where voters elected a Council Member that agrees with them. But in other Council districts, anti-development forces have had to handle a diminution of their authority as they put their preferred candidates to the electoral test and lost.

Nowhere has this been clearer than District 3, where Pio Renteria has won two straight elections over his sister Susana Almanza. The siblings have been on opposite sides of neighborhood politics for decades; Council Members trying to get the pulse of East Austin sentiment sometimes used extremely imperfect proxies like how many people showed up to debate an issue at City Council. Now, with voters choosing Renteria twice, there is little reason for other Council Members to value Almanza’s voice over Renteria’s.

Where from here?

Politics has a way of going through pendulum swings. It’s possible that norms of ward privilege will emerge over the course of years. It’s possible that I’m overreading the factors above and luck has played a large role in the formation of the Council. After all, the same District 1 that elected development-friendly Natasha Harper-Madison also elected development-skeptic Ora Houston. But it’s also possible that these changes in Austin’s electoral system have led to a real structural shift in politics that could have big implications as Austin becomes closer to a big city.

Opportunity Kicks

The hottest political topic in Austin right now is a proposal by the owner of the Major League Soccer franchise Columbus Crew to lease space on a city-owned parcel in North Austin. To see the more colorful side of the debate, browse the #MLS2ATX or #SavetheCrew hashtags on twitter:

Just a regular #CrewSC tailgate. #SaveTheCrew pic.twitter.com/JcGJHv6Vld

— David Miller (@DavidMiller0789) August 11, 2018

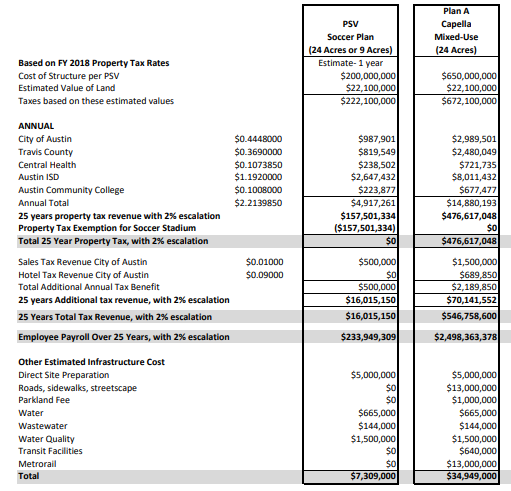

I’m not going to rehash the debate, but rather pick out one piece of the “no” side’s argument, led most strongly by CM Leslie Pool: the opportunity cost of leasing the parcel for a stadium. While the lease would be a financial positive for the city compared to doing nothing on the land, that isn’t the only other option. A nearby property owner/developer, for example, has proposed an alternative plan where they buy the land, build a relatively dense mixed-use development, and pay taxes annually estimated at $15m per year. The “opportunity cost” argument is a really good argument. In fact, this argument is so good that I’ve made it a few times myself over things like the immense value to the city of new construction in West Campus, or the potential opportunity cost of a tax-free convention center annex. (Proud that the proposal I successfully passed in the Visitor Impact Task Force recommended a future convention center annex remain taxable.) In fact, this is such a great argument that I desperately, desperately wish people used it more often. In a previous policy decision, the decision on what a Planned Unit Development agreement would look like for “the Grove,” a plot of land off 45th Street near Mopac, one of the leading opponents of a similar sort of dense mixed-use development was the very same CM Pool and I don’t recall her carefully weighing the benefits of limiting residences there against the tax revenue the city would forego by allowing more construction.

But the point isn’t to discredit the argument by calling hypocrisy. The argument is really good! It’s an argument worth making! While large developments like the Convention Center annex, McKalla Place, or the Grove are relatively visible because they’re covered in local media and debated by City Council, virtually every land use decision that the city makes has a fiscal dimension, yet we rarely ever think about it. (To his credit, Council Member Flannigan frequently invokes the fiscal impacts of development patterns.)

So, let’s talk about fiscal impacts!

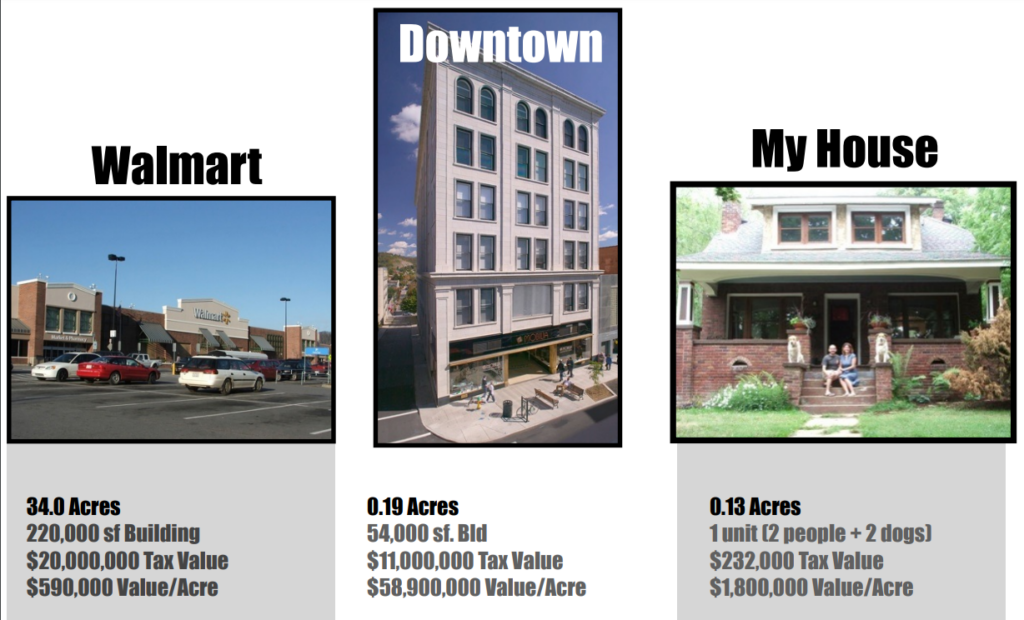

Rule 1: Compact development tends to be more valuable

In a fantastic presentation prepared for the Downtown Austin Alliance, consultant Joe Minicozzi compared the fiscal returns to a city from different kinds of development:

While a Walmart may have eye-popping tax values because it’s such a large single development compared to a traditional low-rise office building or house, a low-rise office building also requires much less space to deliver value. Many of a city’s costs, like building streets, scale by the linear mile not by the person. It costs much much more for a city to provide services to a Walmart than to a downtown city block. For residential buildings, the same rules apply. If a city has 5,000 residents, it’s easier to provide them services if they live in a single cluster of 250 acres than if they spread out to 4,000 acres. In Austin, we see these expenses in items like the five fire stations the fire department has requested to cut down response times on the outskirts of the city. I don’t begrudge people who live on the outskirts fire stations. But I do wish we had denser land development patterns in the central city to better take advantage of our existing fire stations and roads.

Rule 2: Value is driven by making great places for the long term

Take a look at the Capella proposal again. In addition to the $15m in annual tax revenues, they will pay other costs: for example, $1m in parkland dedication fees. Additionally, they have offered $22m for the purchase of the land. These types of one-time fees, both voluntary and required, typically dominate policy discussions but they are drops in the bucket compared to the long-term tax revenue from building a great place that could last a century or longer. The financial life-blood of a city is not in one-time fees but recurring taxes levied every year on great places for its residents to live, work, and enjoy themselves.

When a city considers the fiscal impact of a development, the question it should be asking itself is not how much can we extract from this developer today but: is this developer making a place that 50 years from now people will still want to be in and still be willing to pay taxes on? The Littlefield and Scarbrough Buildings, two modest 8-story downtown Austin office buildings that were anything but modest at construction time pay close to $1.4m in taxes year-in and year-out more than 100 years after they were built, after their historic building tax breaks!

Rule 3: Taxes are only one of many benefits to consider

Of course, not all of life can be boiled down to profit and loss, tax revenues and maintenance costs. Parks cost taxes to maintain and don’t directly raise taxes themselves, yet most of us love them. Comparing the often difficult-to-quantify benefits with the easy-to-quantify costs can be difficult and frustrating, as both CM Pool and CM Flannigan express here:

👀 #atxcouncil pic.twitter.com/tb91veWJZO

— Nina Hernandez (@neenthirteen) August 11, 2018

There’s no obvious right decision on a given question. Is it worth it to Austin to pay millions of dollars in maintenance and forego even more than that in taxes for things like the Butler Hike and Bike Trail, Zilker Park, or Barton Springs? The overwhelming majority of Austinites would say yes. Is it worth it to Austin to forego millions of dollars in taxes to “bring people together” through a soccer stadium or to prevent dense development on the former TxDOT site? Could it be worth it to create another West Campus, throwing off tens of millions in tax revenue annually to fund things like parks and schools and soccer fields? Austinites are much more split on these questions and that’s why they’re political decisions. But if we want to make good choices, we need to understand the costs and benefits clearly.

Can CapMetro CEO Randy Clarke hit the Project Connect softball out of the park?

Project Connect, the government group responsible for proposing big ideas for the future of Austin transit, has unveiled their latest vision (shown below). I haven’t dug into the details as much as I will over the coming months but from 10,000 feet, I’m impressed. Their analysis confirms that water is wet, the sky is blue, and the three corridors where light rail makes sense are Guadalupe/Lamar, East Riverside, and South Congress, with Guadalupe/Lamar being the very best. Additionally, the analysis identifies two more high-quality transit routes (South Lamar and Manor) where great bus service could work well and one medium-quality transit route (ACC Highland via UT campus and Red River) where pretty darn good bus service is possible. There’s also an interesting thought for a future connection to the Domain.

Although I haven’t done an extensive survey of transit advocates in Austin, most of the talk I’ve seen about this plan has been extremely psyched. This isn’t just one expensive but low-ridership rail route for the point of having rail, but a system of interlocking lines that make sense with one another. The plan may not be perfect but it does look very good.

Although I haven’t done an extensive survey of transit advocates in Austin, most of the talk I’ve seen about this plan has been extremely psyched. This isn’t just one expensive but low-ridership rail route for the point of having rail, but a system of interlocking lines that make sense with one another. The plan may not be perfect but it does look very good.

So why mention Cap Metro CEO Randy Clarke?

Astute observers may have noted a difference between my description of the Project Connect system and the map they released: I referred to three lines as being designated for light rail, whereas the Project Connect map refers to them as being “high ridership and cost.” Project Connect staff had mapped what mode (i.e. bus vs rail) makes sense for each corridor but CapMetro CEO Randy Clarke asked them to hold off on including it in their Phase Two report. Project Connect has set up Randy Clarke with a perfect softball pitch: come in to a new city and put a stamp on the most ambitious long-term plan to create a city with first-class transit. The question is: why is he not swinging?

Don’t gaslight us, Randy!

I’m still recovering from a bitter campaign on Austin’s last transit proposal, Proposition 1 in 2014. I rely on transit to get anywhere outside my immediate walking radius so it was extremely difficult to make my debut in local politics by opposing a major transit plan. But it was something I felt I had to do and to this day, I resent the fact that staff placed transit advocates in that position. It wasn’t just that most of the advocates had come to a different conclusion than the planners about route choices. I actually felt like through the course of the route selection process I was being gaslighted. I dug deeper into the 2014 route choice model than I ever wanted to. Every time I found a bizarre choice, I was told that no, the sky has always been red and it makes perfect sense to, say, assume students would be as likely to walk more than a mile from their home to a train station as they would be likely to walk half a mile. Or that it makes perfect sense to count potential homes as twice as important to ridership than actual existing homes.

When I look at this latest Project Connect map, I feel not only excitement for Austin’s future but a definite sense of relief and vindication for having argued that the sky was blue. Project Connect has confirmed that the non-professionals like myself who were skeptical of the 2014 process shared the same thought process with many professionals in the industry. That while some folks called myself and friends “transit trolls” and literally told us to “shut up” and listen to the experts, I wasn’t being naive to question, say, whether tunneling underneath the Hancock Center was really the best use of scarce transit funds. (It was then and remains a bad idea.) The conclusions that the professionals have drawn this time around are completely in line with the conclusions the amateur advocates drew last time and a fairly sharp repudiation of the 2014 proposal. But this sense of relief isn’t unlimited. The longer that any part of the Project Connect effort — staff or leadership — go without being willing to state obvious facts, the more that I worry that this effort, like the last one, will be derailed by bad choices.

Are autonomous vehicles the answer?

So reading Randy Clarke say things like: “We are not that far along from having maybe a (bus rapid transit) type of system that is autonomous, connected and electric that in a lot of ways may meet a lot of the desires and outcomes that modern-day (light rail transit) delivers because you may be able to connect two, three or four vehicles and separate them in a much different way, similar to how light rail system works today but with a lot less cost structure,” I get nervous.

Of course, driverless vehicles that connect multiple cars and carry a lot of people have existed for decades. Here’s one in Vancouver:

Driverless cars/autonomous vehicles in Vancouver already carry significant percentage of travelers around the city. pic.twitter.com/wvdxwHk86V

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) March 29, 2018

And if it’s true that radical new technologies change the cost equation at some point in the future then by all means nobody thinks we should ignore that. But for the sake of the collective sanity and confidence of Austin transportation advocates, Project Connect should come out and say “Barring anything paradigm-changing, these three routes are ripe for rail and the others should use some combination of enhanced bus measures.”

YIMBY is not left or right but both and neither

The YIMBY moment hasn’t exactly arrived in America but it’s on the platform and the train is coming. The framework for political arguments in many City Halls has transformed from “Neighborhood vs Developer” to “YIMBY vs NIMBY.” State Houses like California are being shaken up by YIMBY legislation, both passed and proposed.

The movement’s growth has created a scramble to define where it lies on the broader political spectrum. Various YIMBYs have staked a claim to be the true flagholders for popular local political labels, whether that be “progressive,” “free market,” or other. Opponents have been quick to identify YIMBYism with disliked groups in their local environments, whether that be United Nations Agenda 21 or the Koch brothers.

Now this is one hot take pic.twitter.com/vOIwuo3pBf

— Chandler Forsythe (@ctftx) February 21, 2018

Sorry, YIMBYs — the market won't save us. https://t.co/gp38wU6pqp

— Jacobin (@jacobinmag) August 8, 2017

This ideological mishmash is more than rhetoric. I correspond daily with (or twitter my life away, my wife would say) folks with radically different beliefs about economic systems who nevertheless work together toward a common goal of addressing the housing shortage. It doesn’t feel like an uncomfortable alliance of convenience, but rather a group of friends with different ideas. In a world where we’re constantly reminded of evergrowing ideological divides, how does this movement maintain this hodgepodge?

Jaap Weel gets to part of the answer here:

The ability to bridge ideological divides is a strength baked into the YIMBY movement from the start. We have @SonjaTrauss to thank for that, I think. You can't make a city affordable to more people without more homes in it, whether you're a liberal or a radical or whatever. https://t.co/TdAk5HLeey

— Coba Weel (@weel) January 8, 2018

YIMBYs believe places should accommodate as many of the people who want to live or work there as they can. This belief is so simple and the need so basic that it can fit into nearly any ideology. Indeed, human beings have been building and designing cities since millennia before Adam Smith or Karl Marx. Rather than saying that YIMBYism is socialist or capitalist, it’s more accurate to say that socialism and capitalism can be YIMBY or not.

Always blown away that Romans lived in 7-story apartment buildings 2000 years ago. https://t.co/FgyjVk7u2M pic.twitter.com/g0NAjKbti0

— Dan Keshet (@DanKeshet) February 8, 2018

A free market YIMBY platform could be “abolish height limits and developers will build more housing to meet market demand.” A socialist YIMBY platform could be “raise property taxes to build public housing.” An environmentalist YIMBY platform looks like SB827 while a social justice YIMBY platforms can focus on ending practices that exclude people from the best jobs or schools. All of these policies share the fundamental assessment that there aren’t enough homes (and/or workplaces, etc) and we need to build more of them, but they accomplish that goal through different mechanisms.

Many YIMBYs are inspired to ideas based on their previous ideas about economic systems (“cut regulations”, “community land ownership”, “better planning”). But further complicating the ideological picture, policies are often judged within YIMBY circles based on their ability to address the housing shortage and not necessarily based on ideological priors. It’s not uncommon to see the same person arguing for different solutions that could be glossed as “socialist”, “planned market”, or “free market.” Some ideas defy easy classification: for example, many YIMBYs believe that transit planning should be pushed to the local government level while land use planning should be pushed to higher levels of government. If you insist on looking at their ideas through a prism of capitalist vs socialist, this would be hopelessly confusing. But if you understand all of these as potential ways to get more people access to the places that they want, it makes sense.

So here’s a challenge: try to, instead of judging whether YIMBY as a whole is more an offshoot of one ideology or another, fully understand what problems it’s trying to solve and how you think those problems would best be solved.

6 things to like in California’s proposed transit housing law, illustrated by surfing

On January 4, California felt two earthquakes. The first was a conventional and thankfully weak earthquake in Berkeley:

The Did You Feel It? survey form for the Berkeley, CA M4.4 EQ is back up and running: https://t.co/jY2poBayEX Please tell us what you felt. pic.twitter.com/OVb8r4p22q

— USGS (@USGS) January 4, 2018

The second was a political earthquake, emanating from across the bay in San Francisco:

I’m introducing an aggressive housing legislative package: 1) require denser/taller zoning near public transit, 2) require cities’ housing goals be based on actual future growth & make up for past deficits, & 3) make it easier to build farmworker housing. https://t.co/YLQ9djH5pN

— Senator Scott Wiener (@Scott_Wiener) January 4, 2018

So, here are six things to like about the transit-oriented development bill that’s making waves in state politics:

1 It acknowledges the state has an interest in land use

Many decisions are better made by cities than states. Where will the next branch library go? Should this park have a splash pad or a lawn? But some problems are too big for one city alone, like intercity transportation. If Austin and San Antonio decide to be connected by a train, Buda, Kyle, San Marcos, or New Braunfels should have input (as the train would go through these cities), but they shouldn’t be given a flat veto. It is up to the state government to help manage this process so that local interests in one city don’t hurt local interests everywhere else.

In California and some other states, housing and land use have become problems with statewide and national implications. Housing prices aren’t just high in San Francisco or Los Angeles or even Berkeley; people unable to find housing in those cities are spilling over to suburbs and exurbs all across the state. Whole companies are looking to other states to set up offices because their workers can’t afford California rents. The greenhouse gases from long commutes affect every person on the planet. When a problem is widespread, the solution needs to be widespread too; cities rules by local interests just doesn’t cut it.

2 It creates fair and impartial rules

Laws made at the local level can take into account local context better than statewide rules can be. But laws made at the state level can better take into account the statewide context. In a drought, we need fair rules so that everybody does their part to conserve water and everybody has access to the water they need. In a statewide housing drought, we need fair rules so that everybody does their part to build housing.

3 It forges a link between transit and density

In the sphere of YIMBY and placemaking, the problem in California is a very YIMBYish problem: there aren’t enough homes to go around for all the people who want to live in California’s cities. But the solution that Wiener proposes isn’t just focused on getting people into homes anywhere. By proposing rules for allowing more homes near transit, it creates the chance for cities to use this as an opportunity to make great places for the future, where high-capacity transportation solutions are matched with high-capacity housing solutions.

4 It acknowledges how parking rules can hurt housing

One type of land use rule that’s particularly pernicious is the minimum parking regulation. These rules not only incentivize car use by forcing everybody to pay the price of car storage whether they drive or not, they also cut into the budget (both financially and physically) of new housing. This legislation will stop cities from using these pernicious rules near transit stops and opens the possibility for people to find new ways to live cheaper while using less parking.

5 It helps bridge the gap between people and jobs

The problems of California’s cities aren’t their problems alone. Vast swathes of the state are home to unique industries, from Silicon Valley’s tech economy to Hollywood’s movie industry. Sure, tech jobs exists outside Silicon Valley and movies are filmed all over the world. But place has, if anything, grown more important over the last decades, not less. Young workers looking to break into an industry would do well to show up where the jobs are, and new companies looking to start up would do well to show up where the workers are. Today, though, many people are shut out of these engines of prosperity because they can’t afford to live in Palo Alto, San Francisco, or Los Angeles while they lean the trade. Who knows what great technology or film talent we may cherish tomorrow if only we make room for them today?

6 It might just save humanity

With the United States federal government oriented away from action against climate change, individual states badly need to step up their game. While trying not to overstate the importance of this bill, the fate of the entire human race might depends on our ability to transition the United States and our high-emission society into one in which we can get around more efficiently.

So congratulations to Senator Scott Wiener! You brought a proposal that deals with the scale of the problems your state and this country are experiencing, and you may have changed the conversation on housing for good.

Words by Dan Keshet. Gif selection by Susan Somers.

Five Things to Like and Five to Improve for the North Shoal Creek Neighborhood Plan

Susan Somers is a north Austin resident near the North Shoal Creek area, President of urbanist organization AURA, and the genius gif editor who made this blog’s most famous piece pounce.

The city recently released a draft version of the North Shoal Creek Neighborhood Plan. North Shoal Creek is on the far edge of what you might consider north central Austin – bounded by Anderson Lane to the south, Highway 183 to the north, Mopac Boulevard to the west, and Burnet Road to the east. The plan is set to be the first new neighborhood plan in several years and City planning staff seem to have billed it as a kinder, gentler neighborhood plan: one that would try to fulfill the goals of Imagine Austin and identify new opportunities for growth. As such, the draft plan may give us a decent sense of what small area planning would look like if we continue churning out neighborhood plans in the CodeNEXT era.

How does the draft North Shoal Creek plan stack up?

Five things we like

- The plan acknowledges the reality that apartments are more affordable and single family homes are not. The plan repeatedly points out that the apartments and multifamily condominiums in the neighborhood are more affordable that the single family homes. What’s more, “Apartments and condominiums in North Shoal Creek provide more affordable options relative to much of Austin, while single-family homes are less affordable than the citywide average.” It also acknowledges that the majority of people in the planning area live not in the single family homes of the “Residential Core,” but in apartments along the edges of the neighborhood. Furthermore, it points out that the neighborhood’s residents are aging, and young families are being priced out.

- The plan prioritizes walkability. Almost half the “needs” and “values” identified by the community involved walkability in some way. The plan calls for new sidewalks and trails, better access to transit stops, and improved safety for schoolchildren walking to Pillow Elementary. It even contemplates innovative ideas such as opening up a pedestrian trail to access Anderson Lane businesses or allowing the community better access to Shoal Creek.

Hundreds of people live here, but this is not a place that invites walking. Image via Google Maps. - The plan allows homes on the neighborhood corridors. The plan acknowledges that retail, particularly along Burnet Road, is dying. It allows for mixed-use development including apartment homes to be built along Burnet Road and Anderson Lane, the neighborhood’s major corridors. It also acknowledges that transit access is a very important reason to allow these homes to be built, and that apartment density should be clustered near transit. While allowing apartments on transit corridors may seem obvious, North Shoal Creek has fought apartment homes in the past, so this is a promising development.

- The plan supports granny flats (aka “accessory dwelling units”). The plan seems to support allowing homeowners to build granny flats throughout the single family section of the neighborhood. Adding another home to a lot is an easy, almost invisible way to add more housing!

- The plan envisions an innovative “Buell District.” Buell Avenue is currently dotted with light industrial development like self-storage facilities and auto-repair shops. The plan envisions change along Buell Avenue, including special zoning opportunities like townhouses, small apartments, and live-work spaces that would allow a greater variety of housing into the neighborhood.

Five things to improve

- Choose some side streets for rowhouses. Other than on Buell Avenue, the plan does not call for allowing missing middle housing types like rowhouses on any side streets. We’ve previously argued rowhouses are an underappreciated and underused housing form in Austin, and CodeNEXT should allow more of them. But over and over again, our planning processes shy away from this awesome type of home. There are plenty of larger neighborhood streets in North Shoal Creek that would be appropriate for rowhouses. The plan leaves the impression that the only reason townhouses would be allowed on Buell is that the neighborhood likes the current light industrial businesses even less than they like rowhouses.

Rowhouses are a residential type of building and, as such, they belong every bit as much in residential-only areas as areas of mixed use. - Multiplexes or small apartments on corner lots. Similarly, other missing middle housing types like multiplexes, small apartments, or cottage courts, are not placed in the “Residential Core,” even on large corner lots. Large corner lots are the perfect place to allow this kind of missing middle.

This fourplex is one of the last standing of a formerly common missing middle housing type in residential Austin. - Sanctity of the “Residential Core.” Let’s talk more about that “Residential Core” phrase. As we note above, the plan acknowledges that the majority of residents live not in the interior of the neighborhood in single family homes, but in apartments on the edges of the neighborhood. Thus, calling the single family section of the neighborhood residential as compared to the corridors is a kind of double speak. Literally, more residents live outside the area termed “residential” in this plan! Based on the plan’s constraints, that pattern will become even more pronounced! Why does this terminology matter? Many other aspects of the plan focus strictly on the “Residential Core.” Three of the six bullet points regarding the goals of the Neighborhood Transition area focus not on making the zone great for its residents but on how not to encroach on the privacy of single family homes. The poorer majority residents are treated as interlopers on the richer minority. In fact, it’s not even clear that the existing apartments in the Neighborhood Transition lots would fit the constraints of the plan.

- Vision for connectivity/reconnecting streets. Residents in North Shoal Creek have asked for a more walkable neighborhood and for better access to transit stops. One way to make this area, designed with meandering streets and suburban cul-de-sacs, more walkable would be to designate opportunities to acquire lots and reconnect streets separating people from one another. While the plan considers this for connecting homes to retail via urban trails, there are no such connections proposed in the “Residential Core.”

Google Maps recommends a 17 minute walk along a freeway to walk between these backyard neighbors. - Tying desired neighborhood amenities (sidewalks, parks) to opportunities for density. There are many ambitious, desirable aspects of the plan that are unfunded mandates. These unfunded plans include building out the sidewalk network, adding urban trails, developing more parkland, and creating the Shoal Creek trail. The plan acknowledges the challenges of getting funding to make these a reality. But other neighborhoods where these improvements have actually taken place (like Bizarro Austin) have done more than make a wishlist and hope. They created incentives for redevelopment to happen and required developers to fund improvements to the public sphere as part of that redevelopment.

In some ways, the North Shoal Creek draft plan lives up to its kinder, gentler billing. It recognizes the real problems the neighborhood has: from families being priced out to unwalkability impinging on quality of life. The plan promotes the two main fixes we’ve also seen coming out of the latest draft of CodeNEXT: accessory dwelling units and apartment homes on transit corridors. Let us acknowledge that many of Austin’s older neighborhood plans don’t go even this far. However, to truly confront the problems the plan identifies, broader changes are needed, including in areas where the minority of neighborhood residents live. By opening up to a bit more change, some of the truly visionary elements of the plan could be funded and constructed.